Inter-Bloc Organizations in the Late Stalin Era: More Than Platforms for East-West Feuds

Ondrej Fiser

PhD, University of Geneva – Switzerland

E-mail: fiserondrej1@gmail.com

Originally published in the Romanian Journal of Historical Studies, Volume VII – Issues, 1-2/2024

Abstract

This article examines the issue of international cooperation on the platform of selected international organizations during the late Stalin era at the beginning of the Cold War, approximately between 1947 and 1953. A number of historians such as Kaplan and Prucha in their monographs highlight the flows of information, capital and technology solely within the Eastern Bloc, but as the newly accessible UN archives in Geneva reveal, even the period of Stalin’s strongly authoritarian rule was characterized by hitherto under-appreciated cross-Curtain ties instrumental in forging diplomatic dialogue, trade and scientific-technical cooperation. The present article analyses these ties on the platform of selected international organizations, namely the UN Economic Commission for Europe and the International Monetary Fund. The selection of these organizations was not arbitrary. Preliminary research of their archival material has outlined their crucial role in the formation of inter-bloc dialogue at the turn of the 1940s and 1950s. The present paper devotes particular attention to the role of Czechoslovakia and its delegates on the above-mentioned platforms. It turns out that it was Czechoslovakia that was able to emerge as an actor mediating and proactively shaping East-West dialogue and different cooperation projects. Although this Central European state was part of the Eastern Bloc, the strong traditional ties of Czechoslovak diplomacy and economy to Western Europe were not completely deconstructed at the beginning of the Cold War, thus enabling Czechoslovakia to become an imaginary bridge between the two halves of the Iron Curtain.

Key words: East-West cooperation, Cold War, international organizations, Economic Commission for Europe, International Monetary Fund, Czechoslovakia, Stalin era.

Introduction

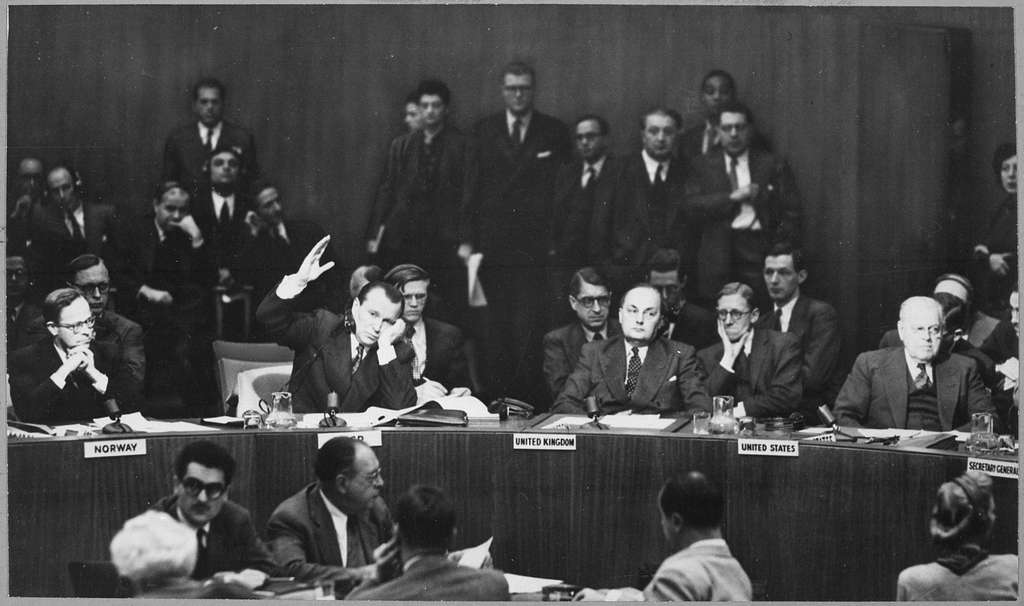

In the middle of the last century, international organizations proved to be an important driving force not only for the development of political-economic ties between partners within individual geopolitical blocs, but also for the intensification of inter-bloc cooperation. This phenomenon is gradually coming under the scrutiny of contemporary historiography, which seeks to deconstruct the concept of the Iron Curtain as impenetrable to the flows of information, capital and people. While many secondary sources not only from the Cold War period but also from the 1990s present the late Stalin era as a period in which the histories of “two independent geopolitical blocs” were unfolding, new currents of contemporary historiography, represented for example by Fava, Lagendijk or Kott, point to the necessity of linking the two narratives into one.1 The appropriateness of this approach is supported by newly accessed archives of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the United Nations (UN), which show that even during the “coldest period” of the Cold War under Stalin, active contacts between the two geopolitical blocs were maintained particularly through selected global organizations.[2]

The aim of this article is to analyze the hitherto marginalized and unrecorded roles of selected international organizations in the development of East-West economic and scientific-technical cooperation at the beginning of the Cold War. The hypothesis here is that organizations such as the IMF or the ILO not only constituted a platform of contact between politico-economically diametrically opposed delegations, but also represented a milieu on which the various tangible outputs of international cooperation were prepared, explored and implemented. The paper also seeks to juxtapose the two conflicting pressures that acted upon the operations of these organizations. On the one hand, especially in the period 1948-1953, the East-West platforms were under strong pressure of politicization efforts from the leadership of both geopolitical blocs, but on the other hand, they also represented a promising haven for the scientific-technical intelligentsia that tried to use them for purely non-political purposes.

The article examines several key organizations and actors of East-West exchanges during the late Stalin era (circa 1947-1953). A particular emphasis is devoted to the UN Economic Commission for Europe (ECE), which acted as a “bridge” across the Iron Curtain throughout the entire Cold War period, facilitating different patterns of flows of goods, capital, experts, and information. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the International Monetary Fund also played a specific role in East-West ties and thus are likewise given limited space within the article. The case study focuses on the role of Czechoslovakia, which in the late 1940s emerged as one of the most active participants in East-West cooperation projects.

The Undeniable Potential of East-West Organizations

Although in general terms the leadership of the member economies of the Council of Mutual Economic Cooperation (CMEA) advocated withdrawal from a number of international organizations at the beginning of the Cold War, limited involvement in selected strategic inter-bloc platforms continued to be encouraged because of their undeniable potential for generating economic growth. The advantages of East-West organizations did not escape the attention of Eastern Bloc economists and historians of the communist period. For instance, some of the benefits of depoliticized UN institutions were analyzed in the 1980s by economic experts, including Kladiva and Hulinský.[3] In the period after the fall of the Iron Curtain, individual East-West cooperation projects on the platform of international organizations were addressed, for example, by Lagendijk and Schipper.[4] However, their studies focused on a narrow profile of the sector of infrastructure and thus did not seek to provide a more comprehensive view of the role of international organizations in the development of socialist economies.

