1. Ancient and Early History

Paleolithic Era (Old Stone Age)

- Human activity in what is now Germany dates back hundreds of thousands of years.

- Homo heidelbergensis: One of the earliest human ancestors, whose remains were discovered in Heidelberg, lived around 600,000 years ago.

- Neanderthals: Flourished in the region during the Middle Paleolithic (300,000–40,000 BCE). Significant archaeological sites include Neander Valley, where Neanderthal remains were first identified.

Mesolithic Era (Middle Stone Age, 10,000–5500 BCE):

- After the last Ice Age, hunter-gatherers inhabited Germany’s forests, rivers, and plains.

- Tools, microliths, and evidence of fishing and hunting activities have been found in sites like the Duvensee bog in northern Germany.

Neolithic Revolution (5500–2000 BCE)

The introduction of agriculture and domestication of animals marked a transformative period for Germanic lands.

- Linear Pottery Culture (5500–4500 BCE): One of the earliest farming cultures in Central Europe, characterized by distinctive pottery with linear decorations.

- Megalithic Monuments: Evidence of communal religious practices, with stone structures such as dolmens and passage graves, appears during this period.

The Bronze Age (2000–800 BCE)

The Bronze Age saw increased social complexity and technological innovation.

- Unetice Culture (2300–1600 BCE): Known for its bronze tools, weapons, and ornaments. Significant finds include the Nebra Sky Disk, an early depiction of the cosmos, found in Saxony-Anhalt.

- Tumulus and Urnfield Cultures: Burial practices shifted to mound graves (tumuli) and later cremation, with ashes buried in urns, reflecting evolving religious beliefs.

The Iron Age and Early Germanic Tribes (800 BCE–1 CE)

The Iron Age marked the rise of the Celtic and Germanic peoples in what is now Germany.

- Celtic Influence:

- The Celts dominated southern and western Germany, establishing settlements and trade routes.

- Important sites like the Heuneburg hillfort on the Upper Danube demonstrate advanced Celtic societies.

- Germanic Tribes:

- Germanic-speaking peoples began to emerge in northern and central Germany around 500 BCE.

- Early tribes, including the Suebi, Cherusci, and Cimbri, practiced subsistence farming and were organized into clans or small communities.

Germanic Tribes and Roman Encounters (1st Century BCE – 5th Century CE)

Early Germanic tribes, such as the Goths, Vandals, and Franks, occupied much of Central Europe. They famously resisted Roman expansion, with the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (9 CE) marking a turning point in Roman ambitions north of the Rhine.

The Migration Period (4th–6th Century)

The Migration Period, or Völkerwanderung (“migration of peoples”), was a transformative era in European history marked by the movement of Germanic tribes across the continent. Triggered by the decline of the Western Roman Empire and pressure from the advancing Huns, this period saw the fragmentation of Roman territories and the emergence of Germanic kingdoms.

Key events during this time include:

- The Rise of the Franks: The Franks, initially a loose confederation of tribes along the Rhine, began to consolidate under leaders like Clovis I. By the late 5th century, they had founded the Merovingian dynasty, which would dominate much of what is now France and Germany.

- Gothic Migrations: The Goths, divided into the Visigoths and Ostrogoths, were among the first to challenge Roman authority. After being displaced by the Huns, the Visigoths famously sacked Rome in 410 CE under King Alaric. They later established a kingdom in Spain.

- The Vandals’ Journey: The Vandals crossed the Rhine into Roman Gaul in 406 CE, eventually moving through Spain and into North Africa, where they established a kingdom that would become a significant threat to Roman maritime trade.

2. The Holy Roman Empire (800–1806)

Charlemagne and the Carolingian Empire (800):

The origins of the Holy Roman Empire can be traced to Charlemagne (Karl der Große), King of the Franks, who was crowned “Emperor of the Romans” by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day in 800. His empire encompassed much of Western and Central Europe, including large parts of modern Germany. Charlemagne’s reign symbolized the fusion of Roman, Germanic, and Christian traditions, which would define the Holy Roman Empire.

After Charlemagne’s death, the empire fragmented due to internal divisions and invasions. The Treaty of Verdun (843) divided his empire among his grandsons, creating separate kingdoms. The East Frankish Kingdom, which roughly corresponded to modern Germany, became the nucleus of the future Holy Roman Empire.

The Saxon Dynasty and Otto I (962):

The title of Holy Roman Emperor was revived in 962 by Otto I, also known as Otto the Great. A king of the East Frankish (German) Kingdom, Otto consolidated power by defeating rival duchies, securing the Church’s support, and repelling external threats like the Magyars at the Battle of Lechfeld (955). Otto’s coronation by the pope marked the formal establishment of the Holy Roman Empire, with Germany as its heartland.

Feudal Structure:

The empire was a decentralized confederation of kingdoms, duchies, principalities, and free cities. The emperor was elected by a group of powerful nobles, later formalized as the Prince-Electors, reflecting the empire’s fragmented nature. This system ensured that the emperor often had to negotiate power with local rulers, preventing strong central authority.

The Investiture Controversy (1076–1122):

A major conflict arose between the emperor and the pope over who held the authority to appoint bishops. This struggle, known as the Investiture Controversy, came to a head during the reign of Emperor Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII. It resulted in Henry IV’s dramatic penance at Canossa (1077) and a broader weakening of imperial authority. The Concordat of Worms (1122) resolved the issue by dividing authority over Church appointments.

The Hohenstaufen Dynasty (12th–13th Century):

The Hohenstaufen emperors, particularly Frederick I (Barbarossa) and Frederick II, sought to expand imperial power and prestige. Barbarossa attempted to assert control over Italy and strengthen the emperor’s authority, but his ambitions were thwarted by the Lombard League and papal opposition.

Frederick II, often called the “Stupor Mundi” (Wonder of the World), was a brilliant ruler who pursued cultural and scientific endeavors. However, his conflicts with the papacy and German princes further weakened central authority.s.

Fragmentation and Crisis (13th–15th Century)

The Great Interregnum (1250–1273):

Following the death of Frederick II, the empire entered a period of political disarray known as the Great Interregnum, during which no strong central authority emerged. Regional rulers and city-states gained significant autonomy.

The Rise of the Electors:

The Golden Bull of 1356, issued by Emperor Charles IV, formalized the process of electing the emperor. Seven prince-electors, including powerful rulers such as the King of Bohemia and the Archbishops of Mainz, Cologne, and Trier, were granted the exclusive right to choose the emperor. This entrenched the decentralized nature of the empire.

The Reformation and Religious Wars (16th–17th Century)

Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation (1517):

The Holy Roman Empire became the epicenter of the Protestant Reformation, sparked by Martin Luther’s 95 Theses in 1517. The movement divided the empire along religious lines, with many German princes adopting Protestantism to assert independence from the Catholic emperor.

The Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648):

Religious tensions escalated into one of Europe’s most devastating conflicts, the Thirty Years’ War. It began as a struggle between Catholic and Protestant states within the empire but expanded into a broader European war involving France, Sweden, and Spain. The war ravaged Germany, leading to massive population loss and economic ruin.

The Peace of Westphalia (1648) ended the war and effectively confirmed the empire’s fragmentation. It granted significant autonomy to individual states and recognized Calvinism alongside Catholicism and Lutheranism.

3. Unification and Empire (19th Century)

The Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire and Napoleonic Era (1806–1815)

Defeat of Napoleon and the Congress of Vienna (1815):

After Napoleon’s defeat, the Congress of Vienna restructured Europe, creating the German Confederation (Deutscher Bund), a loose association of 39 German states under Austrian leadership.

End of the Holy Roman Empire (1806):

Napoleon Bonaparte’s victories over Austria and Prussia led to the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire. Emperor Francis II abdicated the imperial title, becoming Emperor Francis I of Austria. German territories were reorganized into the Confederation of the Rhine, a French-dominated alliance of German states.

The Napoleonic Wars:

Many German states, including Prussia and Austria, resisted Napoleon but were defeated in early conflicts. Napoleon’s reforms, such as the abolition of feudal privileges and the introduction of modern legal systems, influenced German society and governance.

The Age of Nationalism and Revolutions (1815–1848)

- German Nationalism:

The Napoleonic Wars had awakened nationalist sentiments among Germans, who sought unification and independence from foreign domination. Intellectual movements, such as Romanticism, emphasized shared language, culture, and history as the basis for national unity. - Economic Modernization:

The Zollverein (Customs Union), established in 1834 under Prussian leadership, eliminated internal tariffs among member states and fostered economic integration. This economic union excluded Austria, highlighting Prussia’s growing influence. - Revolutions of 1848:

Inspired by liberal and nationalist uprisings across Europe, Germans revolted in 1848, demanding constitutional reforms, national unification, and greater political freedoms. The Frankfurt Parliament attempted to draft a constitution for a unified Germany but failed due to disagreements over the role of Austria and the unwillingness of King Frederick William IV of Prussia to accept the crown from a popular assembly.

