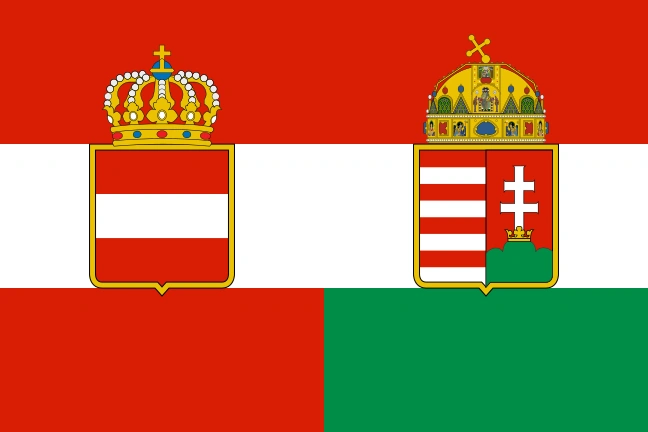

Austria-Hungary, also known as the Austro-Hungarian Empire or the Dual Monarchy, was a major political entity in Central Europe. This multinational empire was one of the most complex and influential states of its time, balancing internal diversity with external pressures.

Formation of Austria-Hungary (1867)

The Dual Monarchy emerged from the ashes of Austria’s defeat in the Austro-Prussian War (1866). To stabilize its realm, Emperor Franz Joseph I negotiated the Ausgleich, which created a dual structure:

- The empire was split into two semi-independent entities: the Austrian Empire (Cisleithania) and the Kingdom of Hungary (Transleithania).

- Each had its own constitution, parliament, and government, but they shared a common monarch, foreign policy, military, and financial system.

The compromise appeased Hungarian nationalists but left many other ethnic groups, such as the Czechs, Poles, Croats, and Serbs, dissatisfied. This marked the beginning of a constant struggle to maintain unity in a diverse empire.

Structure of the Dual Monarchy

Emperor-King: The monarch of Austria-Hungary held the titles of Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary (reigned by Franz Joseph I for most of the empire’s existence).

Austro-Hungarian Ministerial Council (Gemeinsamer Ministerrat): The governing body for joint affairs of Austria-Hungary, including foreign policy, military strategy, and overseeing Bosnia and Herzegovina. Comprised of the joint ministers, the prime ministers of Austria and Hungary, and presided over by the Emperor-King.

Austrian Parliament (Reichsrat): The bicameral parliament of Cisleithania (the Austrian Empire). It consisted of an Upper House (Herrenhaus) and a Lower House (Abgeordnetenhaus), dealing with domestic legislative matters in Austrian-controlled regions.

Hungarian Parliament (Országgyűlés): The legislative body of Transleithania (the Kingdom of Hungary). It was composed of two chambers: the Upper House (Főrendiház) and the Lower House (Képviselőház), managing Hungary’s domestic affairs and promoting Hungarian national interests.

Austro-Hungarian Foreign Ministry (Gemeinsames Außenministerium): Responsible for the empire’s foreign relations, diplomacy, and treaties. Headquartered in Vienna, it served both Austria and Hungary under the direct authority of the Emperor-King.

Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War (Gemeinsames Kriegsministerium): Managed the empire’s unified military forces, including the K.u.K. Army (Imperial and Royal Army) and the navy.

Austro-Hungarian Ministry of Finance for Joint Affairs (Gemeinsames Finanzministerium): Oversaw the budget for shared expenditures like the military and foreign affairs. This ministry did not interfere with the separate finances of Austria and Hungary.

Imperial Court (Reichsgericht): A judicial body that handled disputes related to constitutional matters or conflicts between Austria and Hungary, providing a mechanism for resolving intergovernmental issues.

Economic Growth and Industrialization

In the late 19th century, Austria-Hungary experienced significant economic development, and by 1910, Austria-Hungary was the fourth-largest industrial power in Europe.

