The history of France is deeply intertwined with its Roman past, as the region of Gaul was one of the most significant territories in the Roman Empire for over five centuries. The Roman presence in Gaul, from its initial conquest in 121 BCE to the eventual fall of Roman authority in the late 5th century CE, profoundly shaped the culture, infrastructure, and political landscape of modern-day France.

Roman Conquest and Integration (until 50 CE)

Pre-Roman Influence in Gaul (Before 121 BCE)

The Romans first came into contact with the region that would later become known as Roman Gaul during the Roman Republic, as their influence spread across the Mediterranean world. By the mid-2nd century BCE, Roman trade and diplomatic relations had extended into southern Gaul, particularly with the Greek colony of Massilia (modern-day Marseille). This coastal city, founded around 600 BCE by Greek settlers, was an important commercial hub.

During this time, the Romans established an alliance with the Massiliotes, agreeing to protect the city from local Gallic tribes, especially the Aquitani, who lived to the west, and the Carthaginians who might threaten their Mediterranean interests. In return, Massilia provided Rome with land that was vital for the construction of a military road connecting southern Gaul with Hispania (modern Spain). This route, which became crucial for the movement of Roman legions, facilitated Rome’s expanding influence in the western Mediterranean and its eventual conquest of the Iberian Peninsula.

Rome’s First Footsteps in Gaul (122 BCE)

In 122 BCE, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, a Roman general, launched a military campaign against the Allobroges, a Gallic tribe in southern Gaul. His victory over the Allobroges was a significant early step in Rome’s eventual military involvement in Gaul, as it solidified Roman control over the region and established Rome’s presence in the area. Shortly after, in 121 BCE, Quintus Fabius Maximus led a campaign against the Arverni, one of the most powerful Gallic tribes. Under the leadership of King Bituitus, the Arverni were defeated, further extending Roman influence into the heart of Gaul.

In 121 BCE, the Romans defeated the Celtic tribes of southern Gaul and established the province of Gallia Narbonensis (modern Provence). This secured an essential Mediterranean coastline and a strategic route to Rome’s Spanish provinces. Over time, Roman influence expanded beyond military control, as trade and cultural exchanges with local tribes increased.

Julius Caesar and the Gallic Wars (58–50 BCE)

The decisive phase of Roman conquest came with Julius Caesar’s campaigns from 58 BCE to 50 BCE. These wars, famously chronicled in Caesar’s Commentarii de Bello Gallico, marked the transition from Roman military expeditions to full-scale imperial control. Caesar’s campaigns targeted major Gallic tribes such as the Helvetii, Arverni, and Belgae, with the goal of solidifying Rome’s power in Gaul. Through strategic alliances and military victories, Caesar extended Roman influence into the heart of Gaul, winning battles such as the Battle of Bibracte (58 BCE) and the Battle of Gergovia (52 BCE).

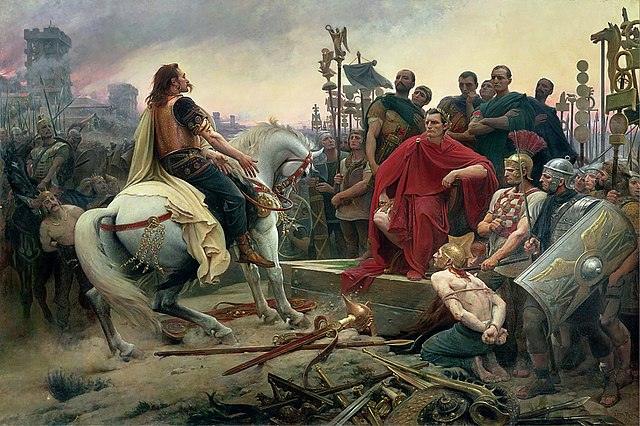

The Siege of Alesia and the Fall of Vercingetorix (52 BCE)

The siege of Alesia is widely regarded as the most significant event in the Roman conquest of Gaul. In 52 BCE, Vercingetorix, the leader of the united Gallic tribes, made a final stand at Alesia, a hilltop fortress. Despite desperate efforts to break the Roman siege lines, the Gauls were surrounded, and Vercingetorix surrendered to Caesar, marking the collapse of Gallic resistance. This victory allowed Caesar to claim unchallenged control over Gaul.

