China’s history is shaped by a succession of dynasties, each leaving a lasting impact on the nation’s culture, politics, and society. From the legendary Xia Dynasty to the fall of the Qing, these ruling houses defined different eras of Chinese civilization. Below is a timeline of Chinese dynasties, along with their approximate dates and key contributions:

Ancient and Early Dynasties (c. 2070–221 BCE)

Xia Dynasty (c. 2070–1600 BCE)

- The Xia Dynasty is often regarded as China’s first dynasty, marking the transition from prehistoric tribal communities to a more structured, state-like society. However, its existence remains a subject of debate among historians, as most records about the Xia come from much later historical texts, such as Sima Qian’s “Records of the Grand Historian”, rather than from direct archaeological evidence.

- According to traditional accounts, the Xia Dynasty was founded by Yu the Great, a legendary ruler credited with controlling the devastating Yellow River floods through an extensive system of dams and canals. His success in managing floods and irrigation is said to have established the foundation for early Chinese civilization. The Xia rulers developed hereditary rule, transitioning governance from tribal chieftains to a centralized monarchy.

- Although concrete evidence of the Xia Dynasty remains scarce, archaeologists have uncovered Bronze Age settlements, pottery, and early writing systems from the Erlitou culture (c. 1900–1500 BCE), which some scholars associate with the Xia Dynasty. These discoveries suggest that this period saw significant advancements in bronze metallurgy, social hierarchy, and early urbanization, paving the way for the more historically verifiable Shang Dynasty that followed.

Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE)

- The Shang Dynasty is widely recognized as the first historically confirmed Chinese dynasty, thanks to extensive archaeological evidence uncovered in modern times. It marked a significant transformation in Chinese civilization, introducing advancements in bronze casting, early writing, and urban development.

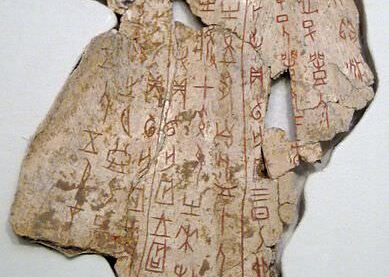

- One of the most remarkable contributions of the Shang Dynasty was the oracle bone script, an early form of Chinese writing. Inscribed on tortoise shells and animal bones, these inscriptions were used for divination, where rulers sought guidance from ancestors and deities. This writing system laid the foundation for classical Chinese characters.

- The Shang also excelled in bronze metallurgy, producing elaborate ritual vessels, weapons, and tools that demonstrated both artistic sophistication and technological innovation. The capital cities of the dynasty, such as Yin (modern-day Anyang), were well-organized urban centers with palaces, temples, and large defensive walls, indicating a high level of state control and military strength.

- The Shang rulers governed through a network of city-states, exerting influence over surrounding territories while maintaining a rigid social hierarchy. At the top was the king, who performed religious ceremonies to communicate with ancestors.

- The dynasty came to an end around 1046 BCE, when it was overthrown by the Zhou Dynasty after the Battle of Muye.

Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046–256 BCE)

- The Zhou Dynasty was the longest-lasting dynasty in Chinese history, spanning nearly eight centuries. It is traditionally divided into two major periods: the Western Zhou (1046–771 BCE) and the Eastern Zhou (770–256 BCE). This era was marked by political shifts, philosophical advancements, and cultural evolution that shaped the foundation of Chinese civilization.

- The Western Zhou period began after King Wu of Zhou overthrew the Shang Dynasty in the Battle of Muye. To justify their rule, the Zhou introduced the Mandate of Heaven, a political and spiritual doctrine stating that the legitimacy of a ruler was granted by divine forces. If a king failed to govern justly, he could lose this mandate, thus providing a moral framework for dynastic succession. During this period, the Zhou kings maintained control through a feudal system, granting land to noble families in exchange for loyalty and military service. This system allowed for relative political stability and economic growth, with advancements in agriculture, bronze casting, and early ironworking.

- The Eastern Zhou period began when the Zhou capital was relocated to Luoyang after being attacked by invading forces. This era was characterized by political fragmentation, as the once-unified kingdom splintered into competing states. It is further divided into two key sub-periods:

- Spring and Autumn Period (770–476 BCE): Named after the historical text Spring and Autumn Annals, this period saw increasing decentralization as local rulers fought for dominance. Small wars were frequent, but there were still periods of cultural and economic prosperity.

- Warring States Period (475–256 BCE): Marked by constant warfare between rival states, this period saw the rise of powerful military strategies, such as Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War”, and major advancements in governance, technology, and philosophy.

- Despite the chaos of the Eastern Zhou, it was one of the most intellectually significant periods in Chinese history. The instability and political strife led to the emergence of Confucianism, Daoism, and Legalism, three philosophies that would shape Chinese thought for centuries.

- By 256 BCE, the Zhou Dynasty had weakened to the point where it was little more than a symbolic authority. It was ultimately overthrown by the Qin, marking the rise of China’s first imperial dynasty.

Imperial Dynasties (221 BCE–220 CE)

Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE)

- The Qin Dynasty marked a turning point in Chinese history as it was the first time China was unified under a centralized imperial government. Founded by Qin Shi Huang, this short but highly influential dynasty laid the groundwork for the structure of Chinese governance for the next two millennia.

- Qin Shi Huang, the self-proclaimed First Emperor, abolished the feudal system and replaced it with a highly structured bureaucracy. He divided the empire into administrative units, appointing officials directly responsible to the central government, ensuring loyalty and efficiency.

- To unify his vast empire, Qin Shi Huang implemented sweeping reforms, including:

- Standardizing currency, weights, and measures to facilitate trade and economic integration.

- Creating a uniform writing system, ensuring effective communication across the empire. The Qin script became the foundation of modern Chinese characters.

- Expanding infrastructure, including building an extensive network of roads and canals to improve transportation and governance.

- Qin Shi Huang is perhaps best known for his ambitious construction projects:

- The Great Wall: To defend against northern invaders (particularly the Xiongnu), the emperor ordered the connection and expansion of existing defensive walls, forming the foundation of what would later become the Great Wall of China.

- The Terracotta Army: Discovered in 1974, this vast army of life-sized clay soldiers, chariots, and horses was built to guard Qin Shi Huang in the afterlife, reflecting the emperor’s desire for eternal power.

- The Qin Dynasty was heavily influenced by Legalist philosophy, which emphasized strict laws, absolute control, and severe punishments to maintain order. While these policies helped consolidate power, they also fostered widespread resentment. Qin Shi Huang suppressed opposition by burning Confucian texts and executing scholars, actions that later led to the dynasty’s downfall.

- Collapse of the Qin Dynasty

- Despite its achievements, the Qin Dynasty was short-lived. Qin Shi Huang’s sudden death in 210 BCE led to a power struggle, and his harsh policies triggered widespread revolts. By 206 BCE, rebel forces led by Liu Bang overthrew the Qin, paving the way for the rise of the Han Dynasty.

Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE)

- The Han Dynasty is often regarded as one of the greatest golden ages in Chinese history. Lasting over four centuries, it saw political stability, economic prosperity, military expansion, and remarkable advancements in science, technology, and culture. The influence of the Han was so profound that China’s dominant ethnic group still refers to itself as the “Han people.”

- After the fall of the Qin Dynasty, China was thrown into chaos until Liu Bang, a commoner-turned-general, defeated rival warlords and established the Han Dynasty in 206 BCE. He took the title Emperor Gaozu, moving away from the harsh Legalist rule of the Qin and incorporating elements of Confucianism into governance, which emphasized virtue, morality, and benevolent rule.

- The Han Dynasty is divided into two periods:

- Western Han (206 BCE–9 CE) – Capital at Chang’an; strong central rule, economic expansion.

- Eastern Han (25–220 CE) – Capital at Luoyang; revival after brief interruption, but eventual decline.