To fill this historiographical gap, new archival fonds of the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), ECE, GATT, IMF and other organizations were analyzed. Reports, studies and internal correspondence from these archives indicate that Czechoslovak, Polish and partly Hungarian cooperation in selected international economic organizations took constructive forms even in the late Stalin era, which was especially true for the years between 1948 and 1950. Although inter-bloc contacts were often maintained also during the escalation of the Cold War in 1951-1952, it must be admitted that the Eastern participation became more passive and politicized.5

The issue of the pull factors for the participation of socialist economies in the platform of East-West organizations in 1947-1953 has not yet been comprehensively analyzed. As the newly accessible documents at the United Nations Library & Archives Geneva reveal, inter-bloc organizations of the UN format were unique in that they brought together government delegations and top experts from both sides of the Iron Curtain on a permanent long-term basis. This characteristic allowed them to develop specific forms of cooperation that could not be implemented through other channels. This was the case of large-scale multilateral projects, for example, in the construction of inter-bloc transport infrastructure or the energy grid. Another potential explanation for their key role was their ability to negotiate international rules in the field of trade, industrial standardization, transport, postal services and other areas of multilateral interest.[5] These advantages of inter-bloc organizations were then reflected in the dynamic approach of both Eastern and Western governments to their work.

Other motives for participating in the work of inter-bloc organizations stemmed from the opportunity to criticize the policies of the other geopolitical bloc and to lobby for the interests of ideologically aligned countries. In particular, politicized organizations with a more general focus, such as ECOSOC, have become a ground for reaching these objectives. Other common platforms in this regard included less technical bodies/sessions within the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), ILO, GATT, IMF, ECE and other organizations. However, as already mentioned, it must be admitted that not all of the activities in international organizations were motivated solely by the opportunity to defend socialist/capitalist ideology and criticize the partners. As already outlined by Nykryn, Lagendijk and Štiková, the Polish, Czechoslovak and Hungarian governments also frequently sought to deepen depoliticized technical forms of inter-bloc cooperation.[6] In this context, socialist delegates were even likely to present and lobby for their own national economic needs and not necessarily only for the interests of the Eastern Bloc as a whole. An analysis of the hitherto understudied correspondence between the Polish and Czechoslovak governments and individual secretariats and delegates on inter-bloc platforms reveals the extent of this cooperation and its key impact on the “convergence” of the two geopolitical blocs. Polish and Czechoslovak participation did not avoid the organization of various study tours, compilation of statistical surveys, joint addressing of scientific-research problems, provision of loans, development of trade, and other forms of depoliticized inter-bloc activities.

This phenomenon was further facilitated by the fact that the complete ideological boycott of certain interbloc platforms by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), complemented by the insufficient capacity of Soviet diplomats, did not allow the Soviet leadership to fully control the approach of other CMEA members to the work of all the international organizations. This, too, proved to be one of the main pull factors for the socialist intelligentsia, which saw in inter-bloc organizations the possibility of constructing its own profitable forms of international cooperation. Archival findings indicate that, for example, cooperation within the Bretton Woods institutions was to a large extent directed by the Czechoslovak government independently of the views of the CPSU. The correspondence of the Czechoslovak Executive Director at the IMF, Bohumil Sucharda, with the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs shows their capacity to follow the political and macroeconomic interests of Czechoslovakia even in ideologically sensitive matters such as West German membership in the Fund.[7] As the UN archives in Geneva, supplemented by the findings of Posejpalová-Kohoutová and Kladiva, show, a pragmatic and proactive approach of the Eastern Bloc was evident in the question of participation in the ECE.[8]

This organization played an important role in the implementation of inter-bloc projects between 1948 and 1950, although it also significantly facilitated international dialogue during the escalation of the Cold War in 1951 and 1952. Reports on the work of the individual ECE committees show that these bodies provided a unique platform where negotiations on Eastern Bloc trade with Western European countries were conducted. This was observable in particular within the Industry and Materials Committee, the Electric Power Committee, the Timber Committee and the Committee on the Development of Trade, where the possibilities of exchanging electricity, forestry equipment, steel, fertilizers, bearings, and other categories of goods were discussed in a depoliticized manner.[9]

Several factors had a major positive impact on the development of cooperation on the ECE platform. Tauber, Kaiser and Schot saw the success of the Commission in its broad focus, which allowed the delegates to discuss a wide range of issues of inter-bloc cooperation.[10] The ECE archives in Geneva show that another factor enabling the Commission to contribute to the development of East-West ties was the successful depoliticization of its technical committees. Polish and Czechoslovak experts sought to exploit this aspect to maximize the import of Western know-how and facilitate its further dissemination to other CMEA economies. The more specific the focus of the ECE body, the stronger the depoliticization of its work. For this reason, the East-West cooperation was particularly fruit-bearing in the context of specialized working groups and ad hoc meetings often established to solve a unique problem of international cooperation.[11] The vast potential of depoliticized ECE bodies increased the interest of socialist governments, which sought to use the Commission as the main platform for organizing new forms of inter-bloc cooperation. Consequently, strong protests from CMEA members were heard in such ECE committees, where the US tried to transfer their powers in organizing international cooperation to purely Western organizations.[12]

In addition to the wide range of depoliticized working groups and ad hoc meetings gathering an array of experts and know-how, the role of the ECE Secretariat proved to be crucial.[13] Wightman even considered the Secretariat, headed by Gunnar Myrdal, as one of the main instigators of inter-bloc rapprochement.[14] The ECE archives in Geneva in this regard show that the importance of the Secretariat stemmed, among others, from its function of “information pooling”, since it collected a wide range of statistical data and bulletins from all member states, which were then used by the individual governments to optimize their inter-bloc foreign policy.[15]

The UN archives in Geneva show that not only professional, but also personal contacts between the representatives of the Secretariat and individual delegates of ECE member states played a key role in the successful establishment of inter-bloc cooperation links, as a number of negotiations on potential East-West projects took place outside the official bodies of the Commission. For example, in the early 1950s, Myrdal invited representatives of both sides of the Iron Curtain to a private dinner at which the possibilities of developing interbloc trade were discussed in an informal setting. Similarly, Myrdal’s assistant Chossudovsky organized private meetings of CMEA and Western delegates in his office in the UN building. The friendly personal relationships strengthened in this way then led to a greater willingness to share know-how and join proposed projects.[16] Besides Myrdal and Chossudovsky, other members of the ECE Secretariat, including Melvin M. Fagen and Václav Kostelecký were among the main facilitators of East-West dialogue.[17] It is noteworthy that many of these secretaries, as their names suggest, came from the Eastern Europe and thus possessed unique aptitudes and capacities to establish links between the two blocs.