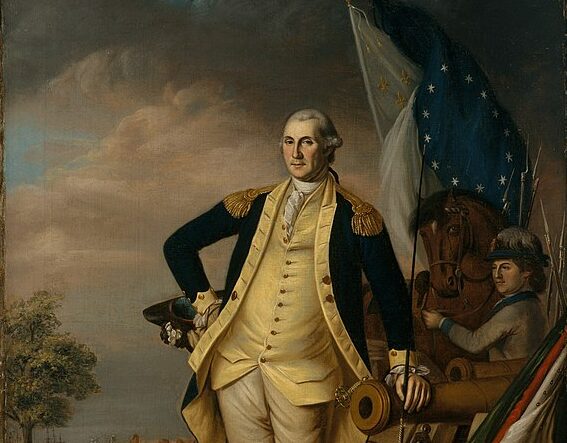

The Rise of Prussia and German Unification (1848–1871)

Proclamation of the German Empire (1871):

On January 18, 1871, the German Empire (Deutsches Kaiserreich) was proclaimed in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, with King Wilhelm I of Prussia becoming the first German Emperor (Kaiser). The empire, dominated by Prussia, became a federal monarchy with 25 states and a constitution.

Otto von Bismarck’s Leadership:

In 1862, Otto von Bismarck became Prime Minister of Prussia. A master of realpolitik (pragmatic politics), Bismarck used diplomacy, alliances, and military force to achieve German unification under Prussian dominance.

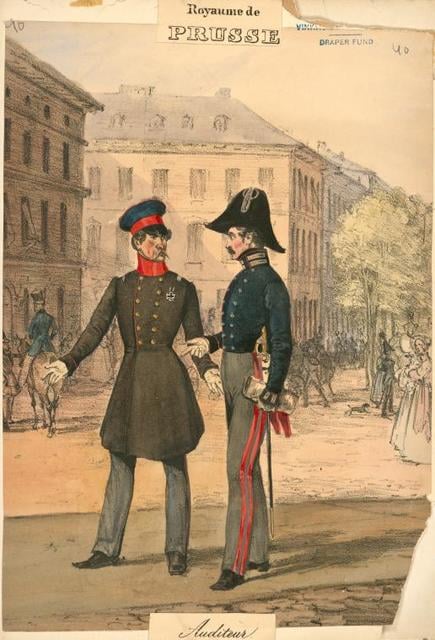

Wars of Unification:

Bismarck orchestrated three wars to unify Germany:

The Danish War (1864): Prussia and Austria defeated Denmark, gaining control of Schleswig and Holstein.

The Austro-Prussian War (1866): Prussia decisively defeated Austria, excluding it from German affairs and dissolving the German Confederation. The North German Confederation was established under Prussian leadership.

The Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871): Provoked by Bismarck, the war united northern and southern German states against France. Prussia’s victory and the capture of Paris humiliated France and solidified German unity.

The German Empire and Industrial Expansion (1871–1914)

- Economic Growth and Industrialization:

The late 19th century was a period of rapid industrialization in Germany. The nation became a leader in coal, steel, and chemical production, as well as in engineering and science. Urbanization increased, with cities like Berlin, Hamburg, and Munich expanding rapidly. - Cultural and Scientific Achievements:

Germany became a hub of cultural and scientific innovation, producing figures like physicist Albert Einstein, composer Richard Wagner, and philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. - Domestic Politics under Bismarck:

Bismarck pursued policies to consolidate the new empire:- Kulturkampf (Culture Struggle): Bismarck sought to limit the influence of the Catholic Church, viewing it as a threat to state authority.

- Social Reforms: To undermine the growing socialist movement, Bismarck introduced progressive labor laws, such as health insurance, accident insurance, and old-age pensions.

- Wilhelm II and the End of Bismarck’s Era (1890):

In 1888, Wilhelm II became emperor and sought a more assertive foreign policy, clashing with Bismarck. In 1890, Bismarck resigned, and Wilhelm pursued a more aggressive path, leading to tensions with other European powers. - Imperial Ambitions: Under Wilhelm II, Germany sought to expand its colonial empire, competing with Britain and France for influence in Africa and Asia. This aggressive expansion strained relations with other nations.

- Alliances and Militarization: Germany’s alliances with Austria-Hungary and Italy formed the Triple Alliance, countered by the Triple Entente of France, Russia, and Britain. Germany also invested heavily in its military, including a powerful navy, challenging British dominance at sea.

- Crises and Escalation: Several international crises, such as the Moroccan Crises (1905 and 1911) and the Balkan conflicts, increased tensions in Europe. Germany’s support for Austria-Hungary in these disputes deepened its rivalry with Russia and France.

German soldiers in WWI

4. The World Wars and Interwar Period (20th Century)

World War I and Its Aftermath (1914–1918)

Germany entered World War I as part of the Central Powers, alongside Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, against the Allies. The war began with Germany’s invasion of Belgium and France, a strategy rooted in the Schlieffen Plan, which aimed for a quick victory on the Western Front. However, the war devolved into a prolonged and devastating stalemate.