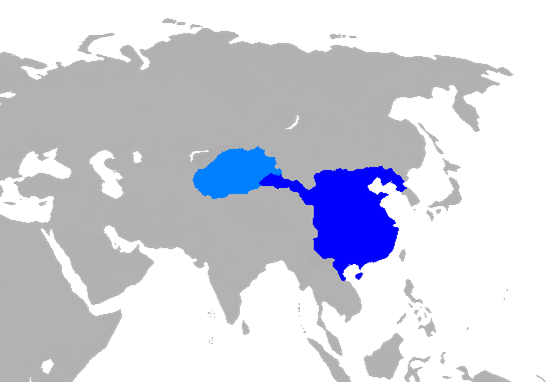

- One of the Han Dynasty’s most significant contributions was the development of the Silk Road, a vast network of trade routes connecting China to Central Asia, India, Persia, and the Roman Empire. The Silk Road facilitated trade, cultural exchange, and diplomatic relations, bringing silk, spices, paper, and other Chinese goods to distant lands, while also introducing foreign influences into China.

- To support economic growth, the Han government reformed taxation, improved agriculture, and monopolized industries like salt and iron. The introduction of the wheelbarrow, improved plows, and irrigation systems led to increased agricultural production, supporting a growing population.

- The Han Dynasty saw numerous breakthroughs in science, medicine, and technology, including:

- Invention of paper (c. 105 CE by Cai Lun), which revolutionized writing and record-keeping.

- Advances in astronomy, including the first star catalog and improved lunar calendars.

- Medical advancements, such as acupuncture and herbal medicine.

- Seismograph invention by Zhang Heng, used to detect earthquakes.

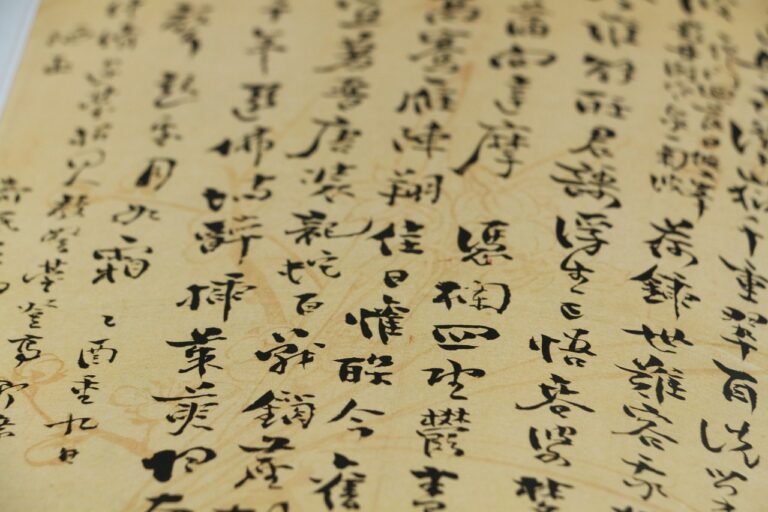

- Han literature and historical records flourished, with works like Sima Qian’s “Records of the Grand Historian” (Shiji), which became a model for Chinese historiography. Poetry, calligraphy, and painting also saw significant development.

- The Han Dynasty expanded its borders through military campaigns against the Xiongnu nomads in the north, Korea, Vietnam, and Central Asia. These conquests helped secure trade routes and increase China’s influence. The tribute system was established, strengthening diplomatic ties with neighboring states.

- By the late 2nd century CE, internal corruption, heavy taxation, peasant uprisings (such as the Yellow Turban Rebellion), and struggles between eunuchs and aristocrats weakened the dynasty. In 220 CE, the last Han emperor was overthrown.

Period of Division (220–589 CE)

Three Kingdoms (220–280 CE)

- The Three Kingdoms Period was one of the most turbulent yet fascinating eras in Chinese history, marked by constant warfare, political intrigue, and shifting alliances. Following the collapse of the Han Dynasty in 220 CE, China fragmented into three rival states—Wei, Shu, and Wu—each vying for supremacy. Though short-lived, this period left a lasting cultural impact, inspiring one of China’s most famous literary works, Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

Jin Dynasty (265–420 CE)

- The Jin Dynasty marked both the reunification of China after the chaotic Three Kingdoms Period and a later era of fragmentation. The dynasty is divided into two distinct phases:

- Western Jin (265–316 CE) – Founded by the Sima family, it briefly reunified China but was plagued by internal strife and invasions. The infamous War of the Eight Princes (291–306 CE) saw rival factions within the royal family fighting for control, weakening the empire. In 316 CE, nomadic Xiongnu-led forces sacked the capital Luoyang, marking the fall of the Western Jin.

- Eastern Jin (317–420 CE) – After the fall of the Western Jin, the ruling family fled south and established a government in Jiankang (modern-day Nanjing), ruling a fractured China. Although politically weak, the Eastern Jin saw cultural and economic prosperity, as many aristocrats and scholars fled south, bringing Confucian traditions, art, and literature.

Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589 CE)

- The Southern and Northern Dynasties period was marked by political fragmentation, cultural flourishing, and military conflict between the north and south.

- Northern Dynasties (386–581 CE): Rule by Non-Han States

- The north was ruled by various non-Han ethnic groups, including the Xianbei, who established powerful kingdoms such as the Northern Wei.

- The Northern Wei (386–534 CE) implemented Sinicization policies, adopting Han Chinese customs, Confucian governance, and Buddhism.

- After the fall of Northern Wei, the region was divided between the Eastern Wei, Western Wei, Northern Qi, and Northern Zhou, leading to continued warfare.

- Southern Dynasties (420–589 CE): Han Chinese Rule

- The south remained under Han Chinese rule, beginning with the Liu Song Dynasty (420–479 CE), followed by the Southern Qi, Liang, and Chen Dynasties.

- Southern China became a cultural and economic hub, preserving Confucian traditions and advancing literature, poetry, and calligraphy.

- The region was relatively weaker militarily, often struggling to defend against northern invasions.

Reunification and Flourishing (581–960 CE)

Sui Dynasty (581–618 CE)

- The Sui Dynasty was a brief but highly influential period in Chinese history, reunifying China after centuries of division and laying the groundwork for the powerful Tang Dynasty. Despite its short rule, the Sui implemented major reforms, strengthened central authority, and embarked on ambitious infrastructure projects, most notably the Grand Canal.

- The Sui reestablished a strong centralized government, promoting Confucian ideals, legalist policies, and bureaucratic efficiency.

- Strengthened the imperial examination system, ensuring government officials were selected based on merit rather than aristocratic birth.

- The failed invasions of Korea (612–614 CE) led to massive loss of life and public discontent.

Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE)

- The Tang Dynasty was one of China’s greatest imperial dynasties, ushering in a golden age of culture, economic prosperity, and territorial expansion. Often considered one of the most powerful and cosmopolitan empires in world history, the Tang saw major advancements in arts, literature, governance, and international trade.

- Founded by Emperor Gaozu (Li Yuan) in 618 CE, after overthrowing the declining Sui Dynasty. Expanded upon Sui administrative reforms, strengthening centralized rule and further developing the imperial examination system, which ensured merit-based government.

- The Tang era is known for its poetry, painting, music, and calligraphy, with poets like Li Bai, Du Fu, and Wang Wei producing some of China’s most famous literary works. Buddhism flourished, with monasteries playing key roles in education, charity, and diplomacy. Tang silk, ceramics, and artwork became highly valued across Asia, the Middle East, and even Europe.

- The Tang Dynasty revived and expanded the Silk Road, turning China into a major hub for international trade and diplomacy. Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an), the Tang capital, became one of the largest and most cosmopolitan cities in the world, hosting merchants, scholars, and diplomats from Persia, India, the Byzantine Empire, and the Arab world.

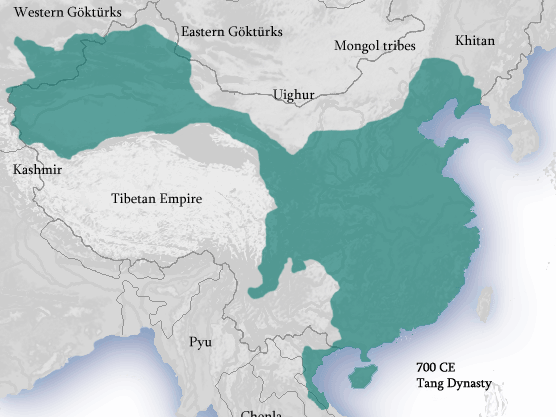

- The Tang expanded China’s borders into Central Asia, Tibet, Korea, and Vietnam, establishing a vast tributary system. The Battle of Talas (751 CE) against the Abbasid Caliphate marked the westernmost expansion of Chinese influence.

- The An Lushan Rebellion (755–763 CE) severely weakened the empire, leading to loss of central control and economic decline.

- Increasing corruption, military defeats, and regional uprisings further destabilized the dynasty.

- In 907 CE, the last Tang emperor was overthrown, leading to the chaotic Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period (907–960 CE).

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907–960 CE)

- The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period was a time of political fragmentation and warfare following the fall of the Tang Dynasty. Lasting for over half a century, it was characterized by rapidly changing dynasties in the north and multiple competing regional kingdoms in the south.

- In northern China, five successive short-lived dynasties controlled the imperial throne:

- Later Liang (907–923 CE) – Founded by Zhu Wen, a former Tang general who overthrew the last Tang emperor.

- Later Tang (923–936 CE) – Established by Li Cunxu, who claimed descent from the Tang royal family.

- Later Jin (936–947 CE) – Formed with support from the Khitan-led Liao Dynasty, but later became their vassal.

- Later Han (947–951 CE) – A brief dynasty that struggled to maintain power.

- Later Zhou (951–960 CE) – The last of the Five Dynasties, founded by Guo Wei, known for reform efforts.

- While the north saw dynastic changes, the south and southwest of China were divided into ten regional kingdoms, which remained relatively stable and prosperous:

- Yang Wu (907–937)

- Wuyue (907–978)

- Min (909–945)

- Ma Chu (907–951)

- Southern Han (917–971)

- Former Shu (907–925)

- Later Shu (934–965)

- Jingnan (924–963)

- Southern Tang (937–976)

- Northern Han (951–979)

Medieval and Late Imperial Periods (960–1912 CE)

Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE)

- The Song Dynasty was a pivotal era in Chinese history, marked by technological advancements, economic prosperity, and cultural achievements. It was divided into two distinct periods:

- Northern Song (960–1127 CE): The Song controlled a vast territory but faced constant threats from northern nomadic groups.

- Southern Song (1127–1279 CE): After losing northern China to the Jurchen-led Jin Dynasty, the Song court relocated south, where it continued to thrive economically and culturally.

- The Sui Dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu (Zhao Kuangyin), who reunified much of China after the chaos of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

- Implemented bureaucratic and tax reforms, leading to a highly organized state.

- Faced ongoing military pressure from nomadic groups like the Khitan (Liao Dynasty), Jurchen (Jin Dynasty), and Mongols.

- Movable-type printing revolutionized book production, making knowledge more accessible. Gunpowder weapons emerged, changing the nature of warfare. Also, advanced shipbuilding and navigation technologies, including the magnetic compass, strengthened maritime trade.

- Expansion of rice cultivation in southern China led to a population boom, making China the most populous country in the world at the time.

- Development of paper money (banknotes) and a thriving commercial economy facilitated trade both domestically and internationally.

- The Song Dynasty was a golden age of landscape painting, with artists like Fan Kuan and Guo Xi.

- Poetry and literature flourished, with scholars such as Su Shi (Su Dongpo) making significant contributions.

- Neo-Confucianism, led by philosophers like Zhu Xi, became the dominant intellectual movement, blending Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist thought.

- The Northern Song fell in 1127 CE when the Jin Dynasty captured Kaifeng, forcing the court to relocate south. The Southern Song maintained resistance against northern invaders for over a century but ultimately fell to the Mongol Empire in 1279 CE, when Kublai Khan established the Yuan Dynasty.

Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 CE)

- The Yuan Dynasty was founded by Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, marking the first time the whole China was ruled by a non-Han dynasty. This period saw the integration of Mongol governance with Chinese traditions, increased international trade, and cultural exchanges along the Silk Road.

- The Mongols implemented a four-tiered class system, with Mongols at the top, followed by Central Asians, Northern Chinese, and Southern Chinese at the bottom. This system created ethnic tensions between the rulers and the Han majority.

- Marco Polo, the Venetian traveler, visited China and described the wealth and grandeur of Kublai Khan’s court in his famous book, sparking European interest in the East.