Although many of the previous studies (Wightman, Kladiva) focused mainly on the positive influence of the ECE on the development of inter-bloc trade, new archival findings indicate that the added value of the Commission also lay in its capacity to promote the organization of scientific-technical cooperation projects. In this respect too, the Secretariat was instrumental, as it assisted individual experts and entire scientific-research institutions from the Eastern Bloc in establishing contacts with their Western partners.[18] For example, Eastern European scientists from the Research and Experimental Institute of Materials and Building Constructions (Výzkumný a zkušební ústav hmot a konstrukcí stavebních) in 1949 used the assistance of the ECE Secretariat to mediate contacts with analogous organizations in the West.

However, as already indicated, the administrative office of the ECE not only acted as an executor of Eastern European requests, but proactively sought out new opportunities to develop inter-bloc trade. To this end, representatives of the various divisions of the ECE Secretariat travelled to individual member countries and, in negotiations with their economic representatives, mapped out opportunities to strengthen East-West ties. On this basis, for instance, as early as 1948 the Secretariat proposed new trade channels to optimize the Czechoslovak-Belgian commercial exchange and to restore Eastern European imports of Swedish steel.[19] It also organized bilateral meetings of Greek and CMEA trade delegations for the purpose of introducing additional items into reciprocal trade.[20]

Last but not least, it must be acknowledged that an important pull factor for the participation of the Eastern economies on the stage of the ECE was not only their interest in the development of inter-bloc ties, but also the opportunity to strengthen ties between the respective countries of the Eastern Bloc. During the early post-1947 era, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland in particular, and to some extent other socialist states, shared a number of challenges that they sought to jointly target within the ECE sessions and committees. CMEA representatives on the ECE platform thus addressed, for example, the possibilities of increasing credit supply, the introduction of new forms of multilateral trade negotiations, and the return of rolling stock seized by the Nazi regime during World War II.[21]

The ECE annual reports reveal that despite the positive contribution of the Commission to the development of the Eastern Bloc in the years 1947-1950, it must be admitted that many ECE bodies reached a deadlock due to the escalation of the Cold War in the early 1950s. A comparative analysis of ECE annual reports from the individual years of the late Stalin era points to the stagnant number of inter-bloc projects implemented through this platform especially in 1951 and 1952. One of the projects that was successfully negotiated at the beginning of the Cold War, but later postponed due to its escalation, was the construction of a common electricity grid, which was only realized in the Khrushchev era after the relaxation of the Western embargo policy.[22] Similarly, the Cold War climax made it impossible to complete the loans of hard currency negotiated by CMEA representatives within the Timber Committee.24

An important reason for the failure of many of the intended projects seems to be the counterproductive attitude of the US delegation, which often denounced the draft resolutions of the Eastern Bloc as political instruments of socialism. However, according to the ECE archives, many of these “socialist” proposals were purely technical and so the US position can be seen as an attempt to politicize inter-bloc cooperation on the ECE platform. By the end of the Stalin era, the process of politicization had progressed to the point where it was no longer confined to general sessions, but was also visible in selected committees such as the Committee on the Development of Trade or the Committee on Manpower.[23] However, it needs to be acknowledged that despite the stagnation in the development of inter-bloc cooperation on the ECE platform towards the end of the Stalin era, this organization continued to play the role of one of the main East-West mediators.

Czechoslovak Bridge over the Iron Curtain

In the early years of the Cold War, the Czechoslovak government and individual experts proved significantly more proactive in participating on the platform of cross-Curtain organizations than the representatives of other socialist states. This phenomenon was due to several factors. Czechoslovakia’s economy traditionally had strong links with Western European countries, and the drawing of the Iron Curtain was unable to break all these ties. Thus, during the Gottwald era (1948-1953), the Czechoslovak market remained dependent on Western imports of raw materials and technology. Moreover, the leadership of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (CPC) did not completely abandon the vision of Edvard Beneš and Jan Masaryk of Czechoslovakia as an “intermediary between the two emerging geopolitical blocs”. In this regard, the Czechoslovak government sought to transfer political-economic intel and scientific-technical know-how from the West to other socialist countries.[24] The role of the intermediary was made possible by Czechoslovakia’s existing ties to capitalist states and its strong diplomatic tradition.[25]

In addition, it needs to be emphasized that the further development of inter-bloc ties on the platform of international organizations was greatly facilitated thanks to the approach of the more liberal wings of the CPC leadership, including Vladimír Clementis and Rudolf Margolius, who positively evaluated the work of a number of technical bodies and urged a further deepening of Czechoslovak cooperation.[26] The pro-cooperative approach of the Clementis’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs was visible in 1949, when this department discussed the further participation in the work of the ECE and decided to continue sending delegates to 75% of the ECE bodies in which they had previously participated. Similar support for the further development of Czechoslovak inter-bloc cooperation was expressed by the Office of the Presidency of the Government (Úřad předsednictva vlády), which argued that a wide range of the orders of business of international economic platforms affected the immediate interests of the Czechoslovak economy and that it was therefore necessary for Czechoslovak delegates to participate in their work.[27]

The subsequent increase in the activities of the liberal branch of the CPC targeted mainly depoliticized technical bodies (sub-committees, working groups, ad hoc meetings) that offered a higher potential to develop constructive forms of cooperation. The constructive approach to developing cooperation through these platforms can be demonstrated by the composition of Czechoslovak delegations, which often consisted of scientists, engineers and other experts with practical technical know-how.30 In addition, these experts evolved from irregular and passive observers to proactive chairmen, vice-chairmen and other key members of individual organizations. Therefore, for example, in 1949 Antonín Svoboda acted as Chairman of the Technical Sub-Committee of the International Union of Railways, in 1950, Bohumil Sucharda was the only CMEA representative in the Executive Board of the IMF and in 1953, Josef Ullrich chaired the entire session of the ECE.[28]

Activities were pursued both in the field of inter-bloc trade as well as in the area of scientific-technical cooperation. In this regard, the approach of Czechoslovak delegations was twofold. While the participation in the IMF and general ECOSOC sessions focused on the formation of a suitable macro-level environment for the development of East-West cooperation, participation in more specialized technical bodies such as ECE committees, GATT working parties or selected organizations like the International Sugar Council often aimed at negotiating specific scientific-technical projects and emerging issues.[29] The advantage of the technical bodies was both their ability to pool a large number of experts, studies and data as well as their capacity to organize study tours, joint research projects and symposia, or to mediate inter-bloc contacts between individual enterprises and research institutes.[30]

