Prehistoric Period (up to 5th Century CE)

Poland’s earliest inhabitants date back to the Paleolithic era, around 200,000 years ago. Archaeological evidence shows the presence of Neanderthal and later Homo sapiens groups. By the Neolithic period (circa 4500 BCE), agricultural communities began to flourish, bringing advancements like pottery and early trade. The Bronze and Iron Ages saw the emergence of distinct cultures, such as the Lusatian culture, known for its fortified settlements.

During the Roman period (1st–5th centuries CE), the territory was inhabited by Celtic and Germanic tribes, such as the Goths and Vandals, who were part of broader migratory movements across Europe. These groups interacted with the Roman Empire through trade and sporadic conflicts, although Roman influence in Poland was indirect.

Slavic Settlement (6th–9th Centuries)

The Slavic peoples migrated into the region during the 6th century. They established small agricultural communities and gradually replaced earlier tribes. By the 9th century, these Slavic groups organized into tribal confederations, such as the Polans (after whom Poland is named), the Vistulans, and the Pomeranians.

The Polans, centered around the region of Greater Poland (Wielkopolska), began to dominate their neighbors under the leadership of powerful local chieftains. This laid the groundwork for the emergence of a centralized state.

Formation of the Piast State (10th–11th Centuries)

The foundation of Poland as a state is traditionally attributed to Duke Mieszko I of the Polans, who ruled from around 960 to 992. In 966, Mieszko converted to Christianity, aligning Poland with the Latin Church and Western Europe. This event, known as the “Baptism of Poland,” marked a pivotal moment in Polish history. Christianity brought new cultural, political, and economic ties to the rest of Europe.

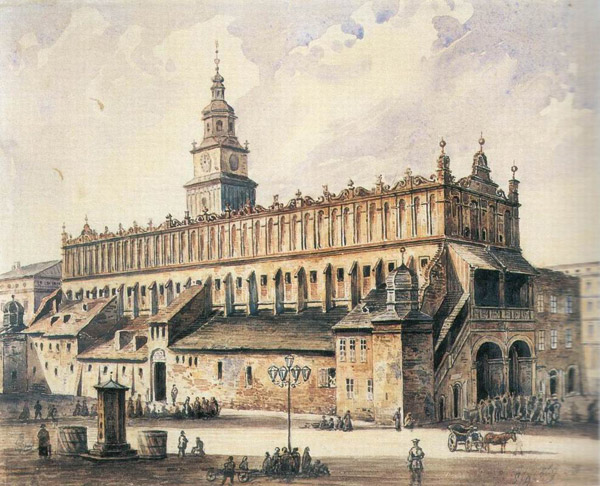

Mieszko’s dynasty, the Piasts, consolidated power by uniting various Slavic tribes under their rule. His son, Bolesław I the Brave (ruled 992–1025), became Poland’s first king. He expanded the realm and strengthened its institutions, earning Poland recognition as a kingdom in 1025. The period also saw the establishment of key cities like Gniezno, Poznań, and Kraków as religious and administrative centers.

Medieval Fragmentation (12th–13th Centuries)

After the death of Bolesław III Wrymouth in 1138, Poland entered a period of feudal fragmentation. His kingdom was divided among his sons, leading to rival duchies often embroiled in internal conflicts. This decentralized era weakened the monarchy and made Poland vulnerable to external threats, such as raids by the Mongols in 1241.

Despite this political disunity, the period saw the growth of towns and trade. The introduction of Magdeburg Law helped urban centers like Kraków and Wrocław thrive. It also brought German settlers, who influenced the region’s demographic and cultural landscape.

Reunification and Rise of a Strong Monarchy (14th Century)

In the late 13th and early 14th centuries, efforts to reunite Poland began under the Piast kings of Lesser Poland. Władysław I the Elbow-high (1306–1333) successfully reclaimed much of the fragmented territories and was crowned king in 1320, marking the restoration of a unified Polish kingdom.

His son, Casimir III the Great (1333–1370), strengthened the state through legal and administrative reforms. Known as “the Peasant King,” Casimir codified Polish law, encouraged economic development, and founded the University of Kraków in 1364, one of Europe’s oldest universities.

Union with Lithuania and the Jagiellonian Era (1385–1572)

The Union of Krewo (1385)

Casimir III’s death left Poland without a male heir, ending the Piast dynasty. The throne passed to his nephew Louis I of Hungary, and upon his death, his daughter Jadwiga became the ruler of Poland. In 1385, she married Jogaila, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, forming the Polish-Lithuanian Union through the Union of Krewo. Jogaila converted to Christianity, adopting the name Władysław II Jagiełło, and became king of Poland. This dynastic union brought together two vast territories under a single crown, creating one of the largest states in Europe.

Victory at Grunwald (1410)

Under the Jagiellonian dynasty, Poland and Lithuania confronted external threats, notably the Teutonic Order. The pivotal victory at the Battle of Grunwald (1410) marked a significant decline in the Order’s power and solidified the alliance’s dominance in Eastern Europe.

Golden Age of the Jagiellonians (15th–16th Centuries)

The 15th and early 16th centuries were a period of economic growth, cultural flourishing, and relative peace. Cities like Kraków became centers of trade, learning, and art. Casimir IV Jagiellon (1447–1492) successfully incorporated Prussia into the kingdom after the Thirteen Years’ War (1454–1466). His successors, particularly Sigismund I the Old (1506–1548) and Sigismund II Augustus (1548–1572), presided over the Polish Renaissance, fostering a thriving intellectual and artistic scene influenced by Italian and humanist traditions.

Union of Lublin (1569)

The Union of Lublin transformed the Polish-Lithuanian alliance into a formal state, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, in 1569. This dual monarchy was governed by a single elected monarch and a shared parliament (Sejm). The Commonwealth became a unique model of constitutional monarchy in Europe.

The Elective Monarchy and the Decline of the Commonwealth (1572–1795)

The Henrician Articles (1573)

Following the death of Sigismund II Augustus without heirs in 1572, the Commonwealth adopted an elective monarchy, allowing nobles to choose the king. This system was codified through the Henrician Articles, which guaranteed the nobility’s rights and established a system of checks on royal power. However, this led to political instability as foreign powers often interfered in elections.

Wars and Internal Struggles (17th Century)

The 17th century was marked by frequent wars that drained the Commonwealth’s resources:

The Deluge (1648–1667): A series of devastating wars, including a Swedish invasion and a Cossack uprising, led to significant territorial losses and economic decline.

Wars with the Ottoman Empire: Poland-Lithuania played a key role in the victory at the Battle of Vienna (1683), led by King John III Sobieski, which halted Ottoman expansion into Europe.

Decline of the Commonwealth (18th Century)

Internal political paralysis, known as the “Golden Liberty”, allowed the nobility to block decisions through the liberum veto. This weakened the state, leaving it vulnerable to external manipulation by Russia, Prussia, and Austria.

Partitions of Poland (1772, 1793, 1795)

The weakened Commonwealth was gradually partitioned by its neighbors:

- First Partition (1772): Russia, Prussia, and Austria seized significant territories.

- Second Partition (1793): A further loss of land followed reforms aimed at revitalizing the state.

- Third Partition (1795): Poland was erased from the map, with its territory fully divided among the three powers.

The Partitioned Era (1795–1918)

Napoleonic Era (1807–1815)

During the Napoleonic Wars, a brief Polish state, the Duchy of Warsaw, was established under Napoleon’s protection. However, it was dissolved after his defeat in 1815, and Poland was divided again.

19th-Century National Movements

Poles resisted partition through uprisings:

- November Uprising (1830–1831) and January Uprising (1863–1864) against Russian rule.

- Cultural preservation efforts, such as maintaining the Polish language and traditions, became central to resistance during this time.

The Second Polish Republic (1918–1939)

Rebirth of Poland

After 123 years of partition, Poland regained independence on November 11, 1918, following World War I. The collapse of the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and German empires allowed for the reestablishment of a Polish state. Józef Piłsudski, a military leader and nationalist, became a central figure in the formation of the new republic.

Borders and Conflicts

Establishing Poland’s borders required military action and diplomacy:

- Polish-Soviet War (1919–1921): Poland defended its eastern territories against the Soviet Union, securing victory in the Battle of Warsaw (1920), known as the “Miracle on the Vistula.”

- Treaty of Riga (1921): This treaty established Poland’s eastern border, incorporating parts of present-day Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania.

Political and Economic Challenges

The interwar period was marked by internal struggles:

- Political Instability: Poland adopted a parliamentary system, but frequent changes in government created instability.

- Piłsudski’s Coup (1926): Piłsudski seized power in a military coup, establishing an authoritarian regime while maintaining Poland’s independence.

- Economic Struggles: Poland faced difficulties in uniting its diverse regions, recovering from wartime devastation, and dealing with the Great Depression.

World War II and German-Soviet Occupation (1939–1945)

The Outbreak of War

On September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, triggering World War II. Seventeen days later, the Soviet Union invaded from the east under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, dividing Poland between the two powers.

Occupation and Resistance

- German Occupation: The Nazis implemented brutal policies, including mass executions, the establishment of ghettos, and the Holocaust, which resulted in the deaths of 3 million Polish Jews and millions of other citizens.

- Soviet Occupation: The Soviets deported hundreds of thousands of Poles to Siberia and conducted atrocities such as the Katyn Massacre (1940), where thousands of Polish officers were executed.

- Resistance: The Polish Underground State and the Home Army (Armia Krajowa) coordinated resistance efforts, including the Warsaw Uprising (1944) against German occupation, which ended in tragic defeat.

The People’s Republic of Poland (1945–1989)

Soviet Dominance

Poland became a communist state under Soviet influence. The government was dominated by the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR), and dissent was suppressed.

Economic and Social Challenges

- Nationalization: Industries were nationalized, and collectivization of agriculture was attempted but met resistance.

- Economic Struggles: Chronic shortages, inefficiency, and strikes plagued the economy.

- Opposition Movements: Despite repression, opposition grew, led by figures like Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński and workers’ groups.

Solidarity Movement

In the 1980s, the labor union Solidarity (Solidarność), led by Lech Wałęsa, emerged as a major force for change. Strikes and protests challenged the communist regime, forcing concessions.

Martial Law (1981–1983)

The communist government, under General Wojciech Jaruzelski, declared martial law to suppress Solidarity. Despite this, opposition to communism continued to grow.

The Fall of Communism and the Third Polish Republic (1989–Present)

Democratic Transition

The collapse of communism in Eastern Europe began in Poland:

- Round Table Talks (1989): Negotiations between the government and opposition led to partially free elections. Solidarity won a decisive victory, marking the end of communist rule.

- Lech Wałęsa became Poland’s first democratically elected president in 1990.

European Integration

Poland embraced democracy and a market economy, with significant milestones:

- NATO Membership (1999): Poland joined NATO, aligning itself with the West.

- EU Membership (2004): Poland became a member of the European Union, boosting economic growth and strengthening ties with Europe.