- The Yuan Dynasty promoted religious tolerance, allowing the practice of Buddhism, Daoism, Islam, and Christianity.

- Advances in printing, astronomy, and medicine continued, with influences from Persian and Central Asian scholars.

- Frequent natural disasters (such as floods and droughts) led to widespread famine and peasant uprisings.

- The Red Turban Rebellion (1351–1368 CE), led by Han Chinese rebels, contributed to the downfall of the Yuan Dynasty.

- In 1368 CE, the Yuan were overthrown by Zhu Yuanzhang, who established the Ming Dynasty.

Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 CE)

- The Ming Dynasty was a time of political stability, economic prosperity, and cultural brilliance. It marked the restoration of Han Chinese rule after nearly a century of Mongol dominance under the Yuan Dynasty. The Ming emperors focused on revitalizing Chinese traditions, strengthening the Great Wall, and expanding maritime exploration.

- Founded by Zhu Yuanzhang (Emperor Hongwu) in 1368 CE, who led the Red Turban Rebellion to overthrow the Mongols.

- The Ming emperors centralized power, reducing the influence of powerful court officials and reinforcing the Confucian bureaucracy.

- The capital was initially Nanjing, but later moved to Beijing by Emperor Yongle (1402–1424 CE).

- Under Emperor Yongle, the Ming sponsored Zheng He’s legendary voyages (1405–1433 CE), reaching as far as Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East, and East Africa.

- The tribute system was expanded, strengthening China’s influence over neighboring states.

- The Ming economy thrived due to agricultural advancements, urbanization, and a booming trade network.

- Chinese ceramics, particularly blue-and-white porcelain, became highly sought after worldwide.

- Literature and arts flourished, with the emergence of famous works such as Journey to the West, The Water Margin, and The Plum in the Golden Vase.

- The Forbidden City was constructed as the imperial palace in Beijing, symbolizing the grandeur and authority of the Ming emperors.

- Corruption, weak leadership, and economic decline plagued the later Ming years.

- In 1644 CE, the Ming capital, Beijing, fell to rebel forces, and the Manchus seized the opportunity to establish the Qing Dynasty, marking the end of Ming rule.

Qing Dynasty (1644–1912 CE)

- The Qing Dynasty, founded by the Manchus, was China’s last imperial dynasty.

- Early Qing rulers, such as Emperor Kangxi (r. 1661–1722 CE) and Emperor Qianlong (r. 1735–1796 CE), expanded China’s territory to its greatest extent, incorporating Tibet, Xinjiang, Mongolia, and Taiwan.

- The Qing maintained Confucian bureaucracy and Chinese traditions while enforcing Manchu customs, such as the queue hairstyle for men.

- The Qing period saw agricultural expansion and population growth, with China’s population surpassing 400 million by the 19th century.

- Trade flourished, especially in silk, tea, and porcelain, with European merchants seeking Chinese goods.

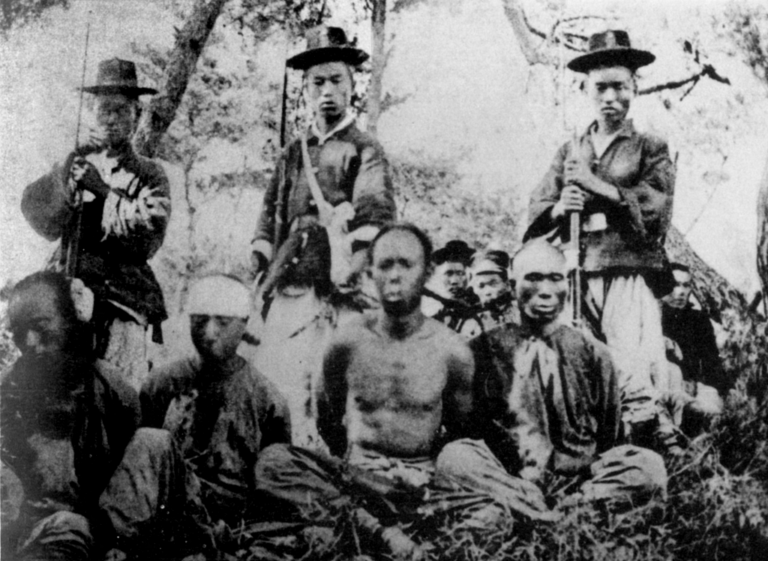

- The White Lotus Rebellion (1796–1804 CE) and the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864 CE) weakened Qing rule. The Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901 CE) reflected growing resentment toward foreign influence.