Industrialization: Major cities like Vienna, Budapest, and Prague became industrial hubs. Steel mills, and factories proliferated, modernizing the empire. Railroads expanded dramatically, connecting rural areas to urban centers and facilitating trade across the empire. By 1914, Austria-Hungary had one of the densest railway networks in Europe. The empire exploited its coal, iron, and oil resources, particularly in regions like Bohemia (modern-day Czech Republic) and Galicia (modern-day Poland and Ukraine).

Trade and Tariffs: The two halves of the empire were linked by a common customs union, which facilitated free trade within the empire’s borders. Key exports included machinery, textiles, and agricultural products. Austria-Hungary’s position in Central Europe made it a critical trading partner for Germany, Italy, and the Balkans. The empire’s primary seaport became Trieste, connecting Austria-Hungary to global markets and playing a vital role in maritime trade.

Urbanization: Cities like Vienna, Budapest, Prague, and Lviv grew into bustling economic hubs. The empire’s population grew from approximately 36 million in 1867 to over 50 million by 1914.

Agriculture: The Backbone of Hungary: Hungary remained a predominantly agricultural economy throughout the empire’s existence.

Banking and Financial Systems: The Austro-Hungarian Bank, established in 1878, served as the empire’s central bank, issuing currency and stabilizing the economy. Vienna was the financial capital, hosting major banks that financed industrialization and trade. In rural Hungary, limited access to credit hindered small farmers and entrepreneurs, perpetuating economic inequality.

Nationalism and Ethnic Tensions

Austria-Hungary was a mosaic of ethnicities, languages, and religions. The empire’s population included Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Ukrainians, Romanians, Croats, Serbs, Slovenes, and Italians. As a result, the empire’s parliament (Reichsrat) often faced gridlock due to ethnic divisions, and compromises between groups were fragile.

Culture in Austria-Hungary

Prominent Authors:

- Franz Kafka: Known for his existential and modernist works, such as The Metamorphosis.

- Arthur Schnitzler: Explored themes of psychology and morality in Viennese society.

- Gyula Krúdy: Captured the essence of Hungarian rural and urban life in his fiction.

- Mór Jókai: Renowned novelist of Hungarian Romanticism, best known for The Man with the Golden Touch and historical fiction.

- Stefan Zweig: Known for his novellas (The World of Yesterday), essays, and biographies, capturing the cultural essence of the late Habsburg era.

- Karl Kraus: Satirist and critic, editor of Die Fackel, known for his incisive commentary on Viennese culture and society.

- Alois Jirásek: Historical novelist known for his works like Old Czech Legends, chronicling Czech history and folklore.

Classical and Operatic Traditions: Composers like Johann Strauss II popularized the Viennese waltz, while Gustav Mahler and Anton Bruckner pushed symphonic music to new heights. Franz Liszt and Béla Bartók blended Hungarian folk traditions with classical forms. Ethnic communities fostered their own musical traditions, such as Czech composers Bedřich Smetana and Antonín Dvořák, who celebrated their national heritage.

Visual Arts and Architecture: The Vienna Secession (founded in 1897) challenged traditional art styles, with artists like Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele creating groundbreaking works that reflected modernist and Symbolist sensibilities. Hungarian artists like Miklós Zichy and László Paál contributed to Romanticism and Realism. Vienna’s Ringstraße became a showcase of grandiose architectural styles, including Neoclassicism, Gothic Revival, and Baroque Revival, while Budapest’s Parliament Building and Chain Bridge exemplified Hungarian architectural achievements.

Science in Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary was a center of scientific innovation, contributing significantly to fields such as medicine, physics, mathematics, and natural sciences. Its institutions, universities, and academies fostered a vibrant intellectual atmosphere. Many scientific advancements were driven by the empire’s cosmopolitan population, encompassing diverse ethnicities and languages, and the support of Emperor Franz Joseph I, who promoted education and research.

Ignaz Semmelweis (1818–1865): Hungarian physician known as the “savior of mothers” for pioneering antiseptic methods to prevent puerperal fever.

Gregor Mendel (1822–1884): Czech-German friar and biologist who founded the field of genetics through his work on inheritance patterns in pea plants.

Carl von Rokitansky (1804–1878): Austrian pathologist who developed the Rokitansky method of autopsy and advanced the understanding of diseases.

Theodor Billroth (1829–1894): Pioneer in modern abdominal surgery, including the first successful gastrectomy.

János Szentágothai (1912–1994, Hungarian): Neuroscientist who mapped the functional anatomy of the brain.

Erwin Schrödinger (1887–1961): Austrian physicist and Nobel laureate, famous for Schrödinger’s equation and contributions to quantum mechanics.

Ludwig Boltzmann (1844–1906): Physicist who formulated statistical mechanics, providing insights into thermodynamics and entropy.

Christian Doppler (1803–1853): Physicist who discovered the Doppler effect, explaining changes in frequency relative to motion.

Ernst Mach (1838–1916): Physicist and philosopher, known for his work on supersonic motion and influence on Einstein’s relativity.

Kálmán Kandó (1869–1931): Hungarian engineer, pioneer of electric railway systems and the development of the phase converter.

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939): Austrian neurologist and founder of psychoanalysis, transforming the understanding of the human psyche.

Periodization of Austria-Hungary (1867–1918)

1867: Austro-Hungarian Compromise (Ausgleich) establishes the Dual Monarchy, splitting the empire into Austria (Cisleithania) and Hungary (Transleithania), each with its own parliament and government.

1867: Franz Joseph I crowned King of Hungary in Budapest.

1868: Croatian-Hungarian Settlement grants limited autonomy to Croatia within the Kingdom of Hungary.

1869: Modernization efforts begin, including constitutional and infrastructure reforms. First stock exchange in Vienna established, signaling the rise of modern financial institutions.

1873: Vienna Stock Market Crash (Gründerkrach) triggers an economic downturn but also leads to industrial consolidation.

1878: Congress of Berlin grants Austria-Hungary the right to occupy and administer Bosnia and Herzegovina, increasing its influence in the Balkans.

1882: Austria-Hungary joins the Triple Alliance with Germany and Italy, solidifying its position in European geopolitics. Establishment of the Austro-Hungarian Bank as a central bank to oversee monetary policy and issue the currency.

1883: Railways and industrialization expand rapidly, modernizing the economy and integrating rural regions with urban centers. The Orient Express route through Austria-Hungary is completed, boosting international trade and tourism.

1888: New oil reserves discovered in Galicia (modern-day Poland/Ukraine), making the region one of the largest oil-producing areas in Europe.

1889: Ethnic tensions escalate as Czech, Polish, and South Slavic nationalist movements grow.

1890s: Expansion of Bohemia’s industrial sector, making it a center for textiles, machinery, and glass production.

1899: Electrification begins in major cities like Vienna and Budapest, heralding a new era of industrial modernization.

1902: Completion of the Trans-Leitha Railway further integrates Austria and Hungary’s economic activities.

1905: Political crises in Hungary lead to demands for greater autonomy and a more independent role within the empire.

1907: Universal male suffrage introduced in Austria, increasing political participation but also amplifying ethnic and class divisions.

1908: Austria-Hungary formally annexes Bosnia and Herzegovina, provoking outrage in Serbia and among Slavic populations.

1912–1913: Balkan Wars destabilize the region, with Serbia emerging as a powerful Slavic state, intensifying tensions with Austria-Hungary.

1914: Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo by a Bosnian Serb nationalist sparks the July Crisis, leading to Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war on Serbia.

1914–1918: Austria-Hungary fights as part of the Central Powers alongside Germany in World War I, but suffers defeats and internal strife:

1916: Death of Emperor Franz Joseph I; Charles I becomes Emperor.

1917: Widespread famine, strikes, and political unrest weaken the empire.

October 1918: Hungary dissolves its ties with Austria, and other regions secede.

November 1918: Austria-Hungary formally ceases to exist with the signing of armistices.