The history of Arab Spain, often referred to as Al-Andalus, spans a fascinating and transformative period that left a profound impact on the Iberian Peninsula.

The Muslim Conquest (711–718)

In 711, a Muslim army led by the Berber general Tariq ibn Ziyad crossed the Strait of Gibraltar from North Africa, defeating the Visigothic king Roderic at the Battle of Guadalete.

Within a few years, most of the Iberian Peninsula fell under Muslim control, with Cordoba, Seville, and Toledo becoming important centers. The region was named Al-Andalus.

The Consolidation of Muslim Rule (718–756)

After the Muslim forces, led by Tariq ibn Ziyad and Musa ibn Nusayr, rapidly conquered much of the Iberian Peninsula by 718, they faced the challenge of governing a large, diverse, and unfamiliar territory.

The Muslim forces encountered resistance in the northern regions, particularly from the Asturian Christians led by Pelagius. In 722, the Battle of Covadonga marked a small but symbolic Christian victory and the beginning of the Reconquista.

From Al-Andalus, Muslim forces sought to expand into Gaul (modern France). They advanced under the leadership of generals such as Abd al-Rahman al-Ghafiqi. In 732, at the Battle of Tours (or Poitiers), the Muslim army was defeated by the Frankish leader Charles Martel, halting further expansion into northern Europe.

A major Berber revolt broke out in Al-Andalus in 740, fueled by dissatisfaction over treatment and land allocations. Though suppressed by Arab forces, the revolt weakened Muslim control and destabilized the region.

Umayyad Emirate (756–929)

In 750, the Umayyad Caliphate in Damascus was overthrown by the Abbasid dynasty, leading to widespread purges of the Umayyad family. One Umayyad prince, Abd al-Rahman I, escaped and fled to Al-Andalus.

Abd al-Rahman I capitalized on the region’s instability and divided leadership to establish his authority. By 756, Abd al-Rahman I had successfully declared himself Emir of Cordoba, founding the Umayyad Emirate and marking a new chapter in the history of Al-Andalus.

This period saw relative stability and the integration of Arabs, Berbers, and native Iberians (including many converted to Islam) into Andalusian society.

The Golden Age: Umayyad Caliphate (929–1031)

In 929, Abd al-Rahman III declared himself Caliph, marking the height of Al-Andalus’s power and influence. Cordoba became a political, economic, and cultural hub of the Islamic world.

Advances in science, philosophy, medicine, and architecture flourished. The Great Mosque of Cordoba and scholars like Ibn Rushd (Averroes) and Maimonides (a Jewish philosopher) emerged as symbols of this era.

Fragmentation: The Taifas (1031–1086)

The Caliphate dissolved in 1031, leading to the emergence of smaller, rival kingdoms known as taifas (these included the Taifa of Cordoba, Taifa of Seville, Taifa of Zaragoza, Taifa of Valencia, Taifa of Dénia, Taifa of Almeria, Taifa of Granada, Taifa of Malaga, Taifa of Toledo, Taifa of Badajoz, Taifa of Tortosa,…)

These kingdoms were often ethnically and politically diverse and frequently sought help from Christian kingdoms in the north or Berber dynasties in North Africa.

The Almoravid and Almohad Dynasties (1086–1212)

To counter the Christian Reconquista, the taifa rulers invited the Almoravids (a Berber Muslim dynasty) from North Africa. They unified Al-Andalus but imposed strict Islamic rule.

The Almohads, another North African dynasty, succeeded the Almoravids in the 12th century. They brought further centralization and built landmarks like the Giralda in Seville.

Decline and the Reconquista (1212–1492)

After the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212, Christian forces rapidly advanced into Muslim territory.

By the 13th century, only the Kingdom of Granada, ruled by the Nasrid dynasty, remained as a Muslim stronghold. Granada flourished culturally, with the construction of the Alhambra palace.

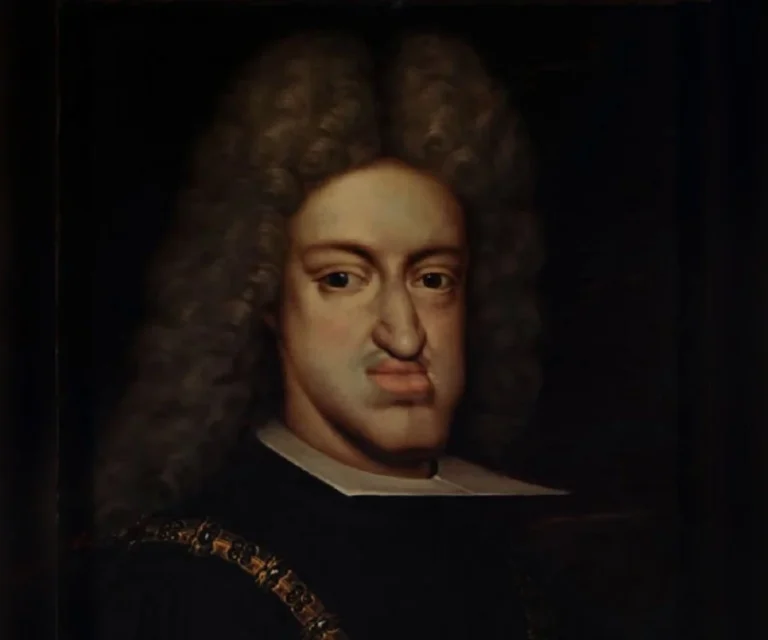

In 1492, the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, conquered Granada, ending Muslim rule in Spain.