Collapse of the War Effort:

By 1918, Germany faced military defeat, economic collapse, and widespread social unrest. The failure of the spring offensives and the arrival of fresh American troops sealed Germany’s fate. The armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, marking the end of the war.

The Weimar Republic (1918–1933)

Formation and Challenges:

Revolution and Abdication of the Kaiser:

In November 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated, and Germany was declared a republic. The Weimar Republic, named after the city where the new constitution was drafted, was established in 1919. Friedrich Ebert of the Social Democratic Party became the first president.

Treaty of Versailles (1919):

The treaty imposed severe territorial, military, and economic penalties on Germany. Key provisions included:

- Loss of colonies and territories, including Alsace-Lorraine and parts of Prussia.

- Demilitarization of the Rhineland and limits on the German military.

- Reparations amounting to billions of marks.

- The “War Guilt Clause,” which held Germany solely responsible for the war.

Hyperinflation Crisis (1923):

Germany struggled to pay reparations, leading to the occupation of the Ruhr by French and Belgian forces. The government printed money to fund resistance, causing hyperinflation that wiped out savings and destabilized the economy.

Recovery under Stresemann:

Gustav Stresemann, as chancellor and foreign minister, stabilized the economy through the Dawes Plan (1924), which restructured reparations and secured foreign loans. Stresemann also improved Germany’s international standing, leading to its entry into the League of Nations in 1926.

The Great Depression (1929):

The global economic crisis hit Germany hard, causing mass unemployment and fueling disillusionment with the Weimar government. Extremist parties, including the Nazis and Communists, gained support.

The Rise of Nazi Germany (1933–1939)

Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party:

- Rise to Power:

Adolf Hitler, leader of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazi Party), exploited economic hardship and nationalist sentiment. In 1933, he was appointed chancellor. After the Reichstag Fire, he used emergency powers to suppress opposition. - Consolidation of Power:

Hitler quickly established a totalitarian regime:- The Enabling Act (1933) gave him dictatorial powers.

- Political parties were banned, and dissenters were imprisoned or killed.

- Propaganda, orchestrated by Joseph Goebbels, promoted Nazi ideology.

- Key Policies:

- Anti-Semitism: Jews were systematically marginalized through laws like the Nuremberg Laws (1935) and violent events like Kristallnacht (1938).

- Militarization: Hitler defied the Treaty of Versailles by rebuilding the military and reoccupying the Rhineland (1936).

- Territorial Expansion: Hitler pursued the unification of German-speaking peoples, leading to the Anschluss (annexation of Austria) in 1938 and the occupation of the Sudetenland after the Munich Agreement.

War II (1939–1945)

Outbreak of War:

- Invasion of Poland (1939):

Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, prompted Britain and France to declare war, starting World War II. The invasion used Blitzkrieg tactics, combining rapid mechanized assaults and airpower.

German Expansion (1939–1942):

- Germany quickly conquered much of Europe, including France, Denmark, Norway, and the Low Countries. The Battle of Britain (1940) marked Germany’s first major defeat, as the Luftwaffe failed to gain air superiority.

- Operation Barbarossa (1941):

Hitler launched a massive invasion of the Soviet Union, aiming to seize resources and destroy communism. Early successes were followed by a brutal winter and Soviet counterattacks, culminating in the defeat at Stalingrad (1943).

The Holocaust:

- The Nazi regime implemented the Final Solution, a systematic plan to exterminate Jews and other groups deemed undesirable. Over six million Jews, along with millions of Romani people, disabled individuals, political prisoners, and others, were murdered in concentration and extermination camps such as Auschwitz.

Turning Points (1942–1943):

- The Allies began to push back:

- North Africa: The Axis was defeated in the North African Campaign.

- Italy: The Allied invasion of Italy led to Mussolini’s fall and opened a southern front.

- Eastern Front: The Soviet victory at Stalingrad marked a turning point.

Collapse of Nazi Germany (1944–1945):

- D-Day (1944): The Allied invasion of Normandy opened a Western Front.

- Battle of the Bulge (1944–1945): Germany’s final offensive in the West failed.

- Fall of Berlin (1945): The Soviets captured Berlin in May 1945. Hitler committed suicide on April 30, and Germany unconditionally surrendered on May 8, 1945.

5. Post-War Division and Reunification (1945–1990)

Division of Germany:

Post-war Germany was split into East Germany (controlled by the Soviet Union) and West Germany (aligned with Western democracies). The Berlin Wall (1961) symbolized this division during the Cold War.

Economic Recovery and the “Economic Miracle”:

West Germany experienced rapid economic growth, becoming a key member of the European Economic Community (EEC). East Germany, under communist rule, faced stagnation and social unrest.

Reunification (1990):

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union led to Germany’s reunification in 1990, marking a new chapter in its history.