The Chinese language has a documented history spanning over three millennia, making it one of the world’s longest continuously used written languages. It has evolved through several distinct epochs, reflecting social, political, and cultural changes. Below is an overview of the history of the Chinese language, divided into major historical periods.

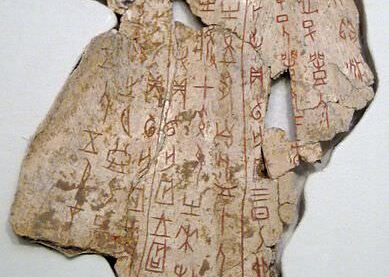

Pre-Classical Chinese (Before 1250 BCE)

The earliest written Chinese appears in the form of oracle bone inscriptions from the Shang dynasty (c. 13th century BCE) in modern Anyang, Henan. These inscriptions provide the first direct evidence of Sinitic languages, a branch of the larger Sino-Tibetan language family. Linguists generally agree that the Sinitic languages share a common ancestor with Tibeto-Burman languages, though the exact classification within Sino-Tibetan remains debated.

Archaic Chinese (11th–7th Century BCE)

During the early and middle Zhou dynasty (11th–7th centuries BCE), Archaic Chinese (also known as Old Chinese) was the common language of the period. Texts from this era include inscriptions on bronze artifacts, as well as classical literary works such as:

- The Shijing (Book of Songs), a collection of ancient poetry

- The Shujing (Book of Documents), one of China’s earliest historical records

- Portions of the Yijing (Book of Changes), a foundational text in Chinese philosophy

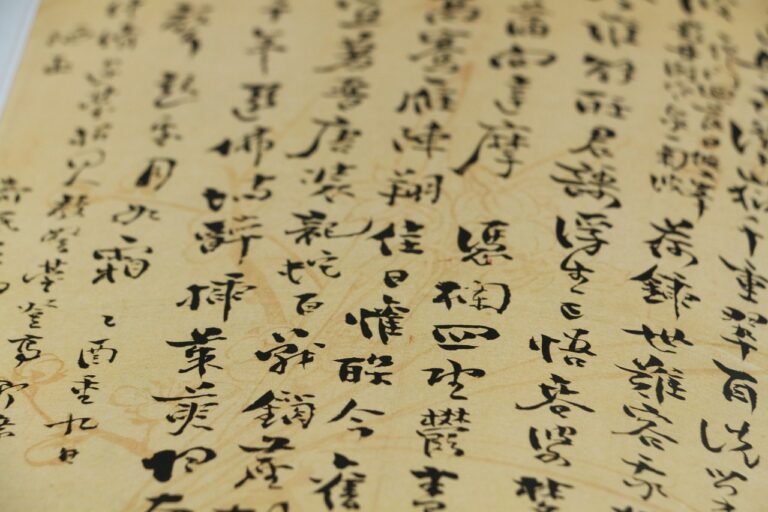

Reconstruction of Old Chinese began during the Qing dynasty, when scholars analyzed phonetic components in Chinese characters to infer historical pronunciation. Unlike modern Chinese, Old Chinese contained consonant clusters and lacked tonal distinctions. It also had elements of inflection, making its grammar more complex than later forms of the language. As spoken Chinese continued to evolve, different regional dialects emerged. The geography of China played a key role—while the North China Plain encouraged linguistic unity, the mountains and rivers of southern China led to greater diversity.

Classical Chinese (7th century BCE–7th Century CE)

Classical Chinese was largely composed of single-syllable words, with each written character representing an independent word. While Chinese was mostly analytic (meaning it didn’t use inflections like many European languages), it did have some ways of forming new words.

One way was by adding small sound elements, called affixes, to change meaning. Over time, these affixes led to changes in pronunciation. For example, a suffix that likely sounded like -s in Old Chinese later influenced tones in Middle Chinese and modern dialects.

Another common change in pronunciation involved the first sound of words. Some words started with a voiced sound (like “b” or “d”), while others had voiceless versions (like “p” or “t”). These shifts likely indicated whether a verb was active or passive, but scholars still debate which version was the original. Over time, this distinction disappeared in most modern Chinese dialects, though traces remain in pronunciation and word meanings.

Middle Chinese (7th–10th Century CE)

Middle Chinese was the language spoken during the Sui, Tang, and Song dynasties. It can be divided into:

- Early Middle Chinese (7th century CE)

- Late Middle Chinese (10th century CE)

Reconstruction of Middle Chinese pronunciation is based on:

- Rhyme books, which preserved pronunciation patterns

- Modern dialect comparisons, since some southern dialects retain archaic features

- Foreign transliterations, such as Chinese loanwords recorded in Sanskrit and Tibetan

Middle Chinese had a strong influence on languages such as Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese, all of which borrowed vocabulary and writing systems from Chinese. The period also saw the early development of Mandarin, Cantonese, Wu (Shanghainese), and Min dialects.

Modern Chinese (10th Century CE–Present)

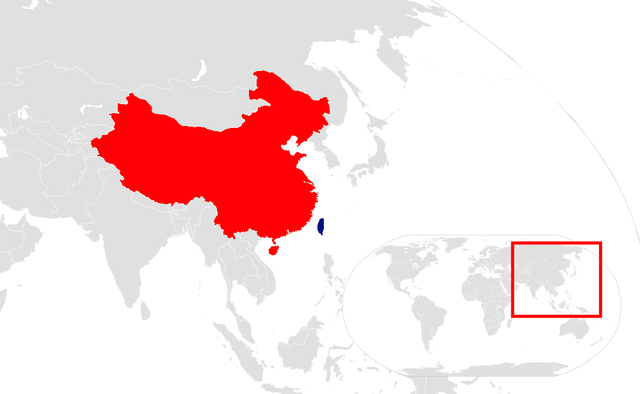

By the 10th century, spoken Chinese had developed into distinct regional varieties. The Mandarin dialects, spoken across northern China, became especially influential due to geography—the North China Plain allowed for greater linguistic cohesion.

In contrast, southern China, with its mountainous terrain and numerous rivers, retained a greater diversity of dialects. Many areas did not speak Mandarin until the 12th century, when northern migrants repopulated Sichuan following a devastating plague.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the official government language was based on Nanjing Mandarin. However, many regions continued to speak their local dialects. The Qing emperors attempted to standardize Mandarin through Orthoepy Academies, but these efforts had little success.

By the late 19th century, Beijing Mandarin replaced Nanjing Mandarin as the court standard. However, among the general population, a single standard form of Mandarin did not exist. Southern Chinese communities continued using their regional languages in everyday life.

The 20th century marked a turning point. In mainland China and Taiwan, elementary schools began systematically teaching Standard Chinese (Mandarin), ensuring that younger generations grew up speaking a common language. However, in Hong Kong and Macau, which were under British and Portuguese rule at the time, Mandarin was not part of the school curriculum. Instead, Cantonese remained the dominant language for daily communication, business, and education in these regions, as well as in Guangdong and parts of Guangxi.

A major shift in language policy began in 1913 when the Kuomintang (KMT) government attempted to unify pronunciation across different Chinese dialects. They based their new “national language” (Guoyu) on Guanhua, the spoken language of government officials. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), these efforts continued under a new name—Standard Chinese—which was promoted as a tool for national unity.

To further improve literacy, the Chinese government introduced Simplified Chinese characters in 1956, reducing the complexity of traditional writing. This reform made reading and writing easier, especially for those with limited education.

…

Related articles:

Oldest Surviving Languages by First Written Record

Image:

Original image by BabelStone, uploaded by Ibolya Horváth, 25 January 2016. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike.