Predynastic Egypt refers to the period before the establishment of the first unified Egyptian state around 3100 BC, a time that laid the foundation for one of the most enduring civilizations in human history. Spanning several millennia, this era saw the gradual development of key cultural, technological, and social advancements that would eventually define ancient Egyptian society. This article delves into the various Predynastic cultures of Egypt. By examining key archaeological sites, technological innovations, and burial practices, we can better understand how each of these cultures contributed to the social and political developments that led to the rise of the early dynastic period.

The Paleolithic Period of Predynastic Egypt (c. 2.5 million years ago – 22,500 BC )

Oldowan culture (2.5 million years ago – 1.5 million years ago)

The Oldowan culture is one of the earliest recognized stone tool cultures, dating back to around 2.5 million years ago. It represents the most basic form of tool-making, developed by early human ancestors, such as Homo habilis and other early hominins, during the Lower Paleolithic period. In Egypt, evidence of the Oldowan industry is primarily found in the Nile Valley and Western Desert regions.

Acheulean culture (400,000–130,000 BC)

The youngest Acheulean sites in Egypt date back to around 400,000 to 300,000 years ago, primarily located in the Northeast Sahara and Western Desert regions. One of the most notable findings from this period is a rare Acheulean handaxe, which was discovered nine miles northwest of the city of Naqada.

Wadi Halfa culture (c. 100,000 BC)

The Wadi Halfa culture is notable for its early evidence of semi-permanent dwellings in ancient Egypt, which dates back to around 100,000 BC. Discovered by archaeologist Waldemar Chmielewski near the southern border of Egypt, close to Wadi Halfa in Sudan, these findings provide valuable insights into the lifestyle of prehistoric people in the region.

At the Arkin 8 site, Chmielewski uncovered some of the oldest known structures in Egypt, revealing a fascinating glimpse into the living conditions of the time. The structures found at the site are oval depressions, approximately 30 cm deep and 2 × 1 meters across. These depressions were lined with flat sandstone slabs, which served as tent rings, likely supporting dome-like shelters made of skins or brush. These shelters were portable and could easily be assembled and disassembled, making them ideal for mobile hunter-gatherers who required flexibility in their living arrangements.

Khormusan culture (42,000–18,000 BC)

The Khormusan culture was a Paleolithic archaeological industry that existed in Nubia (southern Egypt and Sudan) and dates back to between 42,000 and 18,000 BC. The Khormusan people were skilled toolmakers, crafting tools not only from stone but also from animal bones and hematite (an iron oxide). One of the most notable technological developments of the Khormusan culture was the creation of small arrowheads. It was succeeded by other regional cultures, notably the Gemaian culture.

Aterian culture (40,000–20,000 BC)

The Aterian culture is a Middle Stone Age archaeological culture that emerged in North Africa around 145,000 years ago and persisted until about 20,000 years ago. Originally centered in the Maghreb, the Aterian culture spread across vast regions of North Africa. It reached Egypt around 40,000 BC, where it was notably present in the Kharga Oasis in the Western Desert.

The Mesolithic Period of Predynastic Egypt (c. 22,500–6,000 BC)

Halfan culture (22,500-22,000 BC)

The Halfan culture represents one of the significant Late Epipalaeolithic industries that flourished in the Upper Nile Valley, primarily in northern Sudan, around 22.5 to 22.0 ka cal BP (approximately 22,500 to 22,000 years ago). Emerging after the Khormusan culture, the Halfan culture is thought to have developed as a continuation and adaptation of the earlier Khormusan traditions.

The Halfan people primarily relied on large herd animals, alongside the continuation of fishing practices that had been characteristic of the Khormusan period. Their diet and subsistence strategies suggest a more sedentary way of life compared to their predecessors, with greater concentrations of artifacts indicating that they were not bound to seasonal wandering, but instead settled in areas that offered access to abundant resources.

The Halfan industry is characterized by the production of distinct tools, including Halfa flakes, backed microflakes, and backed microblades, which were central to their daily activities and survival strategies.

Kubbaniyan culture (17,000-15,000 BC)

The Kubanniyan culture is a parallel industry to the Halfan culture. It was located in Egypt, specifically at the Wadi Kubbaniya site. This culture belongs to the Late Epipalaeolithic period and shares many similarities with the Halfan industry. At Wadi Kubbaniya, traces of barley were discovered, which initially led to the assumption that the site marked the beginning of agricultural practices. However, further investigation has revealed that the barley was not cultivated but rather wild, which suggests that this was not an early form of agriculture, but instead an example of humans utilizing naturally available plant resources.

Significant finds from the Wadi Kubbaniya site include grinding stones, fish bones, bird bones, mammal bones, charcoal, and backed bladelets, all of which offer insights into the diet and technological practices of the Kubannian people. Interestingly, charred bits of human feces were also uncovered at the site, which likely came from infants. This discovery is notable because it provides direct evidence of plant consumption by humans during this period.