On the other hand, it needs to be recognized that the participation in the more general plenary sessions and annual meetings continued to be mostly politicized and controlled by the Stalinist wings of the CPC. As ECE annual reports from the late Gottwald era show, Czechoslovak delegates were often the sole representatives of the Socialist Bloc in a number of international organizations, which led to the formation of their specific role as both the main mediators of know-how and key promoters of the communist ideology.[31] In the context of the latter, the Czechoslovak delegates frequently sought to pre-negotiate and formulate criticism of Western discriminatory measures with other CMEA governments. This concerned topics such as the US withdrawal of the most-favored-nation clause from Czechoslovakia, the politicization of GATT, and the US intervention against the provision of credits to socialist states in the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development.[32]

The politicized Czechoslovak approach may be represented by the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Sekaninová-Čakrtová, who in 1950 tried to get more Czechoslovak officials into the UN Secretariat for the very purpose of effectively criticizing Western policies and promoting the ideological goals of the CMEA.[33] Similarly, within the ECE Committee on the Development of Trade, Czechoslovak delegates at times merely attacked the existence of CoCom embargoes that prevented the free inter-bloc movement of goods and services.[34] This approach on the platform of the ECE was often coordinated with Poland, which, along with Czechoslovakia, was one of the most proactive socialist members of the Commission.[35] Similar criticism of Western discrimination was presented by the Czechoslovak delegates in the GATT, where attention was frequently drawn to US violations of its articles.[36] Within the IMF, Czechoslovak activities were also often politically motivated. This can be demonstrated by Czechoslovak efforts to exclude the Republic of China from participation or in its criticism of the Fund’s loan policy, through which Western powers allegedly interfered in the domestic affairs of recipient countries.[37]

On the other hand, it must be admitted that the process of politicization of the selected organizations was not always caused by the targeted efforts of the Czechoslovak government, whose representatives sometimes only plunged into the politicized milieu and under tight conditions failed to develop constructive forms of cooperation.[38] This development was particularly characteristic of the years 1951 and 1952, during which the Stalinist isolationist policy and the Western discriminatory measures reached their climax.[39]

At this point it is appropriate to devote closer attention to the Czechoslovak involvement in the Economic Commission for Europe (ECE), which proved to be one of the key platforms for the development of depoliticized East-West cooperation. The strategic position of the ECE in the system of Czechoslovak international ties can be seen in the relative abundance of secondary literature that was dedicated to this topic in the communist era. For example, Posejpalová-Kohoutová outlined the personnel composition and the role of Czechoslovak representatives in the ECE, and Kladiva analyzed the various developmental phases of Czechoslovak participation.[40] These pioneering analyses indicated the centrality of the Commission as the main platform for directing the development of inter-bloc economic and scientific-technical cooperation.

One of the pivotal questions to be answered is the reason for the ECE’s key role in the development of Czechoslovak inter-bloc cooperation. As early as the beginning of the 1950s, Tauber, in his research on the function of the ECE Committee on Agricultural Problems, identified a number of factors that made the ECE system of international cooperation of a strategic importance to the development of the Czechoslovak economy. Among these factors stood out the Commission’s ability to bring together both a range of leading government officials and top economic and technical experts. In addition, already in 1949, Tauber had observed the proactive approach of the ECE Secretariat, which was successful in seeking new ways to link the economies of the two geopolitical blocs.[41] Czechoslovakia also had a specific role within the ECE as an intermediary of transfers between the two sides of the Iron Curtain. This status of Czechoslovakia was often leveraged by the CPSU, which sought to gain access to information about the state of Western economies. Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs present this practice through the participation of the Czechoslovak delegate Brus in the IMF. The Soviet embassy in Prague requested Czechoslovakia to share documentation received from the Fund and tasked Brus to find answers to a list of questions presented to him by the CPSU leadership. These questions concerned issues of Western economic development, monetary policy, trade, loans and foreign currency reserves.[42]

The ECE was not a homogeneous entity and its constituent sub-bodies had different aptitudes for the development of East-West relations. During the years 1947-1953, the Czechoslovak delegation was particularly active in the Timber Committee, where it organized a conference of experts in Mariánské Lázně (Marienbad) and in the Inland Transport Committee, where its experts participated in negotiations within the Conference of Custom Experts and the European Timetable Conference.[43] As the ECE annual reports indicate, the Commission also became an important organization for the eastward dissemination of scientific-technical know-how in the energy sector. In the early 1950s, Czechoslovak experts actively participated in projects of the ECE Electric Power Committee, which carried out extensive studies comparing different methods of generating and transmitting electricity. Similarly, the Polish and Czechoslovak delegates positively evaluated the work of the ECE Committee on Industry and Materials, which provided a wide range of documents on the state of raw materials in Western Europe.[44]

In addition to active involvement in the work of select committees, the Czechoslovak experts tried to take advantage of the proactivity of the Secretariat, which can be demonstrated by the approach of Arnošt Tauber, Vice President of the ECE and representative of the Czechoslovak Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who urged it to implement a range of studies that would help develop East-West trade.48 Similar efforts were demonstrated by Zdeněk Rudiger of the Construction of Large Machinery enterprise, who, in cooperation with the ECE Secretariat, tried to negotiate a loan to cover Czechoslovak imports of Western technology.[45] At the end of 1948, the Czechoslovak delegation in the Scrap Panel requested the Secretariat to mediate negotiations of scrap deliveries from Western Europe.[46]

Similar requests for assistance in securing an export license for Belgian industrial diamonds were directed to the Executive Secretary Gunnar Myrdal in early 1953.[47] These findings clearly indicate the interest of the Czechoslovak government in exploiting the capacities of the Secretariat to develop inter-bloc trade.[48] In addition to the strengthening of East-West commercial exchange, the ECE Secretariat was also used by the Czechoslovak delegation to gain access to information on the state of Western economies. During 1948, the Secretariat provided Czechoslovak Woodworks (Československé závody dřevozpracující) with statistical data on the state of the Western European timber industry.[49] Similar assistance from the ECE was positively evaluated by Jan Tauber of the Agricultural Research Institutes (Výzkumné ústavy zemědělské), to whom the Secretariat in 1950 provided data on the development of the Western European agriculture.54

On the other hand, since the individual ECE committees and their secretariats were also actively seeking new forms of inter-bloc scientific-technical cooperation on their own initiative, they have also become an important collector and analyst of data of Eastern provenance.[50] In this context, the ECE required from Czechoslovakia a number of sensitive and sometimes classified data on the state of the Czechoslovak economy. The partial depoliticization of the ECE and the sustained interest of the CPC in developing inter-bloc cooperation occasionally made the sharing of this information possible even during the Gottwald era.[51] Therefore, Jan Tauber, in this case representing the International Institute for Cooperation in Agriculture and Silviculture (Ústav pro mezinárodní spolupráci v zemědělství a lesnictví), was able to share with the ECE data on the state of Czechoslovak agriculture, which enabled the Secretariat to carry complex inter-bloc research studies.[52] Data were also provided on other occasions, for example by the Czechoslovak timber industry for an ECE study on the rationalization of this sector.[53] The willingness to share sensitive data on the state of the Czechoslovak economy is a clear evidence of the ability of the ECE Secretariat/committees to depoliticize their work and thus create suitable conditions for the development of inter-bloc dialogue. This led to Czechoslovak active involvement in the work of the ECE, which questions Wightman’s theory about the passivity of socialist states in this organization.[54]

Another key “organization” in nurturing the international economic dialogue in the late Stalin era proved to be the GATT, through which the Czechoslovak delegation managed to direct the development of its trade with both the developed capitalist states and those of the Global South. There were a number of motives that led the Czechoslovak government to remain in this “organization” despite the cost of its gradual “Westernization”.

In the first place, it should be mentioned that it was only the GATT platform that proved able to provide largescale favorable custom duties under the most-favored-nation clause. In this context, archives of the Czechoslovak Ministry of Foreign Affairs show that this department in the early 1950s supported remaining in GATT as it was estimated that the membership allowed for annual savings of around 25-30 million Czechoslovak crowns.[55] Withdrawal from the GATT could lead to increased tariffs and additional spending of scarce hard currency to import technologies, wool, non-ferrous metals and other raw materials from the West.[56] Similar reasoning came from the Czechoslovak State Bank (Státní banka československá) and the Ministry of Finance, which argued that the fulfillment of the Czechoslovak export plan depended on the benefits of GATT membership.[57]

Furthermore, in 1950, a special government meeting discussed the possibility of withdrawing from international economic organizations. At this occasion it was decided that maintaining trade relations with GATT members was necessary and that it was therefore desirable to participate in the 1951 Torquay Round negotiations for new tariff concessions.[58] These considerations of the Czechoslovak government clearly demonstrate the ability to pragmatically evaluate and occasionally enforce the practical needs of the national economy over the political-ideological principles of the Eastern Bloc. On the other hand, it must be admitted that the long-term goal of the CPC leadership was to minimize participation in pro-Western international organizations, including GATT. For this reason, the Czechoslovak Ministry of Foreign Trade began to seek to negotiate new bilateral trade agreements that would secure favorable tariff concessions in case the further deterioration in the political situation would force Czechoslovakia to withdraw from the GATT. However, the escalation of the Cold War in the early 1950s severely limited the negotiating capacity of the Czechoslovak government, which was only successful in concluding new agreements with India and Brazil.[59]

Frequent obstacles to the conclusion of additional trade deals were the unresolved compensations for nationalization and increasing pressures from the US government. Moreover, although it must be admitted that the First Czechoslovak Republic (první republika, 1918-1938) concluded a number of agreements containing clauses on preferential tariff treatment, the possibility of their renewal after withdrawal from the GATT was uncertain.[60] It was also for these reasons that even the more Stalinist wings of the CPC decided to remain in the GATT, as this organization was the only one perceived to be able to tackle a number of specific barriers to the development of inter-bloc trade. Thus, in the matter of GATT membership, the practical needs of the economy prevailed over ideological pressures calling for accelerated autarky.

Another specific organization significantly contributing to the development of inter-bloc economic cooperation was the IMF. The strategic position of the Fund for the Czechoslovak economy is evidenced by the fact that the CPC decided to remain in it throughout the Gottwald era, even though there were many obstacles in promoting the socialist vision of inter-bloc cooperation. It was not until December 31, 1954 that the withdrawal from the IMF took place after political circumstances had escalated. As in the above analyzed case of the GATT, the decision to remain in the Fund during the climax of the Cold War was motivated by the practical needs of the Czechoslovak economy. The GATT and the IMF were seen as similar organizations in this respect, working together in a complementary way in promoting the development of inter-bloc trade.[61] A theoretical withdrawal from the IMF was considered only after the Torquay Round of trade negotiations, which would have provided further tariff concessions and thus reduced the dependence on benefits offered by the Fund.[62]

One of the key benefits of the IMF was its ability to optimize Czechoslovak foreign exchange policy. Minutes of meetings of the Zápotocký administration held in mid-1950 show that in the event of withdrawal from the IMF, the government would have had to enter into bilateral monetary agreements fixing the parity of the Czechoslovak crown. The ability to negotiate these treaties in favor of the Czechoslovak economy was questionable and it was therefore recommended to maintain the status quo for the time being.[63] As the reports of the Czechoslovak delegation to the IMF from the second half of 1952 show, the interest in remaining in the Fund was also based on the need to maintain trade relations with developing countries. A number of them, including Mexico and Bolivia, were not in the GATT, and reciprocal foreign exchange relations would not be secured after Czechoslovak withdrawal from the IMF.

The decision to remain in the Fund during the Gottwald era thus clearly demonstrated Czechoslovakia’s interest in developing trade with both the developed capitalist economies and the Global South. As Rutarová indicates, another motivation for remaining in the IMF was its ability to provide foreign currency loans. In this regard, in 1948 the Fund granted Czechoslovakia a loan of USD 6 million to cover the imports of raw materials and technology and to facilitate the repayment of the negative balance of payments with Brazil.[64] However, the limited scope of this loan and the impossibility of negotiating similar credits after the escalation of the Cold War suggest that this form of assistance was not one of the main motives for remaining in the IMF.

Despite limited depoliticization efforts, it must be admitted that, especially in the 1950s, Czechoslovak cooperation within the IMF became largely politicized and often limited to protests against the participation of the Republic of China, criticism of the Fund’s discriminatory lending policy towards socialist countries, and complaints against the support of the IMF for the militarization of the Western Bloc.[65] The politicization of interbloc dialogue of the Fund led to a reduction of Czechoslovak interest in its activities. The correspondence between the Embassy of the Czechoslovak Republic in Washington and the Prague office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs from the turn of the Stalin and Khrushchev eras shows that the cooling of inter-bloc relations followed by the politicization led to the withdrawal of Czechoslovak participation from the Fund’s Executive Board.

In addition to these major economic organizations directing mainly macroeconomic elements of Czechoslovak inter-bloc cooperation, there was also a number of more narrowly oriented platforms that have often stood outside the main focus of contemporary historiography. However, despite their previous marginalization, the archives of Czechoslovak industrial ministries, supplemented by the correspondence of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, demonstrate that narrowly profiled platforms such as the World Meteorological Organization, the International Council on Large Electric Systems, and the International Civil Aviation Organization were generally more depoliticized and thus often more successful in achieving tangible outputs of inter-bloc cooperation.[66] Czechoslovak participation in them was handled both through the government, as in the case of the ICAO, and through individual experts, as in the case of the American Chemical Society or the American Institute of Electrical Engineers.[67]

A frequent motive for participation in these organizations was the need to construct inter-bloc infrastructure, which was considered a prerequisite for developing trade relations with capitalist economies. In addition, these platforms offered a unique access to Western journals, studies, statistics, bulletins, and other know-how that was difficult to obtain through bilateral routes.[68]

Conclusion

The present article analyzed selected aspects of economic and scientific-technical cooperation between the two geopolitical blocs during the late Stalin era, covering the years 1947-1953. The main focus was on the role of selected international organizations on account of which a premise of their profound, yet in the secondary literature not yet fully appreciated, influence on the development of the East-West dialogue was formed. In particular, the United Nations and its Economic Commission for Europe were taken into the spotlight. In addition, limited space was devoted to the role of the International Monetary Fund and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which continued to provide fragile but enduring links between the opposing camps during the escalation of the Cold War in the early 1950s. The issue of East-West cooperation was viewed through a fresh lens provided by the United Nations Library & Archives Geneva, supplemented by selected archival material from GATT, ECOSOC and socialist governments. This novel approach to an age-old subject allowed us to re-evaluate our understanding of international cooperation during the Cold War.

There is no denying that the political-ideological frictions between the two blocs have been reflected in the work of international organizations. Even the technical sub-bodies of the ECE and ECOSOC have not avoided occasional deadlocks that have prevented constructive dialogue on the development of economic and scientifictechnical cooperation. On the western side of the Iron Curtain, the main instigator of the stalemate was the US, whose delegates tried to politicize selected UN platforms. On the other hand, it is necessary to admit a certain guilt of Czechoslovakia and Poland, which often remained the only representatives of the Eastern Bloc in supranational platforms and from this role, partly shaped by the Soviet pressure, also contributed to the gridlock in the development of East-West cooperation.

In spite of these negative aspects in the activities of East-West organizations, it must be admitted that their influence on the development of inter-bloc economic and scientific-technical cooperation in the late Stalin era was of greater importance than previous historiographical research has assumed. Not only the ECE, but also other UN bodies and international organizations formed a suitable ground for establishing an inter-bloc dialogue. The more specific the focus of the selected body of the organization, the higher the likelihood it had of delivering tangible outcomes in the field of East-West cooperation. Thus, IMF and ECE working groups and committees frequently served as venues for conducting studies, exchanging data on the state of national economies, negotiating trade agreements, reducing tariffs, and arranging cooperation in the construction of inter-bloc infrastructure. As the ECE archives revealed, an important determinant of the ability of the selected platforms to achieve practical targets of cross-Curtain cooperation was the approach of their secretariats, which were not subject to the same politicizing pressures as national governments.

The potential of the international organizations has not gone unnoticed by the Czechoslovak government and individual scientific-technical experts. Delegates seconded to Geneva, Paris and Washington did not only seek to promote the socialist ideology and facilitate the fulfillment of intra-bloc obligations, but also to pursue their own depoliticized vision of the optimal form of East-West cooperation. The will and need of Czechoslovak representatives to maintain active participation in selected organizations was largely due to the traditionally strong connection of the national scientific-technical base and economy to Western European markets. These links were not completely deconstructed in the early communist era, and the issues caused by the accelerated efforts to socialize the economy forced even the Stalinist wings of the CPC to support some development of cooperation in ECOSOC, GATT, IMF and selected ECE committees. These findings help to deconstruct several outdated narratives about the dysfunctionality of international organizations in the late Stalin era, about Czechoslovakia’s passivity to participate in their activities, and last but not least, about the image of the Cold War as a period of two independent and isolated blocs.

[1] Fava, Valentina. “Motor Vehicles vs Dollars: Selling Socialist Cars in Neutral Markets. Some Evidence from the ŠKODA Auto Case.” EUI Working Papers MPW No. 2007/36. European University Institute, 2007; Lagendijk, Vincent C. Electrifying Europe: The Power of Europe in the Construction of Electricity Networks. Amsterdam: Aksant, 2008; Christian, Michael, Sandrine Kott, et al., eds. Planning in Cold War Europe: Competition, Cooperation, Circulations (1950s-1970s). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2008.

[2] Kaplan, Karel. Československo v letech 1948-1953. Prague: SPN, 1991. Průcha, Václav. Hospodářské a sociální dějiny Československa 19181992: 2. díl. Období 1945-1992. Brno: Doplněk, 2009; United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/EP/99-118, SR.1-SR.8, SC.1, E/ECE/EP/1-48, GX 18/9/2/1, GX 18/9/2/41; GATT Archives Geneva. GATT/126.

[3] Kladiva, Jiří. Evropská hospodářská komise OSN. Prague: NADAS, 1988; Hulinský, Ilja. Organizácia Spojených národov a Československo. Bratislava: Pravda, 1988.

[4] Schipper, Frank. Driving Europe: building Europe on roads in the twentieth century. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, Eindhoven, 2008; Lagendijk, Vincent C. Electrifying Europe: the power of Europe in the construction of electricity networks. Aksant, Amsterdam, 2008. 5 United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/SR.7/1-25, ECE annual reports 1948–1952.

[5] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/TRANS/SC1/71, E/ECE/TRANS/242, E/ECE/333-344: 1959; National Archives. finding aid 1204, fond 953, inventory no. 29, signature 056.3, carton 33.

[6] Nykryn, Jaroslav. Hospodářské styky mezi socialistickými a kapitalistickými zeměmi Evropy. Prague: Academia, 1981; Lagendijk, Vincent C. Electrifying Europe: the power of Europe in the construction of electricity networks. Amsterdam: Aksant, 2008; Štiková, Radka, “Členství Československa v Mezinárodním měnovém fondu v období 1945–1954,” Mezinárodní vztahy 3, (2009): 74–91.

[7] Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MEO-O, 1945–1955, carton 106, Mezinárodní měnový fond, zprávy Ing. Suchardy z let 1949 až 1950.

[8] Posejpalová-Kohoutová, Olga. Evropská hospodářská komise OSN 1968-1969. Prague: ÚVTEI, 1969, 147–148; Kladiva, Jiří. Evropská hospodářská komise OSN. Prague: NADAS, 1982, 20–34.

[9] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ARR 1360/022, Myrdal Papers.

[10] Kaiser, Wolfram and Johan Schot. Writing the Rules for Europe: Experts, Cartels, and International Organizations. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, 246.

[11] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/TRANS/SC1/71, E/ECE/TRANS/242, E/ECE/333-344: 1959.

[12] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/TRANS/376-459.

[13] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/141-151, 1952, E/ECE/COAL, EP, HOU, 1947–1959; Lagendijk, Vincent C. Electrifying Europe: the power of Europe in the construction of electricity networks. Amsterdam: Aksant, 2008, 102–104.

[14] Wightman, David, “East-West Cooperation and the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe,” International Organization 11, no.

1 (1957): 1–12.

[15] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX/10/2/1/12, letters between Jan Tauber, Zdeněk Augenthaler and the Secretariat.

[16] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ARR 14/1360, box 91, correspondence between Kostelecký and Myrdal, 1950, GX/11/3/3.

[17] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. see for example ARR 14/1360, box 91.

[18] Wightman, David, “East-West Cooperation and the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe,” International Organization 11, no. 1 (1957): 1–12; Kladiva, Jiří. Evropská hospodářská komise OSN. Prague: NADAS, 1982.

[19] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ARR 1360/022, Myrdal Papers.

[20] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ARR 1360/033.

[21] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ARR 14/1360, box 138, GX/11/3/3, Letter from Rovny to Ciszweski, 1949.

[22] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/EP/1-48, E/ECE/EP/99-118, SR.1-SR.8, SC.1. 24 United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ARR 14/1360, box 138.

[23] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/SR.7/1-25, ECE Annual Report 1949, 1952.

[24] MZV České republiky: CLEMENTIS Vladimír. retrieved August 1, 2021, from

https://www.mzv.cz/jnp/cz/o_ministerstvu/organizacni_struktura/utvary_mzv/specializovany_archiv_mzv/kdo_byl_kdo/clementis_vladi mir.html; see also Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. fond Generální sekretariát 1945–1955, Pozůstalost V. Clementise, Dokumenty V. Clementise.

[25] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/EP/1-48, E/ECE/EP/49-90, E/ECE/TRANS/1-55, E/ECE/TRANS/146-204, SR.3.

[26] MZV České republiky: CLEMENTIS Vladimír. retrieved August 1, 2021, from

https://www.mzv.cz/jnp/cz/o_ministerstvu/organizacni_struktura/utvary_mzv/specializovany_archiv_mzv/kdo_byl_kdo/clementis_vladi mir.html; see also Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. fond Generální sekretariát 1945–1955, Pozůstalost V. Clementise, Dokumenty V. Clementise; National Archives. finding aid 1171, fond 1190, inventory no. 343, carton 282, inventory no. 355, carton 309.

[27] National Archives. finding aid 1286/01, fond 862, inventory no. 466, archival unit 4827-5494, carton 128, see for example Evropská hospodářská komise: Československá účast na zasedání výboru pro vnitrozemskou dopravu ve dnech 13–17. června 1949 v Ženevě. 30 United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/COAL, EP, HOU, 1947–1959, ECE annual reports 1948–1953.

[28] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/SR.8, ECE annual reports 1947–1952; IMF Archives. IMF Annual Report 1950. retrieved August 1, 2022, from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/ar/archive/pdf/ar1950.pdf.

[29] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ECE annual reports 1948–1953; Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MO-T, 1945–1955, carton 5; GATT Archives Geneva. CP.3/SR22-II/28, Third Session of the Contracting Parties, Summary Record of the Twenty-second Meeting.

[30] National Archives. finding aid 835, fond 936, inventory no. 796, carton 68, inventory no. 71, carton 52.

[31] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/113-115, ECE annual reports 1948–1952.

[32] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. reports of the 1949 and 1950 annual sessions; National Archives. finding aid 1204, fond 953, inventory no. 29, signature 056.3, carton 33.

[33] Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MO-O, 1945–1955, carton 59; National Archives. finding aid 1286/01, fond 862, inventory no. 579, archival unit 8.080-13.709, carton 928.

[34] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/STEEL/34-68.

[35] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. reports of the 1949 and 1950 annual sessions.

[36] Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MO-T, 1945–1955, carton 5.

[37] Chmela, L, “Přednáška generálního ředitele Národní banky československé Dr. L. Chmely v Československé národohospodářské společnosti,” Hospodář 4, vol. 11 (1949): 3; Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MEO-O, 1945–1955, carton 106.

[38] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ECE annual reports 1949–1952.

[39] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/SR.7/1-25.

[40] Posejpalová-Kohoutová, Olga. Evropská hospodářská komise OSN 1968-1969. Prague: ÚVTEI, 1969; Kladiva, Jiří. Evropská hospodářská komise OSN. Prague: NADAS, 1982.

[41] Tauber, Jan and O. Vidlák. Evropské zemědělství a Výbor pro zemědělské problémy při EHK. Československý ústav pro mezinárodní spolupráci v zemědělství a lesnictví, Prague, 1950.

[42] Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MEO-O, 1945–1955, carton 106, Mezinárodní měnový fond, 13.5.1953.

[43] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/TRANS/SC1/71, E/ECE/TRANS/242, E/ECE/333-344: 1959; National Archives. finding aid 1204, fond 953, inventory no. 29, signature 056.3, carton 33.

[44] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ECE annual reports 1950–1951.

[45] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX 18/9/1/47, GX 19/9/1/47.

[46] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX 18/9/2/1, GX 18/9/2/41.

[47] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ARR 1360/022, Myrdal Papers.

[48] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX 18/9/2/1, GX 18/9/2/41, see also ARR 1360/022.

[49] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX 14/4/5, GX 14/4/12, GX/10/2/1/12, GX/18/3/6/2, Timber exports from Germany. 54 Tauber, Jan and O. Vidlák. Evropské zemědělství a Výbor pro zemědělské problémy při EHK. Československý ústav pro mezinárodní spolupráci v zemědělství a lesnictví, Prague, 1950; United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX 14/4/5, GX 14/4/12, GX/10/2/1/12, letters between Jan Tauber, Zdeněk Augenthaler and the ECE Secretariat.

[50] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/EP/1-48, E/ECE/EP/99-118, SR.1-SR.8, SC.1.

[51] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX 14/4/5, GX 14/4/12.

[52] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX 14/4/5, GX 14/4/12, GX/10/2/1/12, letters between Jan Tauber, Zdeněk Augenthaler and the ECE Secretariat.

[53] United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX/18/3/7/2, Timber consumption – Czechoslovakia.

[54] Wightman, David, “East-West Cooperation and the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe,” International Organization 11, no. 1 (1957): 1–12; Kaiser, Wolfram and Johan Schot. Writing the Rules for Europe: Experts, Cartels, and International Organizations. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, 163.

[55] Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MO-T, 1945–1955, carton 5.

[56] Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MO-T, 1945–1955, carton 5.

[57] Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MEO-O, 1945–1955, carton 106.

[58] Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MEO-O, 1945–1955, carton 106.

[59] Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MO-T, 1945–1955, carton 5.

