Italy’s history is a rich tapestry woven from the threads of ancient civilizations, transformative states, and dynamic cultural evolutions. Below is an overview of the major periods in Italy’s history, highlighting key events and developments that shaped the region.

1. Prehistoric and Ancient Italy (before 800 BCE)

- Prehistoric Period: Archaeological evidence suggests human presence in Italy as early as the Paleolithic period, with notable sites such as the caves of Altamura. The Neolithic period saw the rise of agricultural societies and the construction of settlements like Matera.

- Bronze and Iron Ages: During these eras, Italy was home to the Apennine and Villanovan cultures. Trade flourished, particularly with the Aegean world. The rise of proto-urban centers laid the groundwork for later city-states.

2. Etruscan and Early Italic Civilizations (c. 800–509 BCE)

- Etruscans: Flourishing in central Italy, the Etruscans established a sophisticated civilization known for its art, metallurgy, and urban planning. They significantly influenced Roman culture, especially in religion and governance.

- Italic Tribes: In southern and central Italy, tribes like the Latins, Samnites, and Umbrians began forming distinct cultural and political identities. Greek colonists established cities such as Naples and Syracuse in the south, creating a region known as Magna Graecia.

3. Roman Republic (509–27 BCE)

- Foundation of the Republic: In 509 BCE, the Romans overthrew the Etruscan monarchy and established a republican form of government. The Republic was governed by elected magistrates, a Senate, and popular assemblies, creating a system of checks and balances that influenced future democratic systems.

- Codification of Law: The Twelve Tables, established in the mid-5th century BCE, formed the foundation of Roman law, ensuring greater equality among citizens and shaping legal principles that persist today.

- Expansion Across Italy: Through strategic alliances, treaties, and military campaigns, Rome gradually unified the Italian peninsula. The conquest of the Samnites, Etruscans, and Greek colonies in Magna Graecia by the 3rd century BCE was critical in securing Roman dominance.

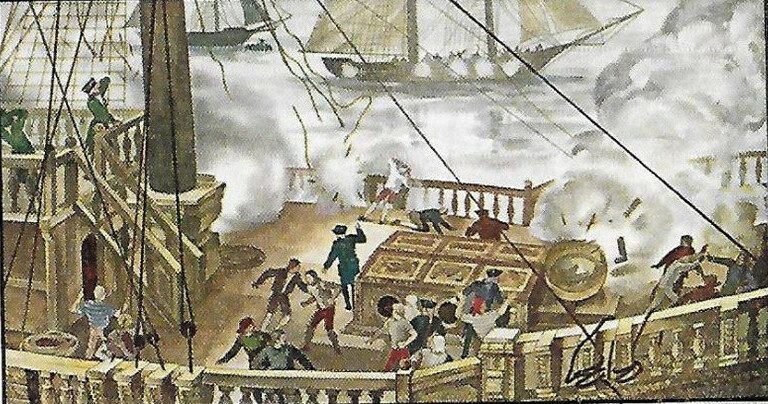

- Military Prowess: The Roman legions, characterized by discipline and adaptability, became a formidable force. Key victories in wars like the Punic Wars against Carthage allowed Rome to expand beyond Italy, acquiring territories in Spain, North Africa, and the eastern Mediterranean.

- Internal Struggles: Social and political tensions arose between the patricians (aristocratic elites) and plebeians (commoners), leading to the Conflict of the Orders. This struggle resulted in the plebeians gaining more rights, including access to political offices and protection through the Tribunes of the Plebs.

- Economic and Cultural Flourishing: Rome’s expansion brought immense wealth, fueling construction projects like roads, aqueducts, and temples. Roman culture began integrating Greek art, philosophy, and literature, which heavily influenced the development of Roman identity.

- End of the Republic: By the late Republic, internal turmoil, including class struggles and power grabs by influential generals like Julius Caesar, led to the Republic’s decline. Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE and subsequent civil wars paved the way for Augustus to become Rome’s first emperor in 27 BCE.

4. Imperial Rome (27 BCE–476 CE)

- Principate Period (27 BCE–235 CE)

- The Augustan Age (27 BCE–14 CE): Augustus, Rome’s first emperor, ushered in the Pax Romana (“Roman Peace”), a period of stability and prosperity. Reforms in administration, taxation, and infrastructure solidified Rome’s power. Augustus also encouraged cultural revival, supporting poets like Virgil and Horace.

- Julio-Claudian Dynasty (14–68 CE): A line of emperors descended from Augustus, including Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero. Rome expands to Britain under Claudius but sees internal instability under Nero.

- Year of the Four Emperors (69 CE): A brief civil war following Nero’s death, leading to the rise of the Flavian Dynasty.