Early Roman Administration and Integration (50 BCE – 50 CE)

Following the conquest, Rome began the slow process of integrating Gaul into the empire’s vast administrative system.

During Caesar’s civil war (49 BCE), the Greek colony of Massilia (modern Marseille) sided with Pompey against Caesar. As a result, it was besieged and defeated in 49 BCE. Though the city was allowed to retain nominal autonomy, it lost much of its influence and land, marking a significant shift in regional power dynamics.

In 43 BCE, the city of Lugdunum (modern Lyon) was founded and quickly developed into the administrative center of Gaul. Its strategic location along key trade routes made it a hub of commerce and governance, reinforcing Roman authority in the region.

Formal provincial administration was only fully established during the reign of Augustus in 27 BCE. Gaul was reorganized into multiple provinces, including Gallia Lugdunensis, Gallia Belgica, and Gallia Aquitania, ensuring efficient governance. Parts of eastern Gaul were later incorporated into Raetia (15 BCE) and Germania Superior (AD 83).

- Gallia Lugdunensis (centered around the city of Lugdunum, modern-day Lyon) became the administrative hub of Roman Gaul.

- Gallia Belgica (northern Gaul) was populated by the Belgic tribes and served as a key region for trade with Germanic territories.

- Aquitania (southwestern Gaul) was characterized by its natural resources and agricultural output.

The Romans organized the vast territories of the provinces of Gaul into civitates, administrative districts that largely corresponded to the pre-conquest communities, often referred to as “tribes.” These included groups such as the Aedui, Allobroges, Bellovaci, and Sequani. While the civitates served as essential governing units, they were often too large for effective administration, leading to further subdivisions into pagi.

The Romans incorporated this system into their broader imperial framework, using civitates as the foundation for local governance. Over time, these administrative districts also became the basis for ecclesiastical bishoprics and dioceses, shaping the territorial organization of medieval France.

Pax Romana in Gaul (50 CE – 200 CE)

Urbanization and Romanization of Gaul

One of the most visible changes in Gaul during this period was the rapid urbanization of the region. The Romans constructed cities and towns, many of which became thriving hubs of commerce, culture, and politics. Roman cities were carefully planned with wide streets, forums (public squares), temples, baths, amphitheaters, and theaters.

The city of Lugdunum (modern-day Lyon) was established as the principal administrative and commercial center of Roman Gaul. It quickly grew in importance, becoming the capital of Gallia Lugdunensis. Its central location along major trade routes allowed it to flourish as a major economic hub for the entire Roman Empire.

Other cities, such as Augustodunum (Autun), Mediolanum Santonum (Saintes), and Lutetia (Paris), grew from modest settlements into thriving urban centers, complete with forums, baths, and amphitheaters. These cities were linked by an extensive road system, including the Via Agrippa, which stretched from Lyon to the Atlantic coast, enhancing connectivity and commerce across Gaul.

In addition to urbanization, Romanization—the spread of Roman culture, language, and customs—was evident across the region. The Latin language began to replace the native Celtic languages, and Roman architectural styles, religious practices, and legal norms were adopted by local inhabitants. Over time, the influence of Roman law, the Roman pantheon of gods, and Roman engineering began to permeate everyday life in Gaul.

Economic Prosperity

Agriculture was the backbone of the economy in Roman France. The fertile lands of Gallia allowed for the cultivation of wheat, barley, oats, grapes, and olives. Large villas, or rural estates, dominated the countryside, producing surplus food for local consumption and export. Roman techniques such as improved plowing methods and crop rotation helped increase productivity.

Viticulture (wine production) flourished, especially in regions like Bordeaux and Champagne, where the Romans introduced advanced winemaking techniques. Gaul’s vineyards provided quality wine that was exported throughout the Roman world. Wheat also became a significant agricultural product, helping to feed the growing Roman population, particularly in Rome itself.