- The Opium Wars (1839–1842, 1856–1860 CE) led to humiliating defeats against Britain and forced China to sign unequal treaties, including the Treaty of Nanjing (1842 CE), which ceded Hong Kong to Britain.

- The Self-Strengthening Movement (1861–1895 CE) attempted to modernize China but failed due to resistance from conservative officials. Similarly, the Hundred Days’ Reform (1898 CE), led by Emperor Guangxu, was quickly suppressed by the powerful Empress Dowager Cixi.

- Growing nationalist movements, including the Revolutionary Alliance led by Sun Yat-sen, sought to overthrow the Qing. The Xinhai Revolution (1911 CE) led to the abdication of Emperor Puyi in 1912 CE, officially ending over 2,000 years of imperial rule.

Modern Era (1912–present)

Republic of China (1912–1949)

- The Xinhai Revolution (1911), led by Sun Yat-sen and other revolutionary figures, resulted in the abdication of Emperor Puyi and the creation of the Republic of China in 1912.

- The early years of the Republic were filled with political turmoil, foreign aggression, and internal conflict, making it a period of immense change and struggle for national unity.

- Sun Yat-sen became the first provisional president, advocating for three principles of the people: nationalism, democracy, and the people’s livelihood. However, Sun’s government was weak and lacked real control over China, which was still fragmented due to the presence of powerful warlords in various regions.

- After the death of Yuan Shikai, the first official president of the Republic, in 1916, China fell into a period of fragmentation known as the Warlord Era. During this period, various military leaders (warlords) controlled different parts of China, and central government authority was almost nonexistent.

- The rivalry between the Kuomintang (KMT), led by Chiang Kai-shek, and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), led by Mao Zedong, intensified during the 1920s and 1930s.

- Japan’s growing imperial ambitions in the 1930s led to the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945).

- The Japanese occupation of large parts of China, including the devastating Nanjing Massacre, resulted in widespread death, destruction, and suffering for the Chinese people.

- Despite the occupation, China remained unified in its resistance to Japan, with both the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) under Chiang Kai-shek and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) under Mao Zedong collaborating in the war effort against the Japanese. After Japan’s defeat in 1945, the civil war between the KMT and the CCP resumed.

- In 1949, after years of fighting, the CCP emerged victorious, and Mao Zedong declared the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on October 1, 1949, marking the end of the Republic of China.

People’s Republic of China (1949–Present)

- On October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong declared the founding of the People’s Republic of China in Tiananmen Square, marking the culmination of the Chinese Revolution.

- Mao and the CCP sought to implement Marxist-Leninist principles and establish a socialist state that would address the historical injustices and inequality faced by the Chinese people.

- Mao Zedong’s leadership was defined by a series of ambitious but often disastrous campaigns aimed at transforming Chinese society. The Great Leap Forward (1958–1962), an effort to rapidly industrialize China and collectivize agriculture, resulted in widespread famine, causing millions of deaths and severe economic disruption. The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), another Maoist campaign, sought to purify Chinese society by attacking perceived capitalist and traditional elements, leading to social chaos, the persecution of intellectuals, and the destruction of cultural heritage.

- After Mao’s death in 1976, China entered a period of political and economic transition. Deng Xiaoping emerged as China’s paramount leader, ushering in a new era of economic reform and opening up to the world.

- In 1978, Deng introduced the “Reform and Opening Up” policies, shifting China from a centrally planned economy to a market-oriented economy. These reforms allowed for private enterprise, opened the country to foreign investment, and led to the creation of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in cities like Shenzhen.

- As China’s economy grew, so did its global influence. The 1990s and 2000s saw China become a key player on the world stage, joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 and increasing its economic and political engagement globally.

…

Related articles:

Education System during the Han Dynasty

The Song Dynasty: A Civilization Far Ahead of Its Time