- Flavian Dynasty (69–96 CE): Stability restored under emperors Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian. Key achievements include the completion of the Colosseum.

- Adoptive Emperors (96–180 CE): Also known as the “Five Good Emperors” (Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius), this era is marked by prosperity, territorial expansion, and cultural flourishing. The empire reaches its maximum territorial extent under Trajan.

- Commodus and Decline (180–235 CE): Commodus’ reign marks the end of the Pax Romana, leading to a period of instability and weakened leadership.

- Crisis of the Third Century (235–284 CE)

- A turbulent period with over 20 emperors in 50 years, marked by political instability, economic decline, and external invasions by Germanic tribes and Persian forces.

- The empire nearly collapses but is stabilized by Emperor Aurelian, who strengthens borders and reclaims lost territories.

- Dominate Period (284–476 CE)

- Diocletian’s Reforms (284–305 CE):

- Establishment of the Tetrarchy (rule of four) to improve governance by dividing the empire into eastern and western halves.

- Reorganization of administration, taxation, and military defenses.

- Constantinian Era (306–337 CE):

- Constantine the Great reunites the empire, establishes Constantinople as the new eastern capital, and promotes Christianity.

- The Edict of Milan (313 CE) grants religious tolerance.

- Later 4th Century (337–395 CE):

- Increasing division between the Eastern and Western Roman Empires.

- Barbarian incursions intensify, with the Visigoths defeating Roman forces at the Battle of Adrianople (378 CE).

- Final Decline of the West (395–476 CE):

- Theodosius I officially splits the empire upon his death (395 CE).

- Invasions by Huns, Vandals, and Ostrogoths weaken the western provinces.

- The sack of Rome by the Visigoths (410 CE) and Vandals (455 CE) symbolizes the empire’s vulnerability.

- The Western Roman Empire falls in 476 CE when Romulus Augustulus is deposed by Odoacer, while the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) continues for another millennium.

5. Early Medieval Italy (476–1000 CE)

- Ostrogothic Kingdom (493–553 CE): Following Rome’s collapse, the Ostrogoths, led by Theodoric the Great, established a kingdom centered in Italy.

- Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna (554–751 CE):

- After Justinian’s conquest, Italy became a fragmented province of the Byzantine Empire.

- The Exarchate of Ravenna governed Byzantine territories, but its control was weak and decentralized.

- Lombard Invasion (568 CE): The Lombards, a Germanic tribe, invaded northern and central Italy, establishing the Lombard Kingdom with its capital at Pavia.The Lombards challenged Byzantine authority, reducing its holdings to regions like Ravenna, Rome, and southern Italy.

- Charlemagne’s Conquest (774 CE):

- The Frankish King Charlemagne defeated the Lombards and declared himself King of the Lombards, integrating northern Italy into his empire.

- Charlemagne’s rule was marked by the spread of Carolingian reforms, including administrative organization and church patronage.

- Rise of the Papal States (8th Century):

- The Papacy gained temporal authority over central Italy, supported by the Donation of Pepin (756 CE), which granted lands to the Pope.

- Rome became a spiritual and political center, laying the groundwork for the Papal States’ emergence.

- Saracen and Magyar Raids (9th–10th Centuries)

- Saracen Invasions: Muslim Saracen pirates raided and settled parts of southern Italy, including Sicily (occupied from 827 CE) and coastal areas. Cities like Bari became Saracen strongholds until they were retaken by Christian forces.

- Magyar Threats: The Magyar (Hungarian) incursions targeted northern Italy in the 9th and 10th centuries, further destabilizing the region.

- The Holy Roman Empire and Feudal Italy (962–1000 CE)

- Otto I’s Coronation (962 CE): Otto I, King of Germany, was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by the Pope in 962 CE, marking the integration of Italy into the Holy Roman Empire.Northern Italy became a key territory within the empire, though imperial control often faced resistance from local powers.

6. Late Medieval and Renaissance Italy (1000–1500 CE)

- Early Communes and Feudal Struggles (1000–1200 CE)

- Feudal Legacy and Urban Growth:

- Italy’s regions began transitioning from feudal rule to urban independence.

- Many towns in northern and central Italy developed into communes, self-governing entities led by councils of local elites.

- Conflict with the Holy Roman Empire:

- The Investiture Controversy (1075–1122) between the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire affected Italy, with local rulers aligning with either the Guelphs (papal supporters) or Ghibellines (imperial supporters).

