The Gaza Strip, a small but historically significant piece of land on the eastern Mediterranean coast, has been at the crossroads of civilizations for thousands of years. Its history is marked by conquests, shifting rulers, and ongoing geopolitical struggles. This article provides a comprehensive history of the Gaza Strip, tracing its past from antiquity to the present.

Egyptian and Philistine Rule

Gaza’s history dates back to at least 3000 BCE, when it emerged as a strategic hub along vital trade routes connecting Egypt, the Levant, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia. Due to its prime location on the Via Maris, an ancient trade and military route, Gaza became a key center for commerce, facilitating the exchange of goods, culture, and ideas between civilizations.

For much of the early period, Gaza was under Egyptian control, serving as an important administrative and military outpost for Egyptian rulers. The city was part of the Canaanite culture, with evidence of Egyptian temples and artifacts found in the region. The Pharaohs used Gaza as a staging ground for their military campaigns into the Levant and a center for collecting tribute from surrounding regions.

Around 1200 BCE, during the widespread collapse of Bronze Age civilizations, a new group of settlers—the Philistines—arrived in the region. The Philistines were part of the mysterious Sea Peoples, a confederation of maritime invaders who disrupted civilizations across the Eastern Mediterranean. They settled in the coastal region of Canaan, establishing the Pentapolis—a league of five key cities, which included Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Gath.

Gaza quickly became one of the most prominent Philistine cities, serving as a political, military, and religious center. The Philistines were known for their distinct material culture, including advanced pottery, iron weaponry, and their unique religious practices. Unlike the Canaanites, who were influenced by Mesopotamian and Egyptian traditions, the Philistines had strong ties to Aegean and Anatolian cultures, suggesting their origins may have been in regions like Crete or Mycenaean Greece.

The Philistines became formidable adversaries of the Israelites, who were settling in the hill country of Canaan at the same time. The Hebrew Bible frequently describes battles between the Philistines and Israelite leaders, including Samson, Saul, and David. One of the most famous biblical accounts involves Samson, who was said to have been captured and blinded in Gaza before bringing down the temple of the Philistine god Dagon in an act of revenge.

By the 10th century BCE, the power of the Philistines began to wane as they faced military defeats, most notably under King David, who incorporated parts of Philistine territory into the United Kingdom of Israel.

Persian Rule in Gaza (6th–4th Century BCE)

With the fall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 539 BCE, Cyrus the Great of Persia conquered the region, incorporating Gaza into the vast Achaemenid Empire. Under Persian rule, Gaza remained a key administrative and commercial center, benefiting from the empire’s vast network of roads and trade routes.

The Persians also relied on Gaza’s coastal position for their naval ambitions in the eastern Mediterranean. Persian kings, particularly Darius I (522–486 BCE) and Xerxes I (486–465 BCE), invested in strengthening their naval forces, utilizing Phoenician, Egyptian, and Cypriot fleets. Gaza’s location ensured its continued prominence as a maritime center supplying provisions and acting as a transit point for goods.

Hellenistic Rule in Gaza (4th–1st Century BCE)

After Alexander the Great’s conquest in 332 BCE, Gaza became part of the expanding Hellenistic world. Alexander recognized the city’s strategic importance, positioning it as a key gateway between Egypt, the Levant, and the Mediterranean trade routes. However, his brutal siege and destruction of the city left a lasting mark, as much of Gaza had to be rebuilt following its conquest.

Following Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, his vast empire was divided among his generals. Gaza, like much of the Levant, became contested between two rival successor states: the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt and the Seleucid Empire of Syria. The Egyptian-based Ptolemaic dynasty, founded by Alexander’s general Ptolemy I, controlled Gaza for much of the 3rd century BCE. Around 200 BCE, after a series of wars between the Ptolemies and the Seleucids, Gaza fell under the control of the Seleucid Empire, ruled by Antiochus III. The Seleucids promoted Hellenization, encouraging Greek customs, philosophy, and religious practices.

The Hasmonean Conquest and Jewish Influence

By the 2nd century BCE, as the Seleucid Empire weakened, the region became contested once again. In 96 BCE, Alexander Jannaeus, the Hasmonean king of Judea, conquered Gaza, incorporating it into his expanding Jewish kingdom. The conquest led to a shift in the city’s religious and cultural identity. Jannaeus, who was known for his harsh treatment of non-Jewish populations, reportedly destroyed much of Gaza and expelled many of its Greek and pagan inhabitants.

Gaza Under Roman Rule (1st Century BCE – 4th Century CE)

In 63 BCE, the Roman general Pompey the Great conquered the Levant, bringing Gaza under the control of the expanding Roman Republic. Gaza, which had been under Hasmonean rule for several decades, was restored as a Hellenistic city by Pompey, who sought to strengthen Rome’s influence in the region. Under Roman administration, Gaza regained its status as a major trade hub, connecting Egypt, Arabia, and the Mediterranean world.

The city benefited from Roman roads, aqueducts, and administrative stability, which encouraged trade and urban development. Gaza’s port facilitated commerce with Italy, Greece, and the rest of the empire, and the city became known for its exports, including incense, spices, wine, and textiles.

During the first three centuries of Roman rule, pagan religious practices flourished in Gaza. The city was home to several grand temples, the most famous being the Marneion, a massive temple dedicated to Marnas, the chief deity of Gaza, worshipped as a god of fertility and rain. Greek and Roman gods such as Zeus, Apollo, and Aphrodite were also venerated in Gaza, with temples and shrines dedicated to them.

Gaza’s religious diversity also included a significant Jewish population, which coexisted alongside its Greco-Roman inhabitants. However, tensions occasionally flared between Jews and pagans, particularly during the Jewish Revolts against Rome (66–135 CE), which led to violent clashes in the region.

By the 3rd and 4th centuries CE, Christianity began to spread in Gaza, as it did across the Roman Empire. However, Gaza remained a stronghold of paganism longer than many other cities in the region. The Marneion temple and its priesthood continued to wield great influence, resisting the Christianization that was taking hold elsewhere.

This changed dramatically in the late 4th century, when Emperor Theodosius I (r. 379–395 CE) declared Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire and ordered the closure of pagan temples. In 402 CE, the Christian bishop Porphyry of Gaza, with support from Emperor Arcadius, led efforts to destroy the Marneion and other pagan sites in Gaza.

Gaza Under Byzantine Rule (4th–7th Century CE)

With the rise of the Byzantine Empire (the Eastern Roman Empire) in the 4th century CE, Gaza became a major center of Christian learning and monasticism. The city, once a stronghold of paganism, was transformed into one of the leading Christian cities in the eastern Mediterranean.

The city became home to notable Christian scholars, theologians, and philosophers, including Procopius of Gaza, who contributed to the development of Christian rhetoric and biblical interpretation.

By the 6th century, the Byzantine Empire faced increasing challenges. The Sassanian Persians, Rome’s long-time rival, launched devastating invasions into the eastern provinces. In 614 CE, Persian forces under Khosrow II captured Gaza along with Jerusalem, temporarily ending Byzantine rule in the region. The Persians allowed Jewish populations to return and govern some areas, but their control was short-lived.

The Byzantine emperor Heraclius launched a counteroffensive, retaking Gaza and much of the Levant in 628 CE. However, the region’s instability weakened Byzantine authority, making it vulnerable to a new and powerful force rising in Arabia—the Muslim Caliphate.

Early Islamic Period

In the 7th century, the Byzantine Empire’s control over Gaza came to an end with the rapid expansion of Islam. The region, including Gaza, was among the first to fall to the advancing Muslim forces.

In 636 CE, Muslim armies led by Caliph Umar conquered Gaza, bringing it under Islamic rule. The transition from Byzantine to Islamic rule was relatively smooth, as the new rulers allowed religious tolerance for Christian and Jewish communities in exchange for the jizya tax. Gaza became a key hub of Islamic culture and scholarship. Over the centuries, it changed hands between different Muslim dynasties, including the Umayyads, Abbasids, and Fatimids.

The Abbasid Caliphate and the Decline of Gaza (8th–10th Century)

When the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyads in 750 CE, Gaza’s status began to decline. The Abbasid Caliphate focused its power on Baghdad, shifting trade routes and political attention away from the Levant. The city suffered from economic stagnation and occasional rebellions, as different factions vied for control. During this period, Gaza was frequently caught in conflicts between the Abbasids and local rulers, such as the Tulunids of Egypt (9th century) and later the Ikhshidids (10th century).

The Fatimid Caliphate and Turmoil (10th–12th Century)

In the 10th century, Gaza came under the control of the Fatimid Caliphate, an Ismaili Shia dynasty ruling from Egypt. The Fatimids heavily fortified Gaza, recognizing its strategic importance. However, the city became a battleground in the ongoing wars between the Fatimids, Seljuk Turks, and Crusaders.

Gaza Under the Crusaders and Ayyubids (12th–13th Century)

The 12th century marked a turbulent period for Gaza as it became a battleground during the Crusades. The city changed hands multiple times between Christian Crusaders and Muslim forces, suffering destruction and depopulation in the process.

After the First Crusade (1096–1099), Crusader forces established the Kingdom of Jerusalem, expanding their control across much of the Levant. In 1100, Gaza was taken by King Baldwin I of Jerusalem, who incorporated it into his growing Crusader kingdom.

During this period, the Crusaders built fortifications in Gaza to defend the southern frontier of their kingdom against attacks from Egypt. However, the city never regained its former importance, as its trade routes had been severely disrupted by war. Gaza became more of a military outpost than a thriving economic hub.

Despite Crusader control, the local Muslim and Jewish populations remained, though they lived under restrictive laws and heavy taxation. Christian settlers and military orders, such as the Knights Templar, were stationed in the region to defend against Muslim counterattacks.

In 1187, the great Muslim general Salah al-Din (Saladin) led a decisive campaign against the Crusaders, culminating in his victory at the Battle of Hattin. Shortly after, Gaza was retaken by Muslim forces, returning it to Islamic rule under the Ayyubid Sultanate.

Saladin and his successors dismantled the Crusader fortifications and restored Gaza as a strategic military base to defend against future Crusader invasions. Under the Ayyubids, efforts were made to revitalize trade and repopulate the city, though it took time for Gaza to recover from decades of warfare.

The Crusaders made several attempts to recapture Gaza, but they were ultimately unsuccessful. By the mid-13th century, Crusader power was waning, and the city firmly remained under Muslim control.

Gaza Under the Mamluks (13th–16th Century)

The Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517) brought stability and prosperity back to Gaza after the destruction of the Crusades. Under Mamluk rule, Gaza became a key administrative, military, and trade center linking Egypt, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula.

Under the Mamluks, Gaza was transformed into a key military outpost defending Egypt from invasions by Mongols and Crusaders. The city was heavily fortified, with new mosques, madrasas (Islamic schools), and caravanserais (resting places for merchants and travelers) constructed to encourage trade and settlement.

The Mamluks also improved infrastructure by building roads and bridges, strengthening Gaza’s role as a major station along trade routes connecting Cairo, Damascus, and Mecca.

With the revival of trade, Gaza became an important center for the spice trade, as goods from India and the Red Sea passed through on their way to Mediterranean markets. The city’s economy benefited from textiles, pottery, and agricultural products, while religious institutions flourished under Mamluk patronage.

Ottoman Rule (1517–1917)

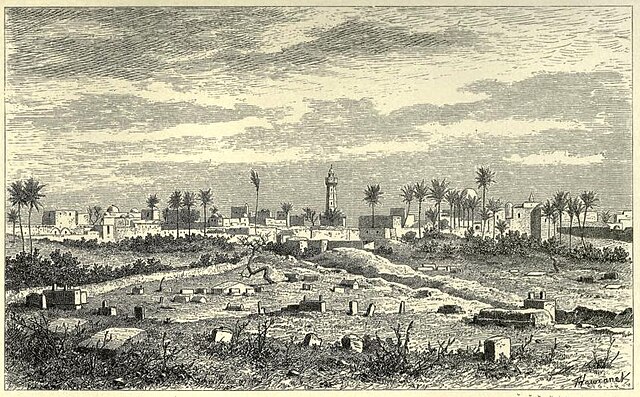

The Ottoman Empire ruled Gaza from 1516 to 1917. Under Ottoman administration, Gaza remained an important regional center for trade, military defense, and religious scholarship. However, shifting political and economic conditions led to its eventual stagnation.

