The Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) marked a transformative era in the development of China’s education system, laying the foundation for many of the principles and structures that would shape Chinese society for centuries to come. During this period, education evolved from a loosely organized, elitist pursuit into a more structured and accessible system that emphasized the importance of moral cultivation, governance, and cultural refinement. Central to this transformation was the establishment of government-sponsored schools, the formalization of Confucianism as the state ideology, and the gradual expansion of educational opportunities from the central capital to local communities.

Content of Education

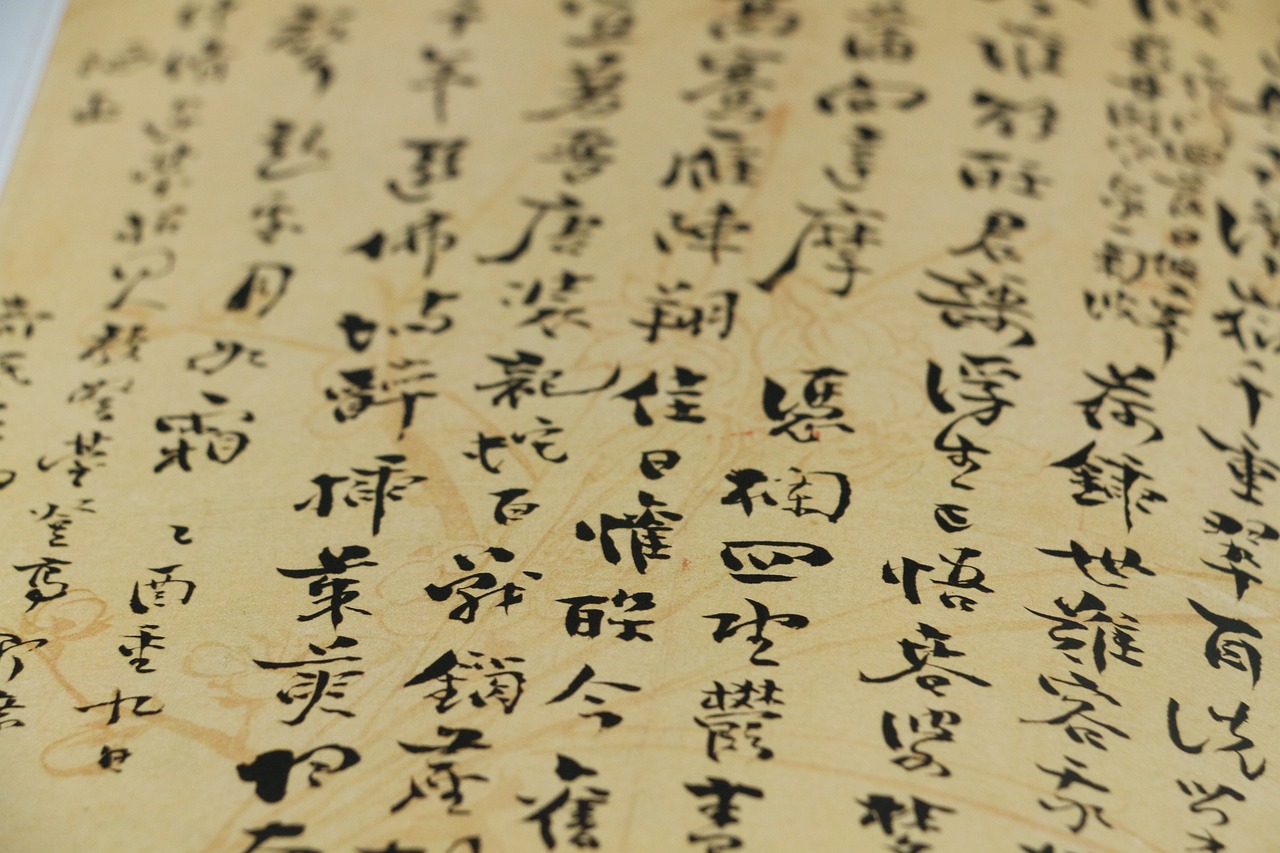

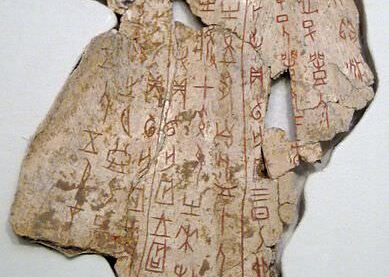

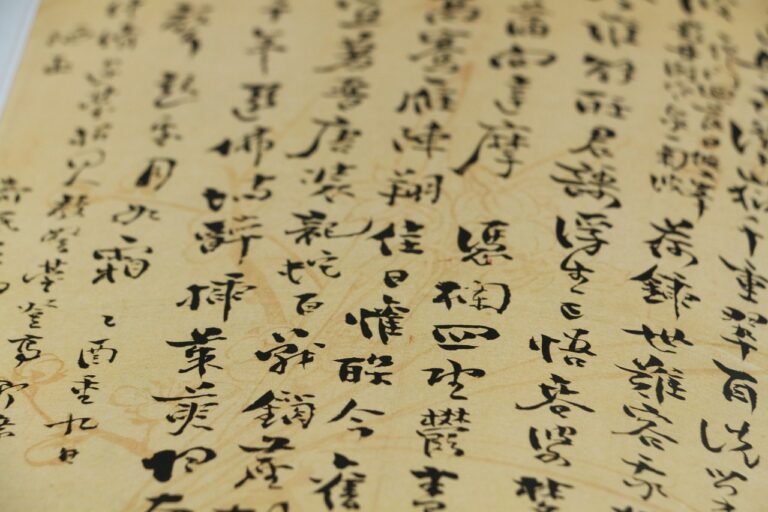

The Han dynasty adopted Confucianism as the guiding philosophy of governance, which emphasized moral education, social harmony, and respect for hierarchy. Education focused heavily on the five Confucian Classics that encapsulate Confucian ideals, intertwining ethics, history, culture, and governance into a unified framework that has influenced Chinese thought for centuries. The five Confucian Classics include:

Analects: a collection of sayings and dialogues attributed to Confucius and his disciples, focusing on personal ethics, morality, and governance. It emphasizes the cultivation of virtues such as benevolence (ren), propriety (li), and righteousness (yi), asserting that the moral character of individuals, particularly rulers, is essential for a harmonious society. The text’s aphoristic structure serves as a guide for ethical living and good leadership, making it central to Confucian education.

Book of Songs: a compilation of 305 poems from the Zhou Dynasty, explores themes of love, nature, politics, and ancestral worship. Its folk songs, odes, and hymns offer a glimpse into early Chinese society, reflecting both everyday emotions and formal court life. The collection underscores Confucian values through allegory and moral lessons

Book of Documents: a repository of speeches, proclamations, and historical records from ancient Chinese rulers and ministers. It presents a vision of governance based on virtue, the Mandate of Heaven, and moral responsibility. Through its accounts of virtuous leadership and the consequences of tyranny, the text serves as both a historical chronicle and a manual for ethical statecraft, reinforcing the idea that good governance depends on moral integrity.

Book of Rites: a detailed exploration of rituals, social norms, and proper behavior that promote harmony in society. It outlines ceremonial practices for events like weddings, funerals, and ancestral worship, while also addressing the roles and responsibilities of individuals within the social hierarchy.

Spring and Autumn Annals: a concise chronicle of the state of Lu, traditionally edited by Confucius. Its entries on political, military, and social events from 722 BCE to 481 BCE are imbued with moral judgments, illustrating the consequences of virtuous or unethical actions.

School System

During the Han Dynasty, the education system comprised state schools and private schools, with state schools achieving the highest level of development.

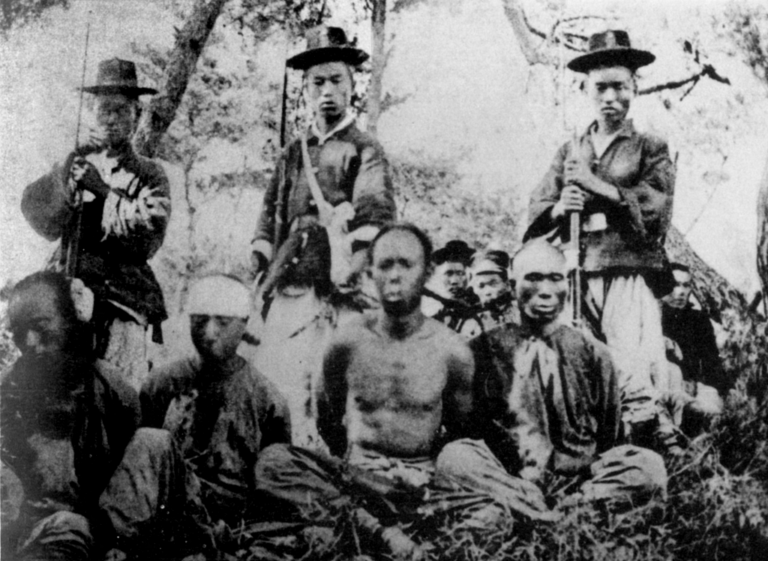

The Imperial Academy (Taixue, 太学) was the highest educational institution and educational administrative department in Han China. It was founded by Emperor Wu (156–87 BCE) of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE) in 124 BC. The institution appointed teachers, known as boshi (comparable to modern-day doctors), selected from the ranks of highly skilled and distinguished officials. Initially, only 55 students were admitted to the Imperial Academy. By 8 BCE, the Academy’s enrollment had grown to three thousand students.During the reign of Emperor Shun (115–144 CE), the Imperial Academy flourished, with enrollment of boshi disciples—comparable to modern university students—surpassing 30,000.

In 3 CE, during the reign of Emperor Ping of the Han Dynasty, China saw the establishment of its first comprehensive, nationwide government school system. This initiative marked a significant advancement in the standardization and accessibility of education. At its center was the Taixue (Imperial Academy), located in the capital city of Chang’an, which served as the highest educational institution for training future scholars and government officials.

To extend education beyond the elite circles of the capital, the system also included schools set up at the prefectural level and in the principal cities of smaller counties. These local institutions aimed to provide a foundational education, focusing on Confucian classics, ethics, and governance, to prepare students for further study and possible entry into the civil service. Local state schools evolved steadily, and by 3 CE, a structured feudal educational system had been formally established in China.

In 176 CE, Emperor Ling of the Han Dynasty established China’s first specialized school, marking a significant milestone in the development of specialized education. This institution was dedicated to the study and refinement of prose, calligraphy, and painting, disciplines that were highly esteemed in Chinese culture. The specialized school of Emperor Ling was comparable to modern cultural and arts colleges, enrolling more than a thousand students.

Examinations

During the Han Dynasty, there was no formal system for evaluating students’ abilities or qualifications. Instead, talent identification relied heavily on informal methods, with observation being the most common practice. Government officials would assess individuals based on their perceived intelligence, behavior, and capabilities in daily life. Those deemed promising were recommended to higher authorities for potential appointments. The examination system was first administered in 605 CE during the Sui dynasty and remained a cornerstone of Chinese governance and society for over a millennium, enduring with few interruptions until its eventual abolition in 1905 CE.

2 thoughts on “Education System during the Han Dynasty”

Comments are closed.