Sebilian culture (13,000-10,000 BC)

The Sebilian culture is an archaeological culture that emerged around 13,000 BC and disappeared by approximately 10,000 BC. This culture, sometimes referred to as the Esna culture due to its association with the Esna region in Egypt, is considered part of the Late Epipalaeolithic phase. It represents a period of significant change in the prehistoric societies of Egypt, particularly in terms of subsistence strategies and settlement patterns.

The people of the Sebilian culture were semi-sedentary, likely living near the Nile River, where they exploited the rich resources of the region. Pollen analysis from archaeological sites indicates that the Sebilian people were gathering grains, although there is no evidence of domesticated crops, which suggests that they practiced a form of wild grain collection rather than agriculture. This reliance on wild plant resources indicates a transition toward a more sedentary lifestyle. Dietary evidence from the Sebilian culture further reflects their semi-sedentary existence. The primary sources of food were fish, which was abundant in the Nile River, along with more occasional consumption of crocodile and turtle.

Qadan culture (13,000-9,000 BC)

The Qadan culture, which spanned from around 13,000 to 9,000 BCE, represents an important period in the prehistoric development of the Nile Valley, particularly in the region of Nubia.

One of the most distinctive features of the Qadan culture was its unique approach to food gathering. While the Qadan people continued to rely on hunting, they also developed a method of systematic plant gathering that involved harvesting wild grasses and grains. Although these plants were not cultivated in organized rows, the Qadan people made deliberate efforts to water, care for, and harvest local plant life, suggesting an early form of plant management and domestication. Large numbers of grinding stones and blades have been found at Qadan sites, with some exhibiting a glossy film of silica, which likely resulted from cutting grass stems or processing wild plant materials.

The Qadan culture is also notable for its evidence of conflict. The discovery of numerous fatal wounds on the skeletons found in the Jebel Sahaba cemetery, located near the Sudanese border along the Nile, indicates that this society experienced significant inter-tribal violence or possibly invasions. Around 40 percent of individuals buried at the site show signs of projectile wounds, providing evidence of the intense social strife and warfare.

The Neolithic Period of Predynastic Egypt (c. 6,000–4,500 BC)

The Faiyum B, or Qarunian culture (6500–5190 BC)

Predating the Faiyum A culture, the Faiyum B, or Qarunian culture reflects an Epipalaeolithic or Mesolithic tradition. Dated to approximately 6500 to 5190 BC, the Qarunian culture, centered around Lake Qarun, is notable for its lack of pottery. Instead, it features microlithic blades, plain blades, gouges, and arrowheads, suggesting possible interactions with the Sahara.

The Faiyum A culture (5600–4400 BC)

The Faiyum A culture, dating from about 5600 to 4400 BC, represents one of the earliest farming societies in the Nile Valley. This culture’s development was significantly influenced by the environmental pressures of desert expansion, which forced early inhabitants to adopt more sedentary lifestyles around the fertile Nile. The Faiyum A culture is distinguished by the production of concave base projectile points and pottery, marking an advancement in tool-making and domestic activities.

Merimde culture (5000–4200 BC)

The Merimde culture, closely linked to the Faiyum A culture and influenced by the Levant, thrived around the settlement of Merimde Beni Salama, located in the West Delta of the Nile, approximately 45 kilometers northwest of Cairo. This culture was primarily agrarian, though evidence suggests that fishing and hunting supplemented their diet. The settlement comprised small, round or elliptical huts constructed from wattle and reed, reflecting a modest yet organized community structure.

Merimde pottery is distinctive for its lack of “rippled marks,” a feature common in other contemporary pottery. The burial practices of the Merimde culture were particularly unique. Unlike the separate cemetery areas common in Upper Egyptian Predynastic and later Dynastic Egypt, the dead were interred within the settlement itself. They were placed in flexed positions in oval pits, devoid of grave goods or offerings.

Tasian culture (4500–3100 BC)

The Tasian culture, emerging around 4500 BC, is possibly one of the oldest-known Predynastic cultures in Upper Egypt. This culture is named after the burials found at Deir Tasa, situated on the east bank of the Nile between Asyut and Akhmim. It is particularly notable for producing the earliest examples of black-topped pottery, a distinctive type of red and brown pottery with a black-painted upper section. This early ceramic innovation would influence subsequent Egyptian pottery styles.

Archaeological excavations of Tasian burials have revealed numerous skeletons, which are generally taller and more robust than those from later predynastic periods. In this respect, the physical characteristics of Tasian skeletons are closely aligned with those found in the Merimde culture, indicating possible connections or similarities between these early groups.

Badarian culture (4400–4000 BC)

he Badarian culture represents the earliest direct evidence of agriculture in Upper Egypt and is named after its discovery at El-Badari, located in the Asyut Governorate. This culture, thriving around 4400 to 4000 BC, marked a significant shift towards a more settled lifestyle based on agriculture, fishing, and animal husbandry. Badarian communities cultivated wheat, barley, lentils, and tubers, with pits found at archaeological sites likely serving as granaries. They also domesticated cattle, sheep, goats, and dogs, which were sometimes given ceremonial burials.

The Badarian economy demonstrated a sophisticated level of resource management and trade. Basalt vases found at Badarian sites suggest trade links with the Delta region or northwest territories, while shells from the Red Sea and possibly turquoise from Sinai indicate extensive trade networks. A four-handled pot of hard pink ware hints at a Syrian connection, reflecting the wide-ranging interactions of the Badarian people.

In terms of burial practices, the Badarian culture displayed rituals that would later influence Dynastic Egypt. The deceased were wrapped in reed matting or animal skins and buried in pits, often positioned with their heads to the south, facing west—the direction associated with the land of the dead in later Egyptian beliefs. Graves were sometimes accompanied by female mortuary figures carved from ivory, as well as personal items like flint tools, amulets, and jewelry made of ivory, quartz, or copper.

Naqada culture (4000–3000 BC)

The Naqada culture, spanning from approximately 4000 to 3000 BC, represents a key Chalcolithic Predynastic culture of ancient Egypt, named after the town of Naqada in the Qena Governorate. This culture evolved through three distinct phases: Naqada I, Naqada II, and Naqada III, each marked by unique developments in pottery, trade, and social complexity.

- Naqada I (also called Amratian culture) (c. 4000–3650 BC) was characterized by black-topped and painted pottery. During this phase, the Naqada culture established trade connections with Nubia, the Western Desert oases, and the Eastern Mediterranean, importing obsidian from Ethiopia. The pottery from this period often featured decorative motifs and served both cultural and utilitarian purposes.

- Naqada II (also called Gerzean culture) (c. 3650–3300 BC) saw the expansion of the culture throughout Egypt, with the introduction of marl pottery and early metalworking. Pottery designs became more intricate, incorporating floral motifs and depictions of people. Some of these designs, such as griffins and serpent-headed panthers, suggest early Mesopotamian influence, linking the Naqada culture with the broader ancient world.

- Naqada III (c. 3300–2900 BC), overlapping with the Protodynastic Period, is marked by the appearance of more elaborate grave goods and the emergence of the first Pharaohs. Cylindrical jars and early forms of writing began to appear, reflecting increased social complexity and the centralization of power. This phase represents a significant cultural transformation, leading to the rise of the dynastic state.

El Omari culture (4000–3100 BC)

The El Omari culture, situated near modern-day Cairo, represents an important phase in the pre-dynastic development of ancient Egypt. Archaeological evidence from the El Omari settlement, which dates from around 4000 BC to the Archaic Period (3100 BC), reveals a modest lifestyle centered around small huts. While the actual structures have not survived, postholes and pits provide clues to their construction and layout. The culture is characterized by its simple, undecorated pottery, indicating functional rather than aesthetic use. The El Omari people relied on a range of stone tools, including small flakes, axes, and sickles, which were essential for their daily activities and subsistence. Notably, metalworking was not yet part of their technological repertoire.

Maadi culture (4000–3500 BC)

The Maadi culture, predominantly known from the archaeological site near Cairo and the site of Buto, extended across the Nile Delta to the Faiyum region. This culture marked a significant advancement in architecture and technology. Maadi’s settlements featured small, partially subterranean huts that provided practical living spaces adapted to the environment.

In terms of material culture, the Maadi people continued the tradition of using simple, undecorated ceramics, reflecting a focus on functionality. However, their technological advancements are evident in the introduction of copper tools, including copper adzes, signifying an early stage of metallurgy. The pottery included black-topped red pots, indicative of cultural exchange with the Naqada sites in the south. Additionally, the presence of imported vessels from Palestine and the use of black basalt stone vessels highlight the Maadi culture’s extensive trade networks.

Burial practices in the Maadi culture involved interring the dead in cemeteries, albeit with minimal burial goods, suggesting a community that placed limited emphasis on elaborate funerary rites.

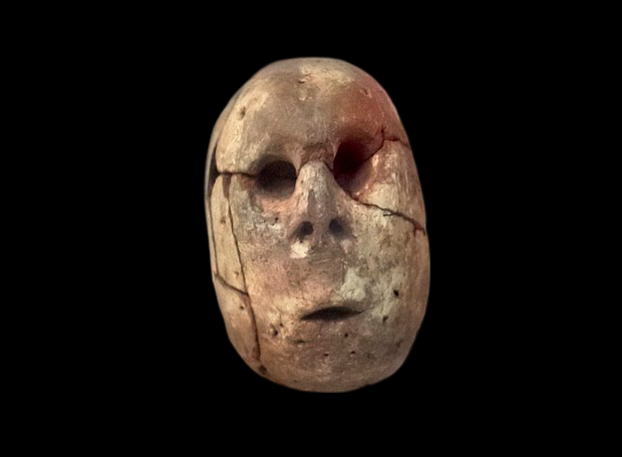

Cover photo: kairoinfo4u, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Other related articles:

1 thought on “Cultures of Predynastic Egypt: Unearthing the Foundations of a Great Civilization”

Comments are closed.