Gallia was rich in natural resources, particularly iron, lead, copper, and silver. Roman authorities organized large-scale mining operations, with significant centers in areas such as the Massif Central and the Pyrenees. These metals were essential for coin production, weapons, and tools.

Trade flourished in Roman France due to well-established road networks and navigable rivers. The Roman road system, including the Via Domitia and Via Agrippa, connected Gallia with the rest of the empire, facilitating the movement of goods and people. Ports such as Massilia (modern-day Marseille) served as key hubs for Mediterranean trade, linking Gallia with Italy, North Africa, and the eastern provinces. Merchants traded a variety of goods, including pottery, textiles, metalwork, and luxury items like glassware and jewelry. The presence of Roman coinage standardized transactions, making trade more efficient. Markets and forums in urban centers such as Lugdunum (Lyon) and Burdigala (Bordeaux) thrived with local and imported goods.

The Role of Emperor Claudius

Emperor Claudius, who ruled from 41 CE to 54 CE, played a crucial role in the integration of Gaul into the Roman Empire. He was born in Gaul, in the city of Lugdunum, which gave him a unique connection to the region. As emperor, Claudius encouraged the inclusion of Gauls into the Roman Senate, and in 48 CE, he extended the privilege of Roman citizenship to many Gallic elites, allowing them to hold important political positions within the empire. This solidified the bond between Gaul and the broader Roman Empire, signaling that Gaul was no longer a conquered territory, but a full-fledged part of the empire.

The Role of Emperor Caracalla

Born in Lugdunum, Caracalla (188–217 CE) is best known for the Constitutio Antoniniana, which granted Roman citizenship to nearly all free inhabitants of the empire. This decree had a profound economic and social impact on Gallia, further integrating it into the Roman world. In addition to this policy, Caracalla is also remembered for his ambitious construction projects, such as the Baths of Caracalla in Rome, which became one of the largest and most luxurious bath complexes of the ancient world. His military campaigns, particularly along the Germanic frontier, aimed to secure and expand Rome’s northern borders, ensuring the continued stability of Gallia and other frontier provinces. However, his rule was marked by brutality and heavy taxation, which contributed to unrest within the empire.

Cultural and Religious Influence

Roman influence on the culture and religion of Gaul was profound. Roman gods and religious practices were adopted by the Gauls, who incorporated Roman deities such as Jupiter and Mars into their existing pantheons. Temples dedicated to these gods were built across the region, often in the centers of newly established Roman cities. The Temple of Augustus and Livia in Vienne (modern-day region of Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes) is a prime example of the integration of Roman religious architecture in Gaul.

In addition to religion, Roman theater and amphitheaters became central to cultural life. These structures, used for public performances, gladiatorial games, and other spectacles, served as symbols of Roman civilization. The Arles Amphitheater and the Nîmes Arena remain well-preserved examples of Roman engineering and entertainment in Gaul.

Decline and Invasions (200 CE – 350 CE)

Early Signs of Decline (200–250 CE)

By the early 3rd century CE, Roman Gaul faced increasing pressure from Germanic tribes such as the Franks and Alemanni. In addition, frequent changes in Roman leadership during the Crisis of the Third Century (235–284 CE) led to inconsistent governance in Gaul. Emperors often prioritized securing their own rule over addressing the province’s growing vulnerabilities. This instability resulted in high taxation to finance Rome’s continuous military campaigns, which burdened Gaul’s economy and led to widespread dissatisfaction among the local population.

As Roman authority weakened, some provincial governors and local leaders began exercising greater autonomy, resisting imperial mandates and even negotiating with invading tribes for protection. The growing reliance on mercenary troops, including Germanic auxiliaries, further blurred the distinction between Rome and its so-called “barbarian” enemies. By 250 CE, the fractures in Roman control were becoming evident, setting the stage for the emergence of breakaway territories.