One of the most famous Ottoman governors of Gaza was Ridwan Pasha, who ruled in the 16th century. The Ridwan dynasty, a powerful local family, controlled Gaza for nearly a century, bringing a period of relative autonomy and prosperity. Ridwan Pasha and his descendants invested in infrastructure, trade, and religious institutions, enhancing Gaza’s significance within the empire.

By the 18th century, Gaza, like much of the Ottoman Empire, began to experience economic decline. The rise of European maritime trade routes reduced the importance of overland trade through the Levant, weakening Gaza’s economy. In addition, Ottoman central authority weakened, leading to increasing control by local warlords and rival factions.

In the early 19th century, Gaza was caught between Ottoman rule and Egyptian expansion. In 1831, Muhammad Ali of Egypt invaded Palestine, and Gaza briefly fell under Egyptian control. However, by 1840, the Ottomans, with British support, restored their authority over the city.

Despite its decline, the late 19th century saw some attempts at modernization. The Ottomans built new roads, telegraph lines, and administrative buildings, linking Gaza more closely to major cities like Jerusalem and Damascus. European influence grew, with missionary schools and consulates appearing in the region.

However, the weakening Ottoman state struggled to maintain order. Bedouin raids, internal unrest, and economic stagnation plagued Gaza, and the city remained largely impoverished.

World War I and British Rule in Gaza (1917–1948)

During World War I (1914–1918), Gaza became a major battleground between the Ottoman Empire, allied with Germany, and the British-led forces, which sought to take control of Palestine. The First (March 1917) and Second (April 1917) Battles of Gaza resulted in Ottoman victories, as they successfully repelled British advances. However, in the Third Battle of Gaza (November 1917), the British Egyptian Expeditionary Force, led by General Edmund Allenby, launched a decisive offensive. The Ottomans, unable to hold their positions, retreated, and Gaza fell to British control.

Following the League of Nations mandate system, Britain was granted control over Palestine, including Gaza, in 1920. This period marked the beginning of significant political and social changes in the region.

The British administration initially attempted to maintain order and stability while balancing conflicting interests between Arabs and Jews, whose political aspirations increasingly clashed. The Balfour Declaration (1917)—a British statement supporting a Jewish homeland in Palestine—heightened tensions, as the Arab population strongly opposed Jewish immigration and land purchases.

As Jewish immigration to Palestine increased under British rule, Arab resistance grew. The 1920s and 1930s saw repeated protests, riots, and strikes against British policies and Zionist expansion. The Arab Revolt (1936–1939) was a major uprising against both British rule and Jewish immigration, with Gaza playing a role as a center of resistance.

During World War II (1939–1945), Palestine, including Gaza, remained under British control. The war further intensified Jewish-Arab tensions, as Jewish militias, such as the Haganah and Irgun, began armed resistance against British rule, demanding a Jewish state.

By the late 1940s, the British found themselves unable to control the escalating violence between Jews and Arabs. Exhausted by World War II, Britain decided to withdraw from Palestine and handed the issue over to the United Nations (UN). In 1947, the UN proposed a Partition Plan, which sought to divide Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states, with an international status for Jerusalem.

The UN Partition Plan was rejected by Arab leaders, including Palestinian leaders in Gaza, who saw it as a violation of their national rights. As tensions escalated, violence broke out between Jews and Arabs, culminating in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War after Britain formally withdrew in May 1948.

The 1948 War and Egyptian Control

The 1948 Arab-Israeli War broke out immediately after the British withdrawal from Palestine on May 14, 1948, and the declaration of the State of Israel. Palestinian Arabs, along with neighboring Arab countries—including Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq—launched a military intervention to prevent the establishment of Israel and to secure Palestinian territories.

During the war, Egyptian forces advanced into southern Palestine, including Gaza, intending to prevent Israeli expansion. The Egyptian army took control of Gaza City and the surrounding coastal region, turning it into an important base of operations against Israeli forces.

An armistice agreement was signed in February 1949 between Egypt and Israel. The agreement left Gaza under Egyptian military control, while Israel solidified its hold over the rest of historical Palestine. Many Palestinian cities and villages were destroyed, and hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were expelled or fled in what became known as the Nakba (Catastrophe).

After the war, Gaza’s population drastically increased, as nearly 200,000 Palestinian refugees—fleeing violence and Israeli expansion—were forced into the small territory. The region, previously home to around 80,000 people, became overcrowded with refugees living in dire conditions in makeshift camps. These camps, managed by the newly established United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), lacked adequate resources, infrastructure, and employment opportunities. Poverty and despair became defining features of life in Gaza under Egyptian rule.

Egypt never annexed Gaza as Jordan did with the West Bank, instead treating it as a separate military-occupied territory. Gaza was ruled by an Egyptian military governor, and Palestinians had no political representation in Egypt. Although Egypt claimed to support Palestinian self-determination, it strictly controlled political activity in Gaza, banning the formation of independent Palestinian political parties and suppressing opposition movements.

Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, Palestinian Fedayeen fighters—many of them displaced refugees—began launching cross-border raids into Israel from Gaza. These attacks targeted Israeli settlements and military positions, prompting harsh Israeli retaliations, including airstrikes and military incursions into Gaza. The cycle of raids and counter-raids heightened tensions between Egypt and Israel, further militarizing the region.

In response to these attacks, Israel carried out large-scale military operations against Gaza, including the 1955 Operation Black Arrow, which resulted in dozens of deaths and marked the beginning of Israel’s aggressive military policy against Palestinian resistance in Gaza.

By the 1960s, the desire for Palestinian self-governance was increasing. In 1964, Egypt supported the formation of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which aimed to represent Palestinians and fight for their independence.

The Six-Day War (1967)

Tensions between Israel and its Arab neighbors escalated throughout the 1960s. In June 1967, the situation exploded into the Six-Day War, in which Israel launched a preemptive strike against Egypt, Jordan, and Syria.

On June 5, 1967, Israeli forces swiftly defeated the Egyptian army and occupied Gaza and the Sinai Peninsula. By June 10, Israel had also captured the West Bank and East Jerusalem from Jordan and the Golan Heights from Syria.

The war marked the end of Egyptian rule over Gaza, as Israel imposed a military occupation that would last for nearly four decades (1967–2005).

First and Second Intifadas

Growing Palestinian frustration led to the First Intifada (1987–1993)—a mass uprising against Israeli control, marked by protests, boycotts, and violence. This led to the Oslo Accords (1993–1995), which granted the newly formed Palestinian Authority (PA) limited control over Gaza and parts of the West Bank. A second uprising, the Second Intifada (2000–2005), erupted after failed peace talks. Violence intensified, leading Israel to change its strategy in Gaza.

Israeli Disengagement (2005)

In 2004, Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, once a strong supporter of Israeli settlements, proposed a full withdrawal of Israeli forces and settlers from Gaza. His reasoning included:

- Growing international pressure to restart peace efforts.

- The high cost of maintaining security for 8,000 Israeli settlers living among 1.5 million Palestinians.

- The ongoing violence and resistance attacks from groups like Hamas and Islamic Jihad.

Despite opposition from Israeli right-wing groups and some settlers, Sharon’s plan was approved, and in August 2005, Israel began its withdrawal. About 8,500 Israeli settlers were forcibly removed from 21 settlements in Gaza, as well as four settlements in the northern West Bank. Israeli forces dismantled bases, outposts, and checkpoints and left Gaza on September 12, 2005. After the withdrawal, Israel retained control over Gaza’s airspace, coastline, and border crossings, while Egypt controlled the southern border at Rafah.

Hamas Takeover and Israeli Blockade (2007)

In 2006, Hamas won the Palestinian legislative elections, defeating the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority. A violent struggle between Hamas and Fatah resulted in Hamas seizing full control of Gaza in 2007. This led Israel and Egypt to impose a blockade on Gaza, citing security concerns over Hamas’ ties to militant groups.

—

Related:

Cultures of Predynastic Egypt: Unearthing the Foundations of a Great Civilization

History of the Question of Palestine – Question of Palestine