[60] Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MO-T, 1945–1955, carton 5; GATT Archives Geneva. CP.3/SR22-II/28, Third Session of the Contracting Parties, Summary Record of the Twenty-second Meeting.

[61] Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MEO-O, 1945–1955, carton 106.

[62] Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MEO-O, 1945–1955, carton 106.

[63] Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MEO-O, 1945–1955, carton 106, Zápis z porady o členství ČSR v Mezinárodním měnovém fondu a Mezinárodní bance pro obnovu a rozvoj v souvislosti s účastí na Mezinárodní dohodě o obchodu a clech.

[64] Rutarová, Radka. Založení Bretton-woodských institucí a počátek jejich činnosti z pohledu ČSR (1944 – 1954). Master’s Thesis, Charles University, Prague, 2002, 100.

[65] Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MEO-O, 1945–1955, carton 106.

[66] National Archives. finding aid 1204, fond 953, inventory no. 29, signature 056.3, carton 33.

[67] National Archives. finding aid 1204, fond 953, inventory no. 29, signature 056.3, carton 33, Usnesení 201. schůze vlády, konané dne 22. července 1952.

[68] National Archives. fond VM SÚP, archival unit 491-1173, 91.

Bibliography:

-

- Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. fond Generální sekretariát 1945–1955, Pozůstalost V.

Clementise.

2. Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MEO-O, 1945–1955, carton 106.

3. Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MO-O, 1945–1955, carton 59.

4. Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. MO-T, 1945–1955, carton 5.

5. Chmela, L, “Přednáška generálního ředitele Národní banky československé Dr. L. Chmely v Československé národohospodářské společnosti,” Hospodář 4, vol. 11 (1949).

6. Christian, Michael, Sandrine Kott, et al., eds. Planning in Cold War Europe: Competition, Cooperation, Circulations (1950s-1970s). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2008.

7. Dejmek, Jindřich. Diplomacie Československa. Díl II., Biografický slovník československých diplomatů (1918-1992). Prague: Academia, 2013.

8. Fava, Valentina. “Motor Vehicles vs Dollars: Selling Socialist Cars in Neutral Markets. Some Evidence from the ŠKODA Auto Case.” EUI Working Papers MPW No. 2007/36. European University Institute, 2007.

9. GATT Archives Geneva. CP.3/SR22-II/28.

10. GATT Archives Geneva. GATT/126

11. Hulinský, Ilja. Organizácia Spojených národov a Československo. Bratislava: Pravda, 1988.

12. IMF Archives. IMF Annual Report 1950. retrieved August 1, 2022, from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/ar/archive/pdf/ar1950.pdf.

13. Kaiser, Wolfram and Johan Schot. Writing the Rules for Europe: Experts, Cartels, and International Organizations. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

14. Kaplan, Karel. Československo v letech 1948-1953. Prague: SPN, 1991.

15. Kladiva, Jiří. Evropská hospodářská komise OSN. Prague: NADAS, 1982.

16. Lagendijk, Vincent C. Electrifying Europe: the power of Europe in the construction of electricity networks. Amsterdam: Aksant, 2008.

17. Ministerstvo zahraničních věcí České republiky: TAUBER Arnošt. retrieved August 1, 2022, from https://www.mzv.cz/jnp/cz/o_ministerstvu/organizacni_struktura/utvary_mzv/specializovany_archiv_mzv/kdo _byl_kdo/tauber_arnost.html.

18. MZV České republiky: CLEMENTIS Vladimír. retrieved August 1, 2021, from

https://www.mzv.cz/jnp/cz/o_ministerstvu/organizacni_struktura/utvary_mzv/specializovany_archiv_mzv/kdo _byl_kdo/clementis_vladimir.html.

19. National Archives. finding aid 1171, fond 1190, inventory no. 343, carton 282.

20. National Archives. finding aid 1171, fond 1190, inventory no. 355, carton 309.

21. National Archives. finding aid 1204, fond 953, inventory no. 29, signature 056.3, carton 33.

22. National Archives. finding aid 1286/01, fond 862, inventory no. 466, archival unit 4827-5494, carton 128.

23. National Archives. finding aid 1286/01, fond 862, inventory no. 579, archival unit 8.080-13.709, carton 928.

24. National Archives. finding aid 835, fond 936, inventory no. 71, carton 52.

25. National Archives. finding aid 835, fond 936, inventory no. 796, carton 68.

26. National Archives. fond VM SÚP, archival unit 491-1173, 91.

27. Nykryn, Jaroslav. Hospodářské styky mezi socialistickými a kapitalistickými zeměmi Evropy. Prague: Academia, 1981.

28. Posejpalová-Kohoutová, Olga. Evropská hospodářská komise OSN 1968-1969. Prague: ÚVTEI, 1969.

29. Průcha, Václav. Hospodářské a sociální dějiny Československa 1918-1992: 2. díl. Období 1945-1992. Brno: Doplněk, 2009.

30. Rutarová, Radka. Založení Bretton-woodských institucí a počátek jejich činnosti z pohledu ČSR (1944 – 1954). Master’s Thesis, Charles University, Prague, 2002.

31. Schipper, Frank. Driving Europe: building Europe on roads in the twentieth century. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, Eindhoven, 2008.

32. Štiková, Radka, “Členství Československa v Mezinárodním měnovém fondu v období 1945–1954,” Mezinárodní vztahy 3, (2009).

33. Tauber, Jan and O. Vidlák. Evropské zemědělství a Výbor pro zemědělské problémy při EHK.

Československý ústav pro mezinárodní spolupráci v zemědělství a lesnictví, Prague, 1950.

34. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ARR 1360/022.

35. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ARR 1360/033.

36. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ARR 14/1360, box 138.

37. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ARR 14/1360, box 91.

38. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/113-115. 39. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/141-151.

40. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/333-344.

41. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/COAL, EP, HOU, 1947-1959.

42. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/EP/1-118.

43. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/SR.7/1-25.

44. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/STEEL/34-68.

45. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/TRANS/146-204.

46. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/TRANS/1-55.

47. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/TRANS/242.

48. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/TRANS/376-459.

49. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. E/ECE/TRANS/SC1/71.

50. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. ECE annual reports 1947-1953.

51. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX 14/4/12.

52. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX 14/4/5.

53. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX 18/9/1/47.

54. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX 18/9/2/1.

55. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX 18/9/2/41.

56. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX 19/9/1/47.

57. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX/10/2/1/12.

58. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX/11/3/3.

59. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX/18/3/6/2.

60. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. GX/18/3/7/2.

61. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. reports of the 1949 and 1950 annual sessions.

62. United Nations Library & Archives Geneva. SR.1-SR.8, SC.1.

63. Wightman, David, “East-West Cooperation and the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe,” International Organization 11, no. 1 (1957): 1–12.