- Feudal Legacy and Urban Growth:

- Rise of City-States and Regional Powers (1200–1350 CE)

- Key city-states like Florence, Venice, Milan, Genoa, and Pisa gained prominence, competing for economic and political supremacy.Wealthy merchant families, such as the Medici in Florence, played critical roles in shaping these cities.

- Renaissance (14th–16th centuries): Italy was the birthplace of the Renaissance, a cultural rebirth characterized by advancements in art, science, and philosophy. Figures like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Machiavelli left an enduring legacy.

7. Early Modern Italy (1500–1815)

- Foreign Dominance: Italy became a battleground for European powers, with Spain, France, and Austria controlling various regions.

- The Italian Wars (1494–1559):

- A series of conflicts among France, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire for control of Italy.

- Key events include Charles VIII of France’s invasion in 1494 and the Sack of Rome (1527) by imperial troops, symbolizing Italy’s vulnerability.

- Spanish Habsburg Domination (1559–1713)

- Italy became a patchwork of territories under Spanish control or influence. Key regions included:

- The Kingdom of Naples and Sicily, ruled directly by Spain.

- The Duchy of Milan, a strategic northern territory.

- The Papal States, maintaining nominal independence but influenced by Spain.

- The Republics of Venice and Genoa, which retained autonomy but were economically constrained.

- Italy became a patchwork of territories under Spanish control or influence. Key regions included:

- Austrian Habsburg Period and Enlightenment Influence (1713–1796)

- War of Spanish Succession (1701–1714):

- The Treaty of Utrecht (1713) ended Spanish Habsburg rule in Italy, transferring significant territories to the Austrian Habsburgs.

- Italian intellectuals embraced Enlightenment ideals, advocating for reform in governance, education, and economics.

- Napoleonic Era (1796–1815)

- French Revolutionary Wars (1796–1799):

- Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaigns in Italy dismantled the old feudal and monarchical systems.

- The Cisalpine Republic (northern Italy) and Roman Republic (central Italy) were established as French client states.

- Napoleonic Kingdoms (1805–1815):

- The Kingdom of Italy, with Napoleon as its ruler, encompassed northern Italy, while southern Italy became the Kingdom of Naples, ruled by Napoleon’s relatives or generals.

- Reforms under Napoleon: Napoleon introduced modern legal and administrative systems, including the Napoleonic Code, which restructured governance and property laws.

8. Unification and Modern Italy (1815–Present)

- Post-Napoleonic Restoration (1815–1848)

- Congress of Vienna (1815):

- Italy was fragmented into various states under Austrian influence or local monarchies:

- Lombardy-Venetia became part of the Austrian Empire.

- The Papal States returned to papal control.

- The Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont (including Savoy and Nice) was restored to the House of Savoy.

- The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was ruled by the Bourbon dynasty.

- The Risorgimento and Italian Unification (1848–1871)

- Revolutions of 1848:

- A wave of revolutions across Europe sparked uprisings in Italy, particularly in Milan, Venice, and Rome.

- Although these were suppressed, they highlighted the demand for independence and constitutional rule.

- Role of Piedmont-Sardinia (1848–1861):

- The Kingdom of Sardinia, under King Victor Emmanuel II and Prime Minister Count Camillo di Cavour, became the leader of the unification movement.

- Key milestones included:

- Second Italian War of Independence (1859): Alliance with France (Napoleon III) helped defeat Austria, leading to the annexation of Lombardy.

- Expedition of the Thousand (1860): Giuseppe Garibaldi’s campaign liberated Sicily and southern Italy, unifying them with the north.

- Proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy (1861):

- Victor Emmanuel II was declared the first king of a united Italy, although Venice and Rome were not yet part of the kingdom.

- Liberal Italy and Challenges of Nation-Building (1871–1922)

- Economic and Social Struggles: Widespread poverty and regional disparities between the industrialized north and the agrarian south (known as the Southern Question). Mass emigration to the Americas and Europe as millions of Italians sought better opportunities.

- Fascist Era and World War II (1922–1945)

- Rise of Fascism (1922):

- Benito Mussolini seized power through the March on Rome and established a totalitarian regime.

- Fascist policies emphasized nationalism, militarism, and corporatism, suppressing opposition.

- Aggressive Expansion:

- Mussolini’s ambitions led to conflicts in Ethiopia (1935–1936) and an alliance with Nazi Germany, forming the Axis Powers.

- World War II (1939–1945):

- Italy initially achieved some territorial gains but suffered defeats, leading to Mussolini’s downfall in 1943.

- Republican Italy and Reconstruction

- Abolition of the Monarchy (1946):

- Following a referendum, Italy became a republic, and King Umberto II went into exile. A new constitution was adopted in 1948, establishing a parliamentary democracy.