The Gallic Empire (260–274 CE)

In 260 CE, a breakaway state known as the Gallic Empire was established by the usurper Postumus. This independent empire ruled over Gaul, Britannia, and parts of Hispania, providing temporary stability. However, internal strife weakened the Gallic rulers, and in 274 CE, Emperor Aurelian successfully reintegrated Gaul into the Roman Empire.

Military and Administrative Reforms (270–300 CE)

During this period, the Roman Empire faced increasing threats from external invaders and internal instability. In response, several military and administrative reforms were enacted to strengthen Gallia’s defenses and governance.

Fortification of Borders: Emperors like Aurelian and Diocletian reinforced military defenses along the Rhine frontier, constructing new fortifications and improving existing ones to prevent Germanic invasions.

Reorganization of the Military: The Roman army in Gallia was reorganized, with a greater emphasis on mobile field armies (comitatenses) rather than relying solely on frontier legions. This allowed for a more flexible and responsive military strategy.

Provincial Reforms: Under Diocletian’s Tetrarchy system, Gallia was divided into smaller, more manageable provinces to improve administrative efficiency and governance.

Constantine and Temporary Revival (306–337 CE)

Under Constantine the Great, Gallia experienced a temporary resurgence. The city of Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier) became one of the four imperial capitals of the Tetrarchy and later served as Constantine’s main residence from 306 to 316 CE. The city flourished with new construction, including an imperial palace, a massive basilica (the Aula Palatina), and a military headquarters, reinforcing its status as a key administrative center.

Constantine’s military campaigns secured the region from external threats, particularly against the Germanic tribes along the Rhine. In 310 CE, he launched a successful offensive against the Franks, fortifying the border and establishing military settlements to ensure stability.

His legalization of Christianity through the Edict of Milan in 313 CE began transforming the religious landscape of Gallia. The first Christian churches were established in cities like Lyon and Trier, where early bishops played a crucial role in spreading the faith.

Renewed Barbarian Pressure (337–350 CE)

The death of Emperor Constantine the Great in 337 CE triggered a period of instability across the Roman Empire, particularly in the western provinces. The division of the empire among his sons led to internal power struggles, weakening imperial control over key frontier regions, including Gaul.

This political fragmentation coincided with increasing external threats, as Germanic tribes, particularly the Franks and Alamanni, took advantage of Rome’s weakened grip. Throughout the late 330s and 340s, Roman defenses in Gaul were repeatedly tested.

The situation worsened as internal divisions within the empire deepened. In 350 CE, the general Magnentius seized power by overthrowing the western emperor, Constans, plunging the region into further turmoil.

End of Roman Rule and Transition (350 CE – 500 CE)

By the mid-4th century CE, barbarian groups continued to pressure Roman borders. In 406 CE, the Rhine frontier collapsed, and Vandals, Suebi, and Alans flooded into Gaul. The Roman administration struggled to maintain control, relying on treaties with Germanic groups like the Franks to defend the region.

The Goths, who had sacked Rome in 410, established a capital in Toulouse and in 418 succeeded in being accepted by Emperor Honorius as foederati, ruling over Aquitania in exchange for military assistance. Meanwhile, other Germanic groups such as the Burgundians and Franks expanded their influence.

In 451 CE, Roman general Flavius Aetius, with Visigothic support, halted the advance of Attila the Hun at the Battle of Châlons. However, Roman authority in Gaul was collapsing. Between 455 and 476, control shifted to the Visigoths, Burgundians, and Franks.

In 486 CE, Clovis I and the Franks defeated the last Roman forces at Soissons, marking the true end of Roman rule in Gaul. Following the collapse of Roman administration, the region gradually fell under the dominion of the Merovingian dynasty. The Merovingians consolidated their rule over much of Gaul, establishing the foundations of a nascent Frankish kingdom.

…….

Related articles:

Roman Gaul – New World Encyclopedia

Most Surprising Facts About Julius Caesar

The Rise and Fall of Rome: A Periodization of Roman History

Images:

Lionel Royer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Renato de carvalho ferreira, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Christophe